Q4 2024 Portfolio Update

Note: Only two weeks until the release of “Buffett And Munger Unscripted”! Preorder a copy today to ensure that you’ll receive it as soon as possible.

The past two years have been favorable for TSOH Investment Research, with +35.1% returns in 2023 followed by +21.3% returns in 2024. (As a reminder, this accounts for ~100% of my family’s investable assets, i.e. everything to my name except cash in a checking account for living expenses.) While that’s an encouraging outcome after a difficult 2022, my boat hasn’t been alone in this rising tide - a fact made evident by a recent WSJ headline: “Stocks Cap Best Two Years in a Quarter-Century”. In addition, while the overall returns have been satisfactory, I’ve made my fair share of mistakes that prevented better results (for example, see Spotify and Comcast / Liberty Broadband).

Among the companies I follow, Mr. Market has shown growing enthusiasm for a certain group: he has been willing to pay a larger premium for companies with certain characteristics (long-term organic growth prospects and clear business stability), while shying away from those with less growth and / or certainty. I see this as a continuation of the “crossroads” that I wrote about in July 2024. It presents an interesting question for the long-term investor with a “go where the value is” mandate to answer: where is the breaking point?

Here’s an example that’s close to home for TSOH: Netflix. I first purchased the stock in January 2022, with further buying in April 2022. At the time of the second purchase, its enterprise value was roughly $100 billion - a mid-teens EV/EBIT multiple on my estimates, and with a belief that the denominator had plenty of growth coming in the years ahead. (As I wrote in “This Is When It All Matters”, “I’m of the opinion that the current valuation is very attractive.”)

A lot has changed at Netflix subsequently, but let’s just focus on the valuation for today: at ~$881 per share, NFLX has climbed ~5x from the 2022 lows, with an enterprise value of nearly $400 billion. Over that time, the multiple has roughly doubled (~32x EV/EBIT on FY25e); that is inclusive of some latent revenue opportunities that have since been tapped, along with higher EBIT margins. Put simply, the current valuation is much more demanding than Mr. Market’s ask a few years ago. Relative to industry peers like Disney, I think it presents a difficult question: how do you measure opportunity costs across multiple - albeit connected - variables (expected returns, quality, etc.)?

It’s interesting to consider how different groups of individuals might answer that question. If we were to examine a continuum of investors who were deciding what to do with NFLX stock over the past three years, one extreme would be “Never Sell” investors. They see Netflix as the long-term winner in global VOD / streaming, and they are unwilling to compromise on quality / certainty to own a company with a lower headline valuation. They’ve selected a similar approach to the one espoused by Charlie Munger: “Psychologically, I don’t mind holding a company I like and admire and trust and know will be stronger than now after many years. And if the valuation gets a little silly, I just ignore it. So, I own assets that I would never buy at their current prices but I am quite comfortable holding them… I cannot defend it in terms of logic… This is the way I do it; it keeps me more comfortable to do it this way.”

At the other end of the range are investors practicing a purer form of value investing: in theory, they wake up each morning, update their forward return calculations for the group of companies that they follow, and then reallocate their portfolios accordingly. It’s an approach with a certain intellectually honest – by definition, if “A” was up ~2% today, and “B” was down ~2% today, all else equal, you would like to allocate more to “B” than to “A” going forward.

Both approaches have their pros and cons. On the latter approach, here’s one of the trade-offs: it’s a near certainty you’ll never truly own anything in size. As NFLX moves higher, your approach will constantly push you to chip away at the position to reallocate elsewhere. This isn’t necessarily a good thing or a bad thing, but it is a choice: if you want to own stocks for the long-term, presumably because you think there are certain benefits associated with doing so, it’s very tough to marry that with an “expected returns” first approach. (Over the past 10-15 years, media investors in the second bucket sold / didn’t own Netflix, leaving them to choose among a list of “cheap” traditional media stocks; that hasn’t worked well, as I’ve seen with Disney.)

