Netflix: "This Is When It All Matters"

In June 2004, Netflix announced the first price hike for its standard DVD subscription service (+10%, from $19.95 per month to $21.99 per month).

But just five months later, Netflix reversed course.

As a result of a “changing competitive landscape” (a resurging Blockbuster, along with incursions by Walmart and Amazon), the company announced in November that the price would be lowered to $17.99 (they also introduced a lower-tier that allowed access to two DVD’s at a time for $11.99 a month). As noted in a 2005 CNN Money article, that was an ominous signal: “Price wars in tech are never a good sign.” In the 2004 shareholder letter (back when Netflix had ~2.6 million subscribers and ~$500 million in sales), management spent a fair amount of time discussing the competitive dynamics within the DVD market (“2004 was also a year in which we demonstrated our willingness to make hard choices — including lowering prices and deferring profitability — to protect our market leadership.”). But while Netflix’s streaming (SVOD) service wouldn’t launch for another three years, it was already clear by that point that management had their sights set on a bigger prize: “delivering a superior home entertainment experience”.

In the 2005 annual report, management wrote the following:

“We also anticipate the emergence of a significant downloading market once two primary hurdles are cleared: the availability of deep and compelling content and the technological challenge of getting the content from the Internet to the TV, where people want to watch it. We are absolutely focused on positioning Netflix to lead this market. It’s important to remember that downloading is just another way to deliver content, an alternative to the mail, or the local video store, or to cable, or to satellite delivery. The winners in downloading will be the companies that provide the best content and the best consumer experience, and that’s what we do best. With millions of online subscribers addicted to the Netflix Web site, we will have both a mass audience and the most compelling consumer experience in the market, which will give us critical advantages as we begin to offer downloading as a second delivery option.”

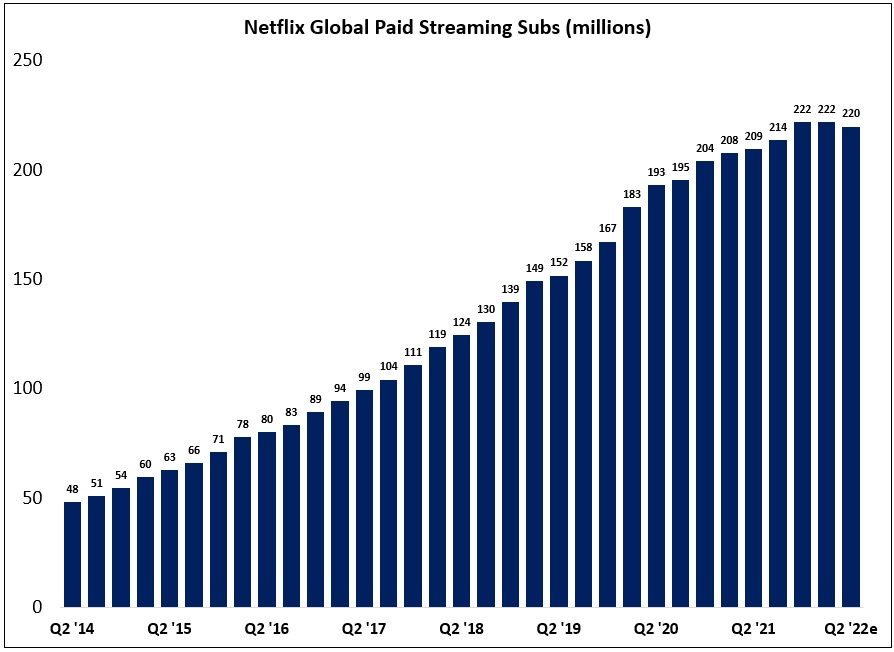

Jumping to the present, we can see that Netflix’s “absolute focus” on the streaming market has paid off. In Q1 FY22, the company reported that their customer base reached 222 million paid subscribers around the world, an increase of ~180% over the past five years (note that the company shut down its Russian service in Q1, which was a ~700k hit to the sub base).

