"I Don't Defend This Logic"

Thoughts on #NeverSell

“Psychologically, I don’t mind holding a company I like and admire and trust and know will be stronger than now after many years. And if the valuation gets a little silly, I just ignore it. So, I own assets that I would never buy at their current prices but I am quite comfortable holding them… I cannot defend it in terms of logic. I don’t defend this logic. I just say this is the way I do it and it keeps me more comfortable to do it this way.”

That’s a quote from Charlie Munger, a man who once responded to the question “What one word accounts for your remarkable success in life?” with “I am rational.”

But where’s the rationality in continuing to hold a minority interest in a business that you would “never buy” at today’s price? For the intelligent investor, is there any defense for a valuation agnostic, “Never Sell” mindset?

To answer this question, I think it helps to look at a 2019 blog post from Akre Capital Management titled “The Art of (Not) Selling”. In the write-up, Chris Cerrone says that the Akre team views the sell decision similarly to Munger:

“Holding on means resisting the temptations to sell - and there are many. We tune out politics and macroeconomics. To the surprise of many, neither valuation nor price targets play a role in our sell decisions.”

Two of Cerrone’s reasons get to the core of the issue:

1) “Of the thousands of publicly traded companies, there are probably fewer than one hundred that meet our criteria, and opportunities to buy them at attractive prices are few and far between. Unlike average businesses that can be traded like-for-like on the basis of valuation alone, growing and competitively advantaged businesses are just too hard to replace.

His first point speaks to the need for prioritization. For Akre, a company must meet certain quality criteria before it can be added to their watch list – and if it doesn’t get past those filters, it is not a candidate for investment (full stop). For investors with a similar “quality first” mindset, like myself, wavering on those criteria to chase a (seemingly) cheap valuation can be a painful lesson to learn. In “Returns and Lessons Learned”, I wrote the following when discussing past mistakes like J.C. Penney, IBM, and Kraft Heinz:

“Why would I commit capital to the incumbents who were facing disruption as opposed to the innovators that were taking customers and market share? The answer is, all else equal, I’d naturally avoid the former for the latter. The problem was (and still is) that the companies in these buckets are far from equal on one key variable: valuation.

Ultimately, I let these valuation concerns become a justification for investing in the companies that faced a difficult hand, a reality that was clearly evident prior to my involvement (but one that I wrongly believed was being overstated). In the choice between a good business at a fair price and a (seemingly) fair business at a (seemingly) good price, I mistakenly chose the latter.

The takeaway, in my mind, is a slight tweak of my earlier conclusion: while a reasonable valuation is important to long-term investment success, it should be of secondary consideration in the research process. The first filter must be business quality. Unless it’s a high-quality business, it doesn’t matter if the stock trades at a discount to book value or a double digit FCF yield - for me, it’s a pass.”

The team at Akre views the funnel similarly. They’ve found the <10% of companies that meet their investment criteria (“fewer than one hundred… of the thousands of publicly traded companies”) and they have no interest in owning the thousands that did not make the cut, valuation be damned.

Of course, the trade-off with this approach is that the opportunity set is much smaller. What do you do if you’re struggling to find compelling value among those <100 companies? If you prioritize the first filter (business quality), then you may need to be less demanding at times on the second filter (valuation); in some cases, there’s no other option but to accept valuations that get “a little silly” (unless you’re willing to make meaningful changes in asset allocation, which is another idea that I’m not fond of when taken to extremes).

2) “The very best businesses tend to exceed expectations. What may seem like a high price today may be proven to be perfectly reasonable in hindsight.”

That’s an interesting comment. Who’s expectations are they specifically referring to? Do the very best businesses tend to exceed the market’s expectations, Akre’s expectations, or everybody’s expectations? The wording leads me to believe they’re referring to everybody, including Akre.

I’ve heard a variation of this idea (what it implies) in the past; it usually goes something like this: “It currently trades above my estimate of intrinsic value but I’m willing to give it a longer leash because it’s a great business.”

