"It's Always About The People"

Note: I’ll be off next week for Christmas; I hope everybody has a happy holiday! As always, thank you for subscribing to the TSOH Investment Research service. With the three-year anniversary on the horizon (April 2024), I’m incredibly thankful for your ongoing support of this service.

Last week, Ken Langone was interviewed on CNBC’s Squawk Box. After discussing some of the great investments that he’s made over the past half century, including large positions in Eli Lilly (since 1977) and The Home Depot (since 1981), Langone was asked about the considerations that informed his investment decisions. He responded with the following: “To me, it’s simple: it’s always about the people. Nothing more, nothing less.”

In my early days as an investor, as I considered the relative importance of business quality and managerial quality on a potential investment, I leaned heavily towards the former. That perspective was partly informed by a misguided application of the famous quote from Warren Buffett’s 1980 shareholder letter: “With few exceptions, when a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for poor fundamental economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.” I took that pronouncement as permission to largely disregard any judgment about the people I was partnering with; a business of sufficient quality, the type that “any idiot can run”, was good enough for me.

Over time, I’ve come around to a different conclusion. Put simply, I think the quality of the business tends to bend towards the quality of the management team. As a CEO’s tenure lengthens, the combination of their long-term strategic vision and capital allocation decisions has a growing influence on the quality of what remains. (“After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for deploying more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.”) Through that lens, the starting assumption for an investor should be that most businesses are likely to be greatly impacted by the decision-making of a CEO who remains at the helm for an extended period. To see what this looks like in action, I want to discuss one of the most notable examples of this idea that I’ve seen over the past 10 - 15 years: Microsoft.

“Red Dog”

2011 was a banner year for Microsoft’s Server & Tools (S&T) segment, with revenues and operating income climbing +11% and +19%, respectively. And while CEO Steve Ballmer’s fiscal 2011 shareholder letter discussed notable industry changes underway – “the rate of businesses moving to the cloud continues to accelerate” – the internal view was somewhat less committed to the new way of doing things. As Satya Nadella recounted in “Hit Refresh”, the problem wasn’t that Microsoft was particularly late to the party or completely oblivious to what was happening. (“Not long after Ray Ozzie arrived at Microsoft in 2005, he wrote a memo declaring that the company's survival hinged on a shift to cloud computing.”) Instead, the company struggled with the role of this emerging business within its lucrative S&T segment: “Since 2008, Ray Ozzie had been incubating a highly secretive cloud infrastructure project with the code name Red Dog… The team was a side effort that was ignored by the mainstream of the S&T leadership. In late 2010, Ray Ozzie announced in a long internal memo that he was leaving Microsoft. He wrote in his departure email, ‘The one irrefutable truth is that in any large organization, any transformation that is to stick must come from within.’ While Red Dog was still in incubation with limited revenue, Ozzie was correct that Microsoft’s transformation would come from within.”

In early 2011, a few months after Ozzie announced that he was leaving Microsoft, Ballmer informed Nadella that he would become the leader of the S&T business (“I was given the news of my new role not even a week before I got the job”). By that time, Nadella argued that they had now fallen well behind their competitor in Seattle: “When I took over, analysts estimated that cloud revenues were already in the multi-billions of dollars, with Amazon in the lead and Microsoft nowhere to be seen… They were the clear leader, building a huge business without any real challenge from Microsoft.”

In his previous role in Microsoft’s Online Services Division (Bing), Nadella had already come to appreciate the value of cloud services. He needed to convince the S&T team – which, as noted earlier, was currently reporting stellar financial results – to place a higher priority on supporting Red Dog:

“The organization was deeply divided on the importance of the cloud… The division’s leaders would say, ‘Yes, there is this cloud thing,’ and ‘We should incubate it,’ but then they would quickly shift to warning, ‘Remember, we’ve got to focus on our server business.’ The servers that had made S&T a force within Microsoft and the industry were now holding them back, discouraging them from innovating and growing with the times.”

Nadella was convinced on where the future was headed – but he also recognized Microsoft would not succeed if he was unable to get the S&T team to share his vision of the future for their business (which he had just joined). As he wrote, “I had to convince my team to adapt a counterintuitive strategy – to shift focus from the big S&T business that paid everyone’s salary to the tiny cloud business with almost no revenue. To win their support, I needed to build shared context… I decided not to bring my old team from Bing with me. It was important that the transformation come from within, from the core. It’s the only way to make change sustainable.”

After meeting with each member of the S&T leadership team, a vision emerged around hybrid cloud solutions: “though we would be cloud-first, our server strength would enable us to differentiate ourselves to customers who wanted both private, on-premise servers and access to the public cloud.”