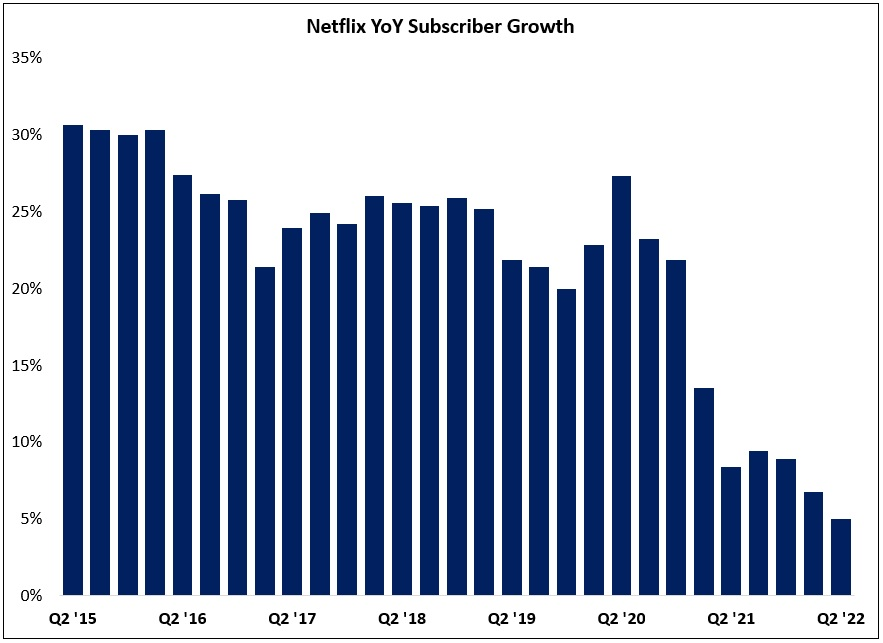

But as that second chart shows, the pace of subscriber growth has slowed meaningfully in the past 18 months; what was once assumed to be a temporary hangover from the pandemic now appears to be a larger issue. For context, here’s what I wrote about Netflix’s sub growth back in June 2021:

“One thing to consider as we think about the future is whether we’re resetting a base to grow off of (above 54 million net adds every two years) or if we’ve flatlined around that level. That’s not an unimportant question to answer, particularly as it relates to the TAM. Naturally, if you comp against a large and growing base, adding 27 million net subscribers every 12 months will have less of an impact on the growth rate than it did a few years earlier. This is bound to happen over time - you can’t add tens of millions of subs in perpetuity - but if it’s happening now, that’s a notable development. We’ll see if a meaningful increase in the number of content releases in 2H 2021 and into 2022 can provide investors with some reassurances on that front.”

In hindsight, the idea of leveling off at 25-30 million net adds per year looks overly optimistic (to say the least). The fact that CFO Spencer Neumann felt the need to reiterate that there will be revenue growth and paid net adds in 2022 is telling. This significant change in expectations has (rightly) led to consternation in the market, with NFLX down ~70% from its 2021 highs.

As always, my primary objective is to try and understand what this all means for a long-term investor / business owner; in this post, I will try and answer four key questions: (1) What just happened? (2) What are the long-term implications for Netflix? (3) What are the long-term implications for the industry? (4) Does this materially change the long-term investment thesis?

What Just Happened?

“Our revenue growth has slowed considerably as our results and forecast below show. Streaming is winning over linear, as we predicted, and Netflix titles are very popular globally. However, our relatively high household penetration - when including the large number of households sharing accounts - combined with competition, is creating revenue growth headwinds. The big COVID boost to streaming obscured the picture until recently.”

