Peloton: McCarthy's Missteps

"More isn't necessarily better"

From “Peloton: Unwelcome Surprises” (October 2023): “The embodiment of that [‘anyone, anytime, anywhere’ brand] vision is the company’s digital app strategy; the declining number of app subscribers presents real questions about this vision. My view is that the best Peloton experience and the best business opportunity comes from the integration of its hardware and software. While it’s early days for the new marketing strategy and the digital app roll-out, I remain unconvinced that this is likely to drive material value for Peloton… I see a path for the company to generate consistent operating profits if they can narrowly focus on the economics of the core business…”

On Thursday, Peloton announced that CEO Barry McCarthy was leaving the company. The market greeted his arrival in February 2022 with optimism, pushing the stock to ~$40 per share. As he departs, the stock price has fallen more than 90% from the February 2022 highs, to ~$3.4 per share.

As you know, I’ve followed this story for the past two years. I’ve never owned Peloton (so far), but I think they’ve built a unique brand and business model in the home fitness market. At the same time, I’ve also argued they made some strategic errors, including during McCarthy’s tenure. Thursday’s news may prove to be an interesting turning point: by virtue of certain constraints, I think they may be forced to pursue a tighter strategy. As I’ll discuss today, it could lead to a step in the right direction for the business and the stock price.

McCarthy’s Missteps

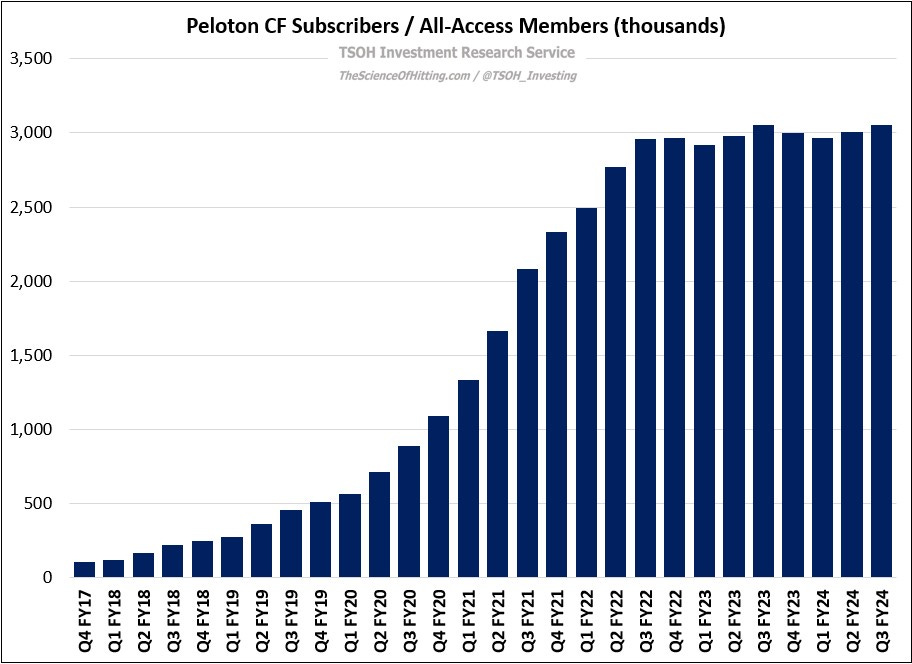

In “The Magic Happens On The Screen”, I discussed McCarthy’s strategic vision for Peloton. With the benefit of hindsight, I think the clearest disconnect between his vision and the results has been on CF subscribers: while that metric has continued (slowly) moving the right direction, to 3.06 million in Q3 FY24, I suspect the pace of sub growth has been more sluggish than he anticipated, particularly given the pricing strategies, business models (FaaS), and new retail channel partners like Amazon put into place during his tenure.