That comment incorrectly suggests that the asset’s characteristics - “a great business” - is not properly accounted for in the calculation. (Ben Graham made a similar point in “Security Analysis” as it related to “counting the same trick twice” for a good management team). The intrinsic value of an asset is based on all of the (discounted) cash flows that it will generate between now and Judgement Day. It doesn’t matter if it’s a “great business” – if you own it at a price in excess of an accurate estimate of intrinsic value, you are willingly accepting less than required rates of return or you don’t really believe in your own intrinsic value estimate (see “the very best businesses tend to exceed expectations”). I don’t want to speak for Munger, but I think it’s a reasonable guess that this is the reason why he “cannot defend it in terms of logic”.

Again, this is a man who has attributed much of his success in life to rationality. Why is he willing to continue to own these businesses without regard for their valuations? (To be fair, Munger at least has some guardrails by requiring the valuation to be “a little silly”. Akre, on the other hand, preaches a true “never sell based on valuation” approach to investing.)

I think the answer is that there is some logic to it all; Munger has selected an approach that he believes offers "the least bad option” for him (the kind of risk he’s willing to incur). My friend Bill Brewster likes to say traditional value investors understand the role of price mitigating left tail risks, while traditional growth investors understand the ability of the right tail to be longer than traditional value investors appreciate. “Never Sell”, when applied to the truly great companies, is the embodiment of this idea.

Like Munger, I’ve learned to live with valuations that are “a little silly” for the truly great companies (whether I’ve properly assessed their greatness is another question). I have more appreciation for right tails and Einstein’s “eighth wonder of the world” than I used to. In addition, as mentioned above, if I truly prioritize the first filter (business quality), there may be times where I have no other option but to compromise on the second filter. The alternative would be to sacrifice some amount of business quality in exchange for a better headline valuation (loosen the requirements of the first filter). But I’ve been down that road before – and it didn’t end well.

Conclusion

As someone who aspires to be a long-term owner of high-quality businesses, here’s what I’ve concluded: cutting off the right tail solely because the valuation appears “a little silly” is a bad idea. Over time, the opportunity cost is too high.

In those rare occasions where you find yourself invested in a great business with a long reinvestment runway being operated by honest and able managers, you should demand a similarly rare valuation to even consider parting ways with your equity interest. In terms of a multiple of current (or normalized) earnings or cash flows, it deserves something much higher than what the average business receives. (That’s another way of saying the companies experiencing this confluence of tailwinds are almost always underappreciated by the market.)