In the letter, the company pointed to four factors that are impacting subscriber growth: (1) the pace of TAM expansion, which is impacted by developments like the global adoption of smart TV’s and high-speed internet; (2) password sharing, which is a headwind to subscriber growth (I’ve long believed this is a good problem for Netflix over the long run, and an addressable one; the more important metric is revenues, which accounts for volumes and pricing); (3) competition, most notably in UCAN; and (4) macroeconomic factors.

While each of these points are valid, it’s quite a change in tone from just a few quarters ago (Q2 FY21: “It's still early days in pretty much every market around the world. We're ~20% penetrated in broadband homes and there's 800 million to 900 million broadband and / or pay TV households around the world outside China… We don't see why we can't be in all or most of those homes over time if we do our job.”). In addition, it’s worth noting that most of these factors (all besides #4?) have been knowable and have played a role in Netflix’s long-term subscriber growth for many years.

It would’ve been helpful if management gave investors concrete data that provided some support for these conclusions (for example, global connected TV sales for the past few years, which strikes me as a logical argument given the pull-forward in demand during the pandemic, supply chain issues, etc.). The most likely answer, in my opinion, is they’re not 100% sure what has led to an abrupt change in net adds either (maybe the COVID-hangover isn’t a one year event, with an ongoing impact on gross adds, along with increased churn as a result of competition and higher prices).