Shortly after, Nadella took the Red Dog side project, which had since been renamed Azure, and made it a top priority in S&T (Scott Guthrie, who now runs Microsoft’s Cloud business, was brought on as an early engineering lead). In summary, efforts to scale the cloud business in the early 2010’s required Nadella to navigate technical, financial, commercial, and cultural roadblocks. When he was named the third CEO in Microsoft’s history in February 2014, Nadella wrote the following in an email to employees:

“While we have seen great success, we are hungry to do more. Our industry does not respect tradition - it only respects innovation. This is a critical time for the industry and for Microsoft. Make no mistake, we are headed for greater places - as technology evolves and we evolve with and ahead of it. Our job is to ensure Microsoft thrives in a mobile and cloud-first world.”

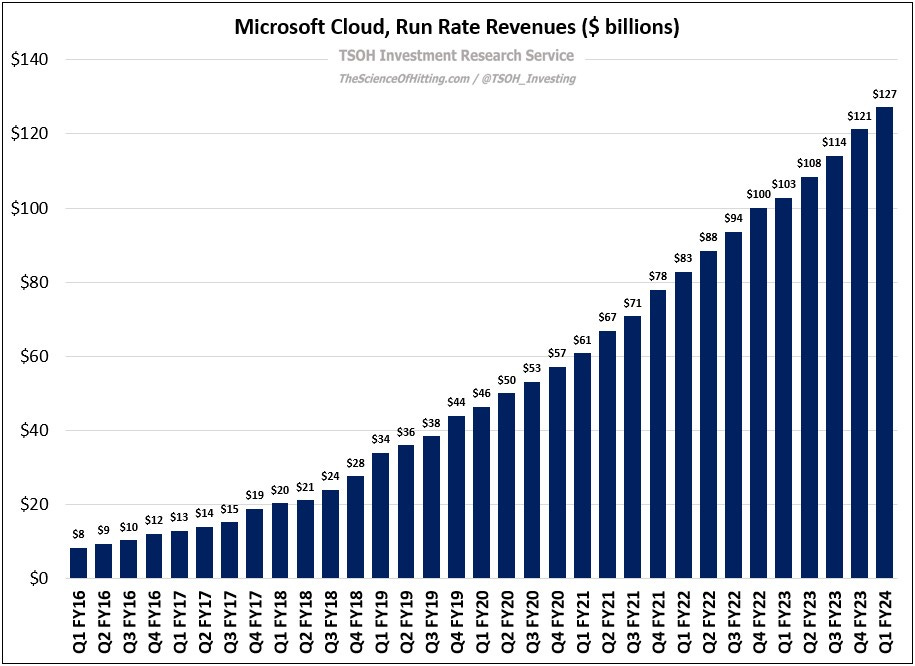

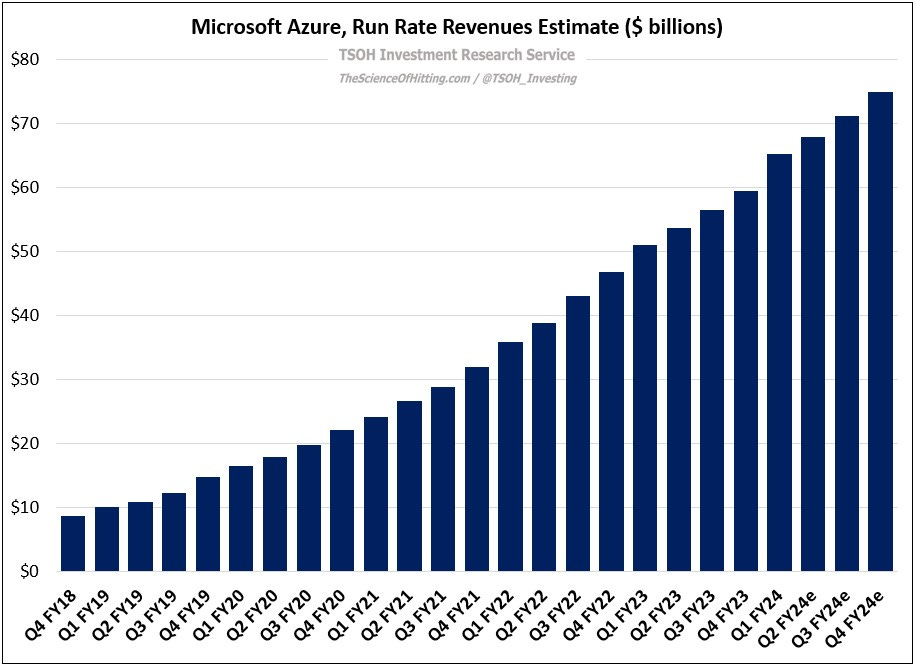

Just over a year later, at an investor event in April 2015, Nadella set an audacious goal for Microsoft’s cloud businesses: “We have an ambition to get to $20 billion of run rate revenues by FY18; that’s our target.” (At that time, run rate Cloud revenues were ~$6.3 billion.) The company ultimately beat its target - run rate revenues were ~$28 billion at the close of FY18 - and has kept marching higher ever since: as of Q1 FY24, run rate revenues for Microsoft Cloud are now at ~$127 billion – nearly 50% higher than the company’s total revenues when Nadella became CEO. And Azure, the cloud project with immaterial revenues and an uncertain future as Microsoft entered the 2010’s, is on pace to exit FY24 with run rate revenues of ~$75 billion.

