Netflix: Evolution

From “This Is When It All Matters” (April 2022): “Netflix should reassess some of their priorities, especially as they’ve shifted their views on an ad-supported tier. I think this development will likely lead Netflix to reconsider its presence in recurring / live programming like sports and news. The company has toyed with these ideas in the past, but I think it’s likely this period will lead them to reconsider what kind of programming is ‘right’ for Netflix long-term... I expect to see a meaningful evolution in Netflix’s offering over the next five years.”

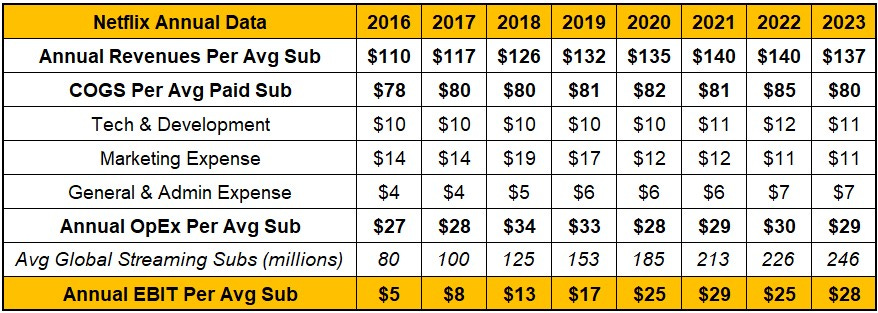

It’s interesting to consider how Netflix has been perceived by the investment community throughout the maturation of its streaming business over the past decade. For much of that period, the company was derided as a “subscriber story” with significant cash burn (for FY15 to FY19, cumulative negative free cash flow of ~$11 billion); some argued that this reflected a business with unattractive unit economics, which would eventually come home to roost.

In time, that analysis has proven off the mark; the primary reason has been significant ARM (average revenue per member) growth over the past five years, particularly in UCAN, which greatly contributed to the >2,000 basis point of EBIT margin improvement from FY16 to FY24e and ~$13 billion of total free cash flow in FY23 and FY24e. As shown below, that outcome has only been possible as a result of volumes and pricing; Netflix’s perception as largely a “subscriber story” completely missed the boat, and now stands in stark contrast to the legacy media companies who were late to the party.

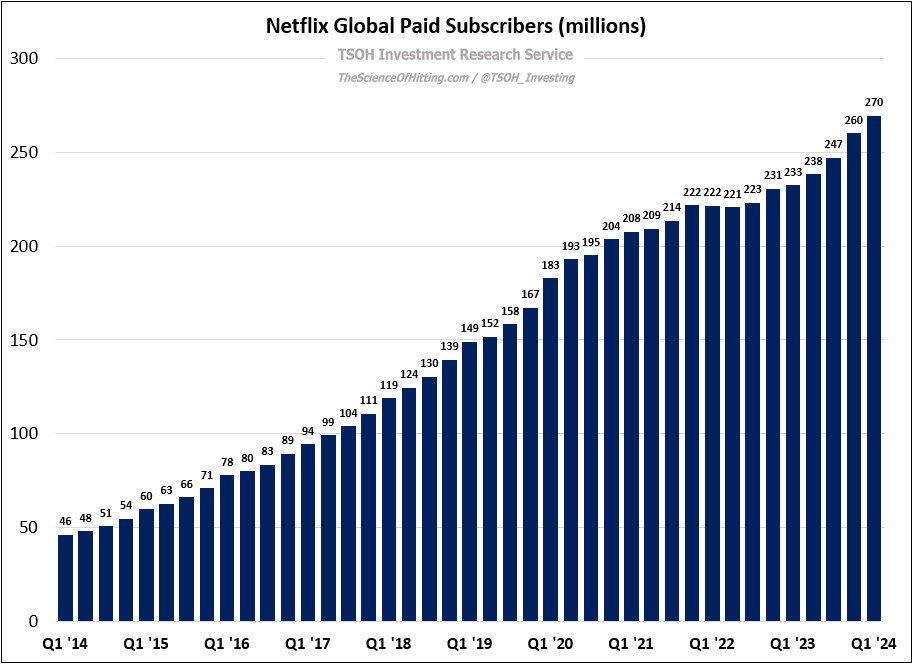

Netflix has now decided to stop reporting quarterly paid subs, replaced by periodic updates at major milestones. That decision is viewed by some as a sign of difficulties ahead, particularly as they lap the sizable tailwind from the password sharing crackdown. As an example, given that Netflix now has ~83 million paid subs in UCAN - a level that many analysts assumed that they’d never reach just 18-24 months ago - they are naturally closer to saturation on volumes in this market. (Paid subs were +16% YoY in Q1 FY24 to 270 million, the second highest TTM net adds in Netflix’s history; the record, at +41.5 million in Q2 FY20, reflected pandemic-related tailwinds in early 2020.)