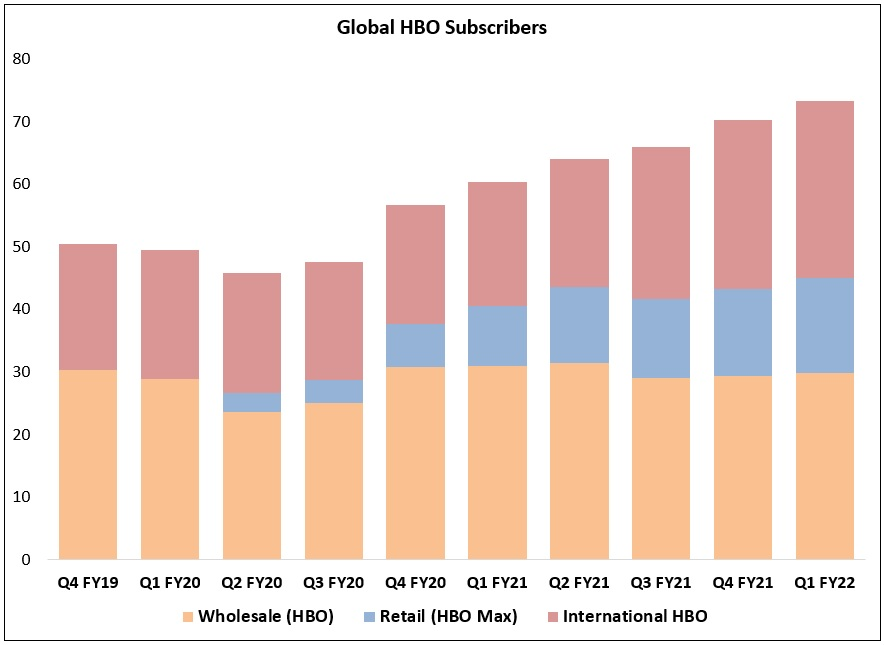

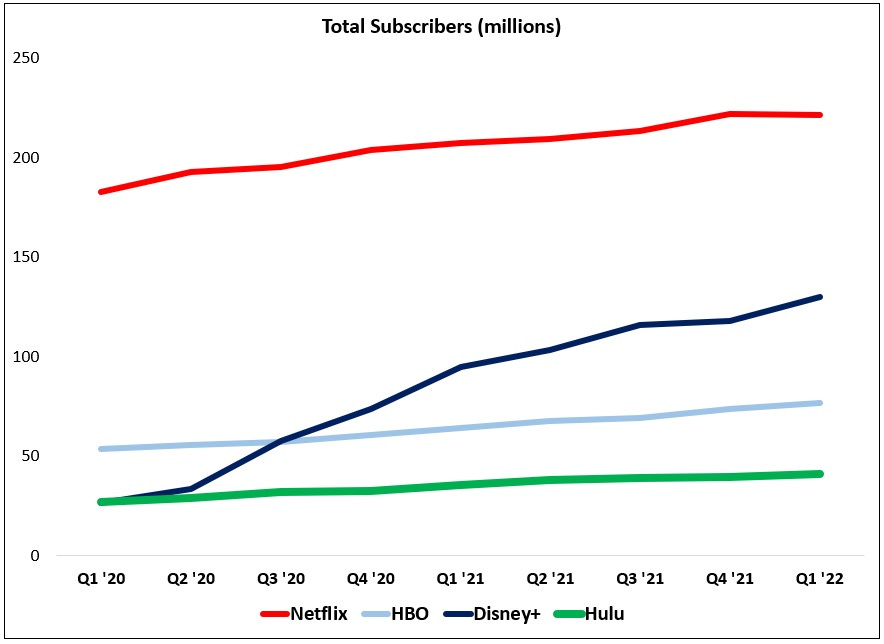

In summary, I honestly find these explanations to be somewhat confusing (which makes the seemingly rushed announcement on the call for an ad-supported tier that much more concerning). That said, I would note that competitors like WarnerMedia / HBO Max have also reported sluggish subscriber growth as of late, at least by my read (since the end of FY19, the HBO sub base has “only” increased by ~10 million net subs per year, with Netflix adding ~25 million net subs