Conclusion

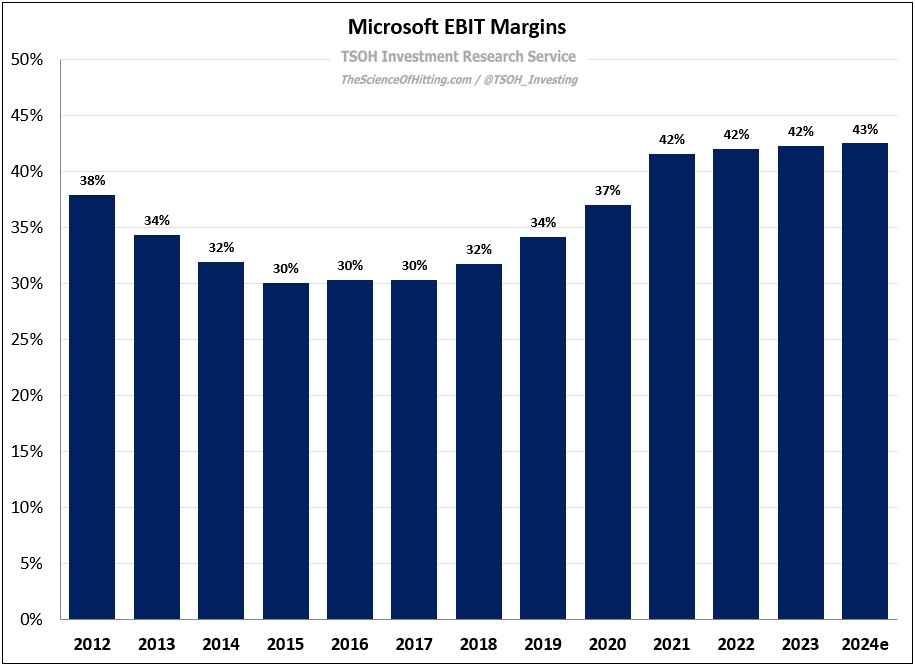

It’s interesting to consider how close Microsoft came to a very different course of events. In a different scenario, where 68-year old Alan Mulally took charge, how would this have played out? Would he have shared Nadella’s conviction and willingness to accept material P&L pressure through the mid-2010’s that ultimately led to the astounding revenue and earnings growth that we’ve witnessed in recent years? Even if open to the idea, would Mulally truly have the technological prowess and cultural understanding to effectively navigate internal barriers at S&T? (On the cultural concerns, remember Nadella had already been at Microsoft for 20+ years when the board was searching for the next CEO; when asked what he saw as his primary focus, he said “to ruthlessly remove any obstacles that impede us from innovating”.)

I obviously don’t know the answer to those questions with certainty, but I suspect it could’ve been a very different outcome (and not in a good way). I don’t think it’s a stretch to conclude that, with the benefit of hindsight, naming Nadella CEO was a critical decision that has greatly impacted the company’s current position in the technology industry. (By the way, the above discussion on cloud computing also applies in other areas, like AI; it’s clear from “Hit Refresh” that he understood in the mid-2010’s where the world was headed.)

What’s the takeaway for investors?

First, I think we must recognize that managerial quality greatly influences a company’s ability to effectively execute a sound long-term strategy, which will have a meaningful influence on business outcomes over a long enough time period (with that “execution” covering internal / cultural considerations, capital allocation, etc.). Second, as we think about making investment decisions, it’s critical to give considerations like managerial quality their proper weighting, even though they cannot be easily quantified. Said differently, in those situations where you’re confident that you’ve identified a one-of-a-kind leader, even if it’s years after they’ve been in charge, act accordingly; I think it would be a grave mistake to make an investment decision that was overly weighted to something like a near term P/E multiple in that situation. (Like if Langone sold HD in the 1980’s simply because the forward P/E was >30x.)

Instead, you should recognize just how impactful the right people can be to the long-term value of an enterprise; that isn’t easily quantified (if at all), but that doesn’t change the reality that it’s incredibly important over time.

As a corollary, long-term investors should be sure that they give both the quality of the business and the quality of the management that they’re partnering with due consideration when analyzing potential investments.

In the ideal scenario, when those two pieces come together, it leads to outcomes that make traditional valuation metrics look foolish in due time.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty, or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions, and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and are subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.