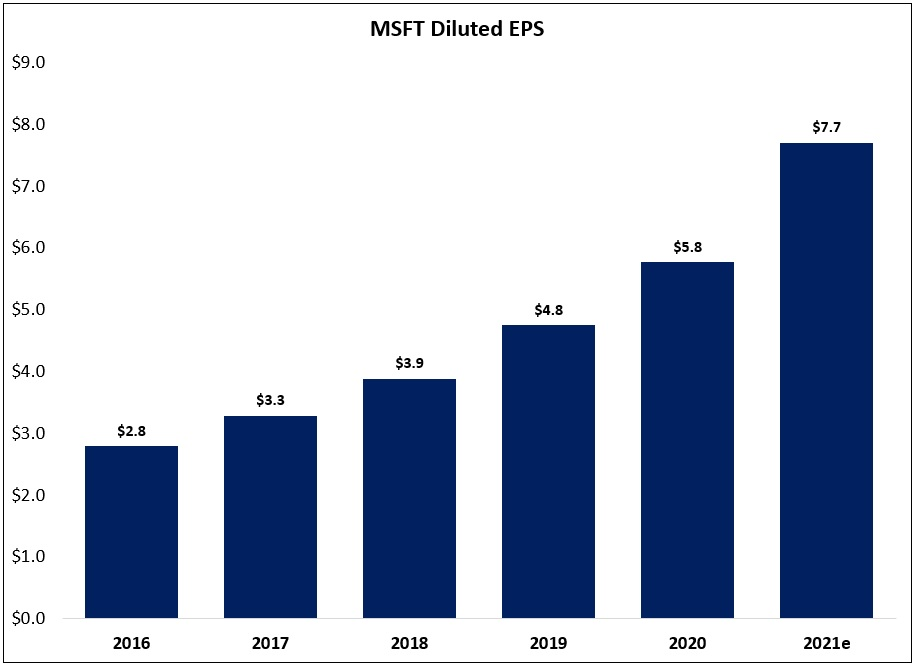

For me, Microsoft fits that description. It’s been a top holding in my portfolio for a decade. Did I think it was the best risk/reward opportunity available to me that entire time? Of course not. For one, I did not foresee much of what has happened over the past ten years. But what I thought I owned, especially after a few years of Satya Nadella’s leadership, was a wonderful business with a fortress balance sheet and a best-in-class management team that had the opportunity to grow at attractive rates for many years as they pursued markets with massive TAM’s. For me, that provided sufficient rationale for accepting “a little silliness” – and so far, it’s worked out well (both in terms of the business results and the stock price).

One final point here, which ties into the Microsoft example as well (Nadella): There’s a grey area where security analysis and faith begin to blur. I think that’s particularly true when you’re dealing with an all-star manager.

When you’re partnered with a truly one-of-a-kind leader like a Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, Bob Iger, or Mark Zuckerberg, and you have good reason to believe that they’ll be a steward of your capital for the next 10, 20, or 30 years, what’s that worth?

For example, let’s say it’s 1975 and a close friend tells you about a guy out in Omaha, Nebraska who absolutely crushed the markets for his LP’s when he ran a fund (1957 - 1969 gross returns of +29.5% p.a., compared to +7.4% p.a. for the Dow). You look into it and everything checks out - he’s a brilliant capital allocator, he’s honest, and (importantly) he’s young enough that he’ll probably be able to run this company of his, Berkshire Hathaway, for another 20, 30, or even 50 years.

What’s that worth in terms of price-to-book?* How do you quantify that?

That’s an extreme example, but it’s revealing: the sweet spot for #NeverSell is when you find the right person and / or a competitively advantaged business with room to reinvest and grow at the right time - most notably when the CEO is young and the company is small (that would be ideal, but it’s not a requirement). They are in a position to meaningfully exceed investor expectations for years or maybe even decades – because nobody has any basis for such seemingly absurd expectations (or at least not anything tangible that translates into next year’s earnings estimate or a five-year financial model). When you team up with leaders like Buffett, Bezos, Iger, or Zuck, they have a knack for doing things that nobody can foresee, but that ultimately generate massive amounts of shareholder value (See’s, GEICO, and BNSF for Buffett, AWS for Bezos, Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm for Iger, and Instagram for Zuckerberg, to pick a few examples).

What does that realization mean in terms of portfolio activity?

For me, it suggests that when you find that elusive combination of a truly great business and a truly great management team, you should do all that you can to hold on for dear life. That even includes ignoring the headline valuation when it becomes “a little silly”.

I can’t totally defend the logic of that conclusion. You could rightly argue that it lies somewhere in-between security analysis and faith.

But I’ve seen enough to know that it works - and that’s all that matters.

*The bottom chart shows the multiple of book value that you could have paid for Berkshire Hathaway Class A common stock at the end of 1975 to achieve different return CAGR’s over the next 45 years (through 12/31/2020).

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

Awesome post. When to sell has always been a question of mine. In hindsight biggest mistakes was I sold some FANGM too early and held on to crap too long.

Great read and thank you! What about trimming when a position has meaningfully exceeded your estimate of IV? The article talks about selling, which i'm inferring means to exit the position. Is it possible that you can reflect the valuation concerns and increased uncertainty through a smaller position size, whilst still having some exposure so you can still benefit in the event that the business surprises to the upside over time? There's a nice quote from Andrew Wellington (Lyrical Asset Mgmt): “There are fantastic risk/reward opportunities that you are willing to do at 3% of your portfolio that you might be unwilling to do at 10%."