per year over the same period; at the end of Q1, Netflix’s sub base was still ~3x larger than HBO’s sub base).

Long-Term Implications for Netflix

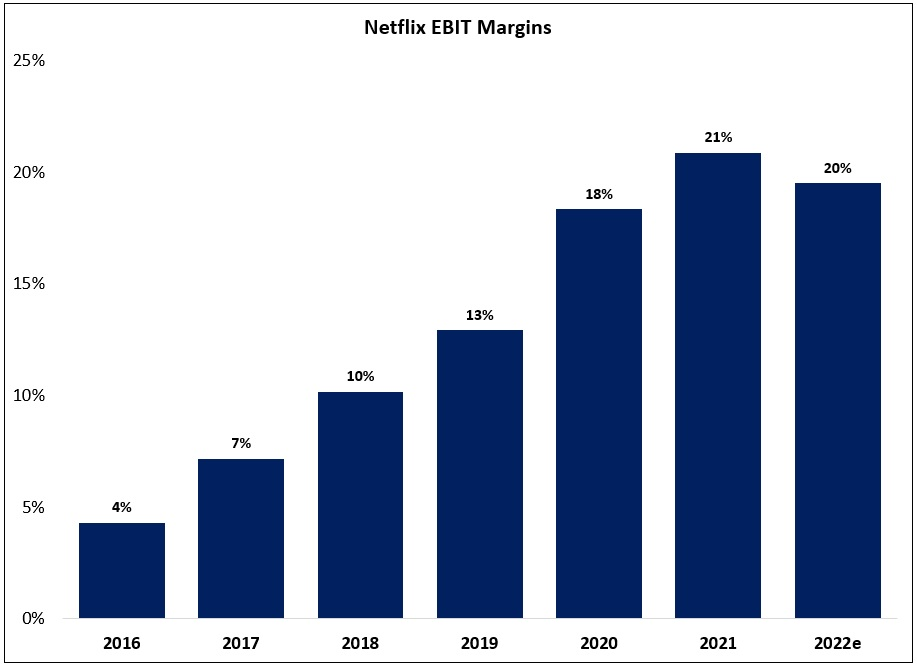

As I’ve discussed previously, Netflix management has guided to (and delivered on) ~300 basis points of annual EBIT margin expansion over the past few years. Coming into the Q1 print, it was already assumed that we’d take a breather in 2022, most notably due to currency headwinds and “over-earning” from 2019 – 2021 (when margins went up ~800 basis points).