Personally, I lean towards the approach exercised in the first bucket; that said, as my recent actions with Netflix have shown, I still appreciate the inherent logic that informs the approach of bucket number two. I reside somewhere in between those two ends of the spectrum: I am willing to trim / sell as prices reflect more demanding expectations, but with a governor on decision-making that reflects a desire to maintain a long-term perspective.

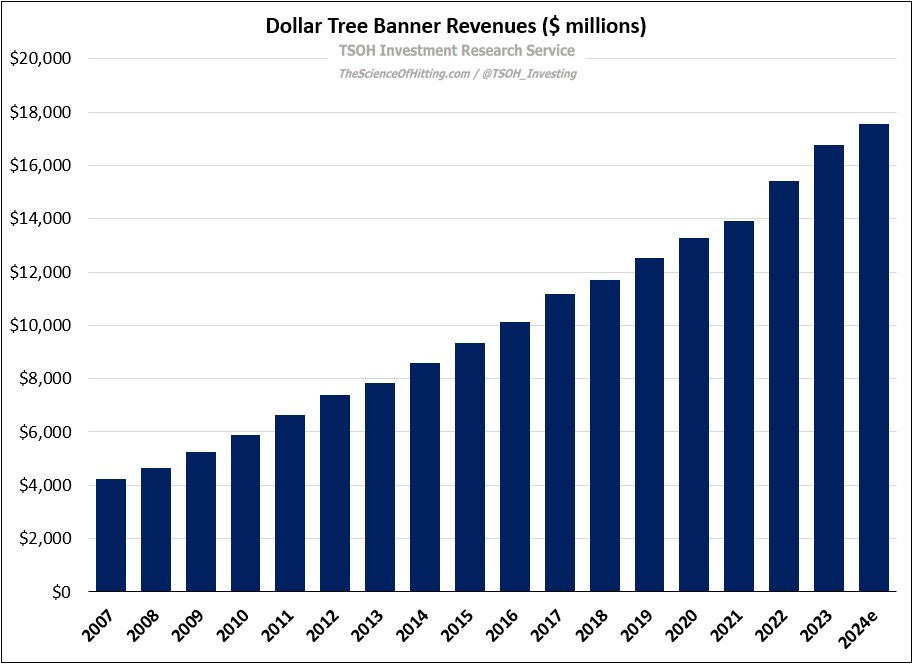

In practice, most notably at times when Mr. Market seems to be expressing more extreme views (positive or negative), that means a willingness to be open minded. Currently, this is most evident with Dollar Tree. The retailer certainly has its issues, and its long-term success isn’t as assured as it is for Netflix (in my opinion). At the same time, I’ve followed Dollar Tree for many years, and I think I have a good understanding of the purpose they serve for their core customers, how they got here, and where its future risks and opportunities lie. In my view, Dollar Tree’s valuation is very attractive, particularly as they capitalize on the strategic vision that they have outlined for each banner. I am being sufficiently compensated for taking incremental risk on certainty / quality relative to a stock like NFLX. If 2025 brings similar price action to 2024, then I will continue to lean into these types of names.

The point I’m hoping to make here was well captured in a note from Lewis Enterprises (link to the post, which you should take the time to read): “Making money was important to us, but it wasn’t the most important thing to us.”

Committing to an investment philosophy, particularly one that I write about publicly, can go awry if it then leads to a level of stubbornness that leaves me comfortable with sticking my head in the sand. While still staying true to my investment philosophy, I must also remember that the primary long-term objective is simple: to make money. Those ideas are not inconsistent with one another, but the desire for the former cannot outweigh the need for the latter.

In terms of the portfolio, that may mean certain positions appear at odds with one another, at least as conventionally defined (I’m not sure which style box you’d assign to a portfolio with DLTR, MSFT, NFLX, FEVR, and ALLY). While it lacks the purity of 100% commitment to a single bucket that is easier to explain (and sell), I think it’s a balanced approach that is likely to work well throughout market cycles. My objective is to generate attractive long-term returns; I will be rigid and flexible, as appropriate, in pursuit of that outcome.

Here’s the current TSOH portfolio, along with the updated returns.