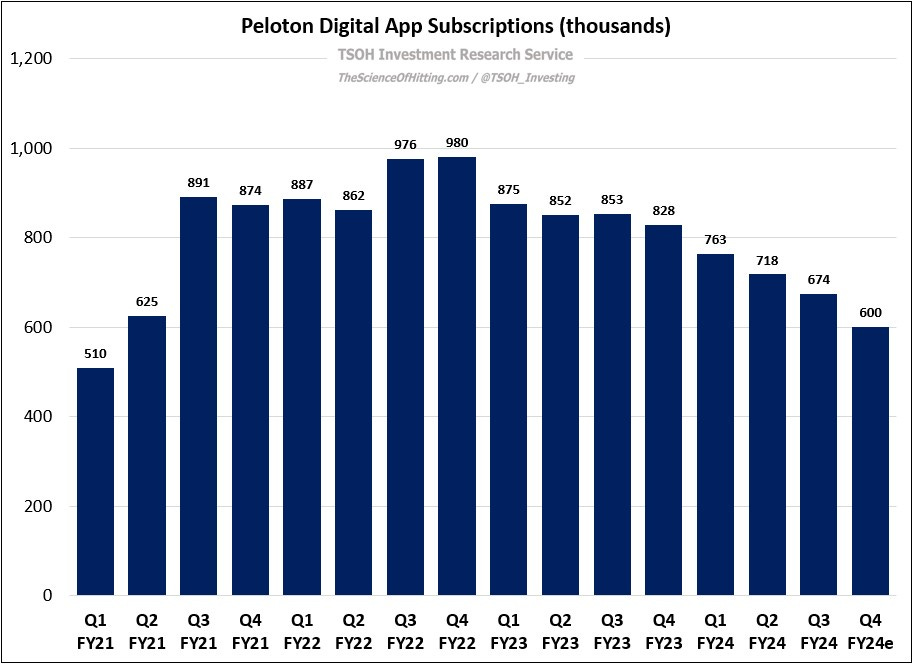

Another notable disappointment was on the digital app strategy (a way to engage with Peloton’s fitness / instructor content without owning their hardware). This comment, from McCarthy on the Q3 FY22 call, frames the expansive view that he had for this component of Peloton’s strategy:

“My goal is to become a global connected fitness platform with 100 million members… We need to widen the marketing funnel, and we’ll use the digital app to do that. It could be freemium or a straight subscription model, I’m not sure yet… Unaided brand awareness in the U.S. is 4%, so it’s the greatest app nobody’s ever heard of… Historically, the approach has been all-access first, digital later; I think that we need to change the order.”

The digital strategy was tweaked over time, but results have continued to disappoint: Peloton management expects to end FY24 with roughly 600,000 digital app subscribers, a decline of nearly 40% from the peak in Q4 FY22.

I have long believed that the digital app strategy was misguided and a likely distraction from the core business opportunity. Encouragingly, management stated in the Q3 FY24 letter that they are going to reduce media spend tied to the digital app; while they plan to continue investing in the product experience - “to improve product market fit” - I suspect the best use of their limited resources would be to refocus on the core. (Coddington on future marketing efforts: “We're going to focus on segments where we have the highest product market fit… By honing our messaging and targeting the right audiences, we’ll be much more efficient and be able to ultimately grow.”)

That alludes to a more fundamental question: what is Peloton? In my view, they sell high-end home fitness equipment (namely the bike). They compete and win when their hardware and software are packaged together as a single product. Peloton’s business model, as a result of its outsized per user revenues and gross profits, can support a level of investment competitors cannot match; they should be able to profitably offer a better product experience than other exercise equipment manufacturers. (One interesting example from the call was on Tread: runners can now experience the New York City Marathon course, including auto-incline functionality that matches the route’s gradient fluctuations.) That model – with its $44 monthly fee – isn’t for everybody. This, in my view, is where management misplayed their hand.

McCarthy and prior management were convinced Peloton should become a much larger business; given his prior experience at Netflix and Spotify, McCarthy may have argued Peloton needed to be much larger (a notable comment from his first shareholder letter was “as we play for scale”). In that pursuit, the brand was somewhat diluted and OpEx exploded, rising 4x from FY19 to FY22. A notable OpEx line item is R&D, which was $318 million in FY23 – nearly 6x higher than in FY19; its unclear to me what improvements were made to the core product offering as a result of that incremental spend.

Peloton’s recent experience reminds me of something that Charlie Munger once said to Chris Davis: “I was challenging Charlie on the idea that there’s a certain number of customers who would go to Costco if they didn’t have to be a member. I said, ‘The membership fee is 2% of revenues; if you raised prices 2%, you would still be lower cost than anybody else, yet you would have more customers. And because you would have more customers, you would have higher revenues. So, it would seem to me keeping customers out of the stores who would otherwise go is a mistake.’ Charlie’s answer was, ‘Think about who you’re keeping out. The cohort that won’t give their ID to be a member, they aren’t organized enough to come get their picture taken, or they can’t do the math to realize [the attractive customer value proposition]. That cohort will have ~100% of shoplifters, and it will have most of your small ticket purchases… It’s the intelligent loss of sales… You are young and you think that more is better, but more isn't necessarily better.’”