Now, management has scrapped the margin guide; as disclosed in the Q1 letter, they expect EBIT margins over the next two years to be “at around 20%”. For analysts (like myself) who believed Netflix would have 25% - 30% EBIT margins within five years, this is a meaningful change in expectations, at least in the short-term (“Once we’ve re-accelerated revenue growth, we’re committed to steadily growing operating margins.”).

But on margins, much like the TAM, the question is whether we’re talking about a (major) bump in the road or a development that should lead us to question our prior long-term expectations. Based on the reaction to the results and the guidance, it’s clear Mr. Market has concluded that prior expectations are no longer valid. Personally, I’m less sure of that conclusion (I mean that in terms of the long-term revenue TAM, not subscriber TAM). That said, it’s difficult for me to square the 2022e results with my long-term expectations, so that clearly deserves some weight in my assessment (or at least until another logical explanation surfaces).

Long-Term Implications for Media

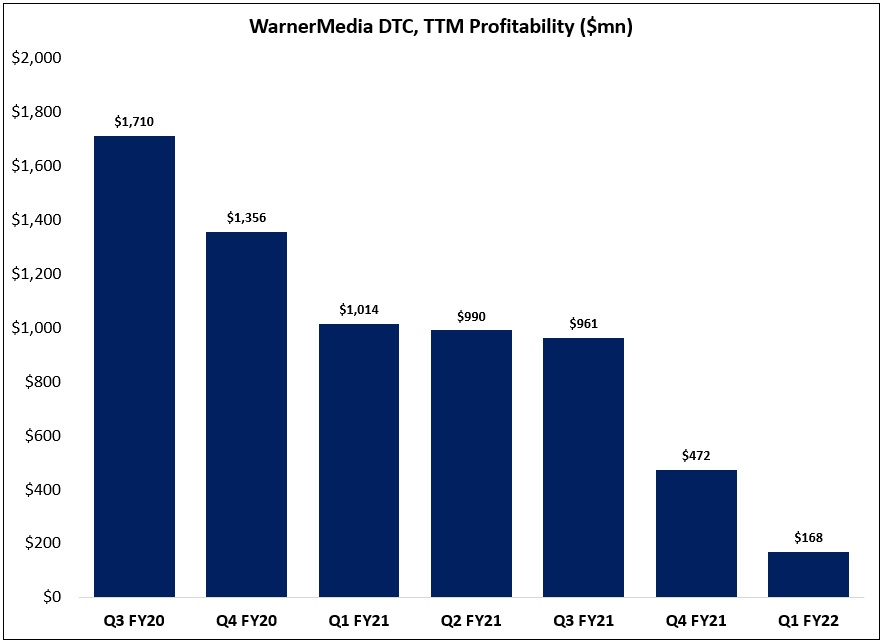

A key question that needs to be answered is whether this is a company-specific issue / blip or reflective of broader industry developments. We’re still waiting for some competitors (most notably Disney) to report their early calendar 2022 results, but my read from the data I’ve seen to date is that Netflix isn’t alone in its current struggles (as I’ve discussed previously, Disney faced its own DTC headwinds throughout FY21). That conclusion, if accurate, likely portends some tough decisions to be made at companies like NBCUniversal (Peacock) and Paramount Global (Paramount+). At a time when the long-term economics / TAM of streaming VOD is in question, will these companies reconsider the billions of dollars of annual content investments that they’ve committed to? In the case of WarnerMedia (HBO), one of the successful “new” entrants, TTM profitability in their DTC segment has declined by ~$1.5 billion in the past 18 months. As we look ahead, the key questions for these companies to consider are (1) How likely is long-term success?; (2) How much will it realistically cost?; and (3) How big is the prize? On each of those points, most notably #3, the outlook has worsened in the past 6-12 months. Said differently, the bar for accepting those sizable (and hopefully) short-term losses has risen.