On the Q1 FY24 call, co-CEO Greg Peters provided some explanation for this change: “We're going to continue to evolve; we have added things like advertising and our extra member feature, which aren't directly connected to the number of members. We've also evolved pricing and plans / tiers, with different price points across different countries. Those price points are going to become increasingly different… That simple math - the number of members times the monthly price (ARM) - is increasingly less accurate in capturing the state of the business… Ultimately, we think this is a better approach that reflects the evolution of the business, and it and is consistent with how we manage Netflix internally to engagement, revenue, and profit.”

As always, removing KPI’s understandably raises eyebrows. With that said, it’s important to think about what Peters is saying. As I’ve argued on numerous occasions over the past three years, it’s critical for investors to understand the financial implications of Netflix’s geographies being at different stages of their lifecycle. At one extreme we have UCAN, where the playbook is going according to plan (run rate revenues are now ~$17 billion).

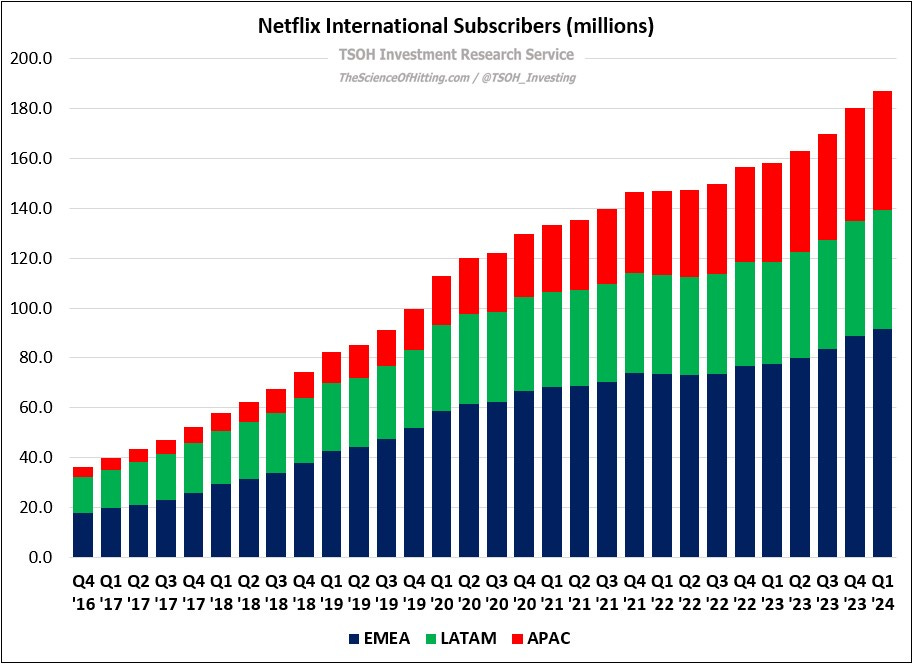

Then there’s International, where Netflix (generally speaking) remains at a much earlier stage of its development. As you can see below, ex-UCAN subs have increased by >5x since the end of FY16, to 187 million as of Q1 FY24. At the same time, ex-UCAN ARM’s have been flat to down in recent years.

These regions (collectively) are a ~$21 billion business for Netflix, a figure that has grown at a 19% annualized rate over the past five years. While many investors focus on media industry competitive dynamics in the United States, which is understandable given the size of the market and access to reliable data from Nielsen and others, this is a huge point of differentiation for Netflix: none of its peers have built an International DTC business anywhere close to this size, and I think they are very unlikely to do so in the years ahead. (The closest is Disney, with an International DTC business at ~$5 billion run rate.)

But it isn’t all roses for Netflix. Markets like India remain highly competitive (with most U.S. media companies throwing in the towel), and the round of International price cuts in early 2023 was a telling decision. This, in my view, likely played a role in their choice to stop reporting quarterly subs. Netflix has started to tweak its range of plan tiers, including the ad-supported (AVOD) tier and mobile-only plans. As we look to the next stage of Netflix’s evolution, particularly in International markets, I believe more changes are coming.

Here are two specific examples.