This leaves people like Comcast CEO Brian Roberts with a difficult, albeit interesting, hand (his patience / dithering may ultimately be rewarded).

I continue to believe that there’s additional consolidation coming in the media industry (WarnerMedia / Discovery isn’t the end of the line), and a difficult period like this intensifies the calls for thoughtful strategic decision-making. (Maybe it’s worth reconsidering a return to licensing content to the highest bidder, a la Sony?) I think the clearest opportunity currently available is for Comcast to do a deal with Netflix. They can sell the Hulu stake to Disney (likely generating ~$15 billion in proceeds) and negotiate a long-term agreement with (sale to) Netflix that gives them global distribution for their high-quality content / IP while putting an end to the speculative investments at Peacock (one hurdle I see here is that Netflix is unlikely to want to take on the NBCU linear assets). The question is whether Roberts is willing to lessen his control over NBCU. If he’s open to an agreement, I think that would be hugely additive for both companies.

The Long-Term Netflix Thesis

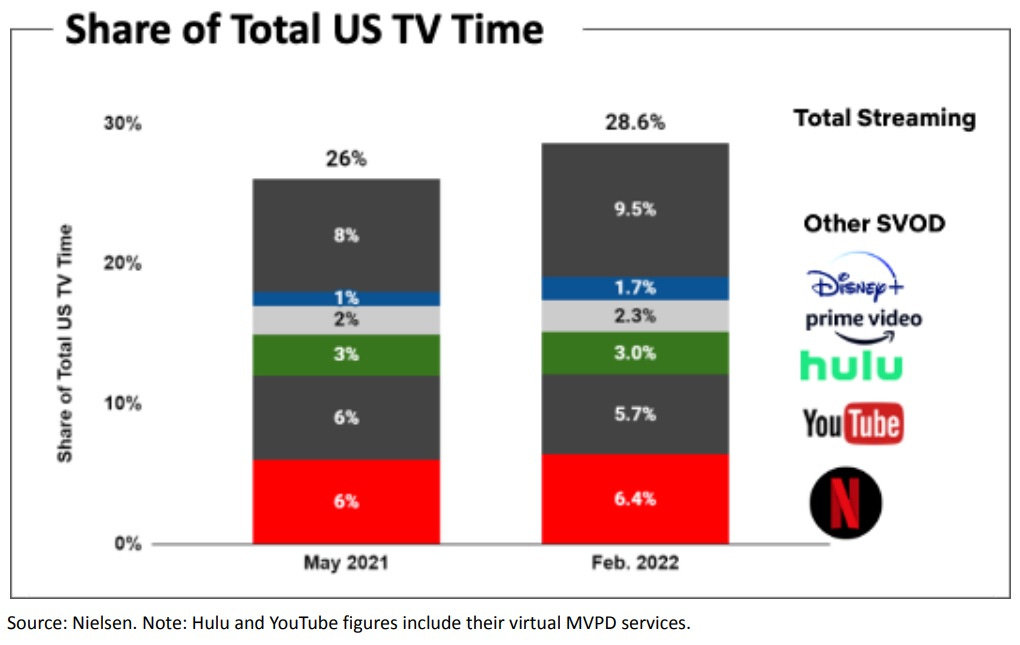

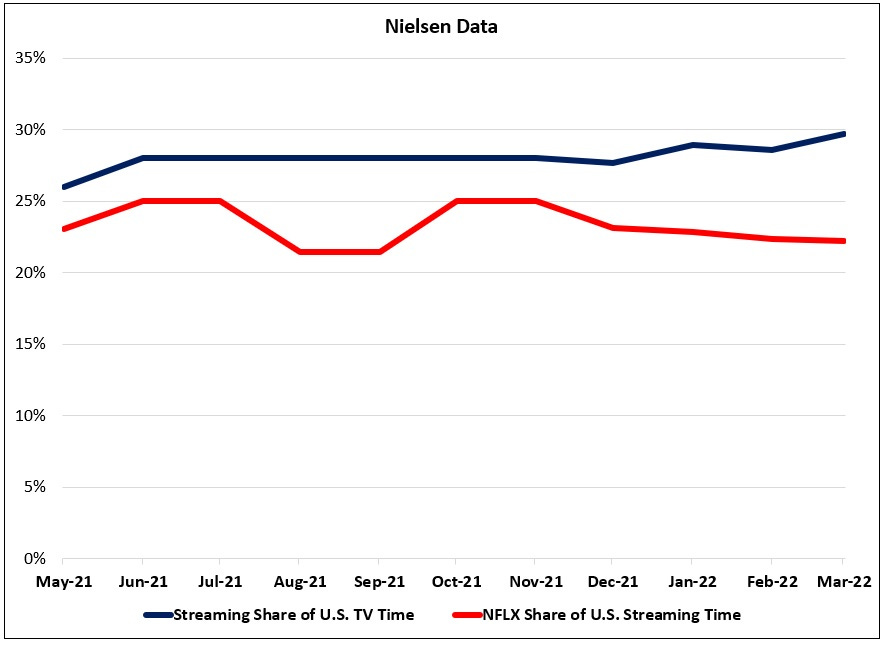

In the Q1 letter, management included a chart from Nielsen (reprinted below) that showed ~29% of all TV time in the U.S. in February was attributable to streaming. Personally, I view this as a timely reminder that we are still in the early innings of the shift to streaming (adjusted for the MVPD services, linear still accounts for ~75% of all U.S. TV time). Over the long run, I remain convinced that the overwhelming majority of households around the world will subscribe to services like Netflix, Disney+, HBO Max, etc. That may take another 10+ years to play out, but I think it’s fairly clear that this outcome will ultimately leave us with an industry leader in VOD with at least $60 billion in annual revenues (to put that in context, Disney’s U.S. linear TV business generated ~$20 billion in annual revenues before the 21CF deal).

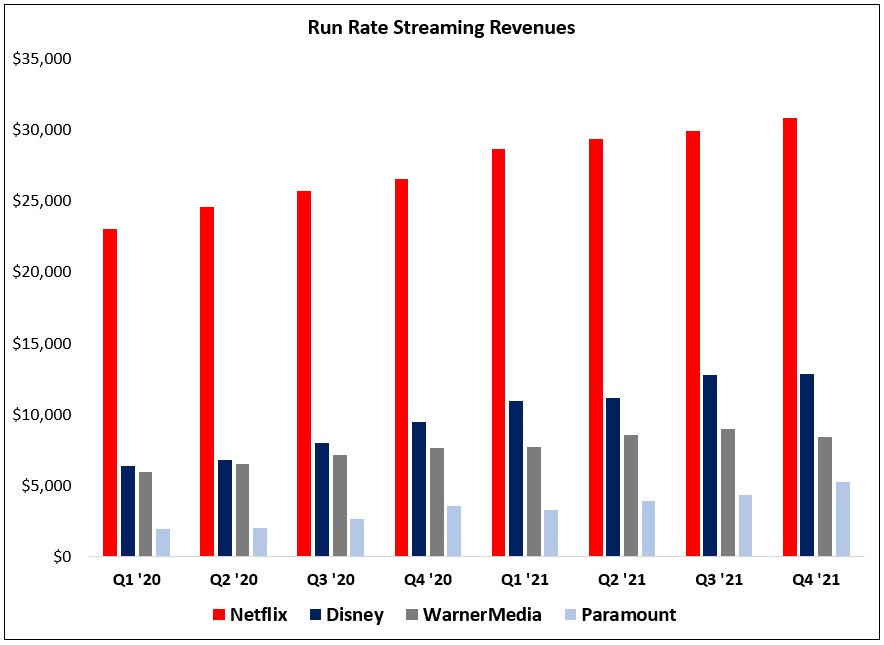

In my opinion, Netflix remains in the pole position. That said, long-term success will ultimately depend on their ability to leverage their competitive advantages – most notably a recurring DTC revenue base that is >2x larger than Disney’s, >3x larger than HBO’s, and multiples larger than the others. A big question in my mind is whether ability to spend will translate into effectiveness of spend (see the “best content” comment from the 2005 report). As an example, when Netflix spends heavily on a film like “The Adam Project” or “Red Notice”, how much long-term impact does that have on their brand / business in comparison to Disney spending on its next tentpole film from Marvel or Pixar? It’s safe to say that Netflix remains disadvantaged when viewed in that light, which may suggest they have a need for more shots on goal / higher spend to account for these shortcomings (a lack of must have IP). On the other hand, they’ve also cemented themselves as the clear industry leader, which makes them the most compelling partner for suppliers focused on global reach (comedians, sports leagues, etc.).

That conclusion suggests that Netflix should reassess some of their priorities, especially as they’ve shifted their views on an ad-supported tier. I think this development will likely lead Netflix to reconsider its presence in recurring / live programming like sports and news (co-CEO and Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos: “We expand our content verticals constantly”). The company has toyed with these ideas in the past, but I think it’s likely that this period will lead them to reconsider what kind of programming is “right” for Netflix long-term (for example, a deeper relationship with Formula 1 that builds on the huge success of “Drive to Survive”). It’s early days, but I expect a meaningful evolution in Netflix’s offering over the next five years.

Conclusion

During the Q&A session of the Q1 call, co-CEO Reed Hastings said the following about Netflix’s efforts to address password sharing: “When we were growing fast, it wasn't the high priority to work on.”

I think that’s an important comment for understanding Netflix generally. Over the past 10+ years, the company’s main priority was to spend as quickly as possible – on operations, content, etc. – to try and capture the huge opportunity presented from a rapidly expanding SVOD user base. Now that growth has slowed, the company is taking a step back to reassess and determine the best path forward. (“After churning out over 500 original programs last year, Netflix is looking to add fewer new titles, with a greater emphasis on quality, people familiar with the company’s strategy said. It is revamping production deals to limit its risk, and prioritizing programs with the biggest return, not the greatest reach, the people said. A key internal metric: the ratio of a program’s viewership to its budget.”) As they think through these decisions, I expect to see some notable changes that seemed unlikely - even unfathomable - just a few years ago (advertising, live content, etc.).

For me, a key part of any long-term investment is partnering with an honest and able management team; while this is a major bump in the road, I’m confident they’ll adjust and find a way to win in the years ahead. At the same time, I think legacy media companies will be forced to navigate these same challenges, with the kicker that they’ll be doing so from a much weaker position given a lack of global scale. (And as discussed earlier, that conclusion may sow the seeds for inorganic opportunities as well.)

At ~$216 per share, Netflix has a market cap of ~$98 billion. With run rate revenues of ~$32 billion and ~20% operating margins, the stock currently trades at ~15x EBIT. When viewed in the context of (what I continue to believe is) a massive long-term global opportunity, in combination with my belief that management will effectively navigate through this environment, I’m personally of the opinion that the current valuation is very attractive.

For that reason, I will be buying additional shares tomorrow. (As a side note, if you truly believe that Brian Roberts is open to a deal, CMCSA strikes me as a very attractive investment as well. I already own a sizable position in the company, but if I concluded that this was an increasingly likely outcome, there’s a good chance that I’d buy additional shares of CMCSA as well.)

I will send a portfolio update post after the close with the details.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

Marvellous yet again. Really admire your ability to cut through the numbers and lather on the qualitative perspective with the data in support.

Great post and thank you! How do you get comfortable with valuing the company on EBIT, given the disparity between earnings and cash flow (perhaps even less likely to resolve in the near term now given sub headwinds may force more content spend to maintain their market position)? I'm also still not sure where I sit on the idea that current content amortisation costs represent "maintenance" content spend and would love your take!