AWS: "Scoring 1,000 Runs"

“We completely reinvented the way companies buy computation.”

“One area where I think we are especially distinctive is failure. I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment. Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there. Outsized returns often come from betting against conventional wisdom, and conventional wisdom is usually right. Given a ten percent chance of a 100 times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten. We all know that if you swing for the fences, you’re going to strike out a lot, but you’re also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs. This long-tailed distribution of returns is why it’s important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments.”

- Jeff Bezos, 2015 Letter to Shareholders

The focus of today’s write-up is Amazon Web Services (AWS) - one of the greatest examples of invention and value creation in modern business history. (Besides being a fascinating story, it’s also of much interest to me given my sizable investment in Microsoft.)

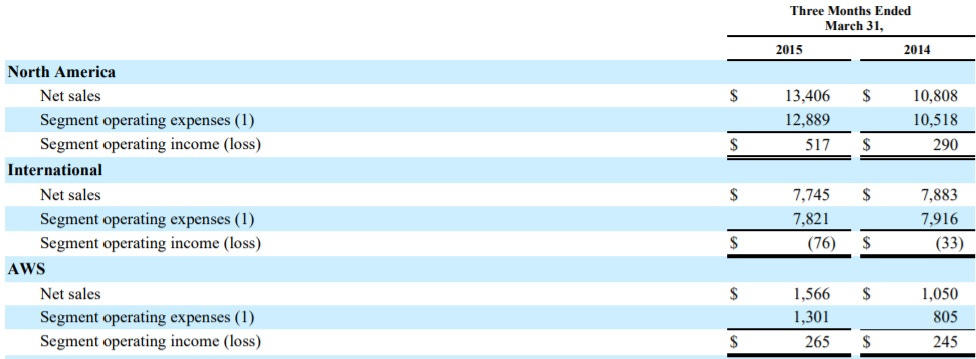

In April 2015, Amazon disclosed the financials for AWS for the first time. As shown below, the segment delivered $1.6 billion in sales in Q1 FY2015, an increase of roughly 50% from the year ago period. In addition, AWS generated $265 million in operating income (mid-teens margins), which was in stark contrast to the belief of many outside observers (“its margins are razor-thin”). Note, for example, that Citi analysts estimated in early 2015 that AWS would generate $9.2 billion in sales and less than $100 million in EBIT in 2016; when Amazon reported its FY16 results, AWS delivered $12.2 billion in sales and $3.1 billion in EBIT. The financial success of Amazon’s cloud computing business, a closely guarded secret for years, was now out in the open for all to see (AWS CEO Andy Jassy: “I was not excited about breaking our financials out because they contained useful competitive information.”)

In the Q1 FY15 quarterly press release, CEO Jeff Bezos said the following:

“Amazon Web Services is a $5 billion business and still growing fast - in fact it’s accelerating. Born a decade ago, AWS is a good example of how we approach ideas and risk-taking at Amazon. We strive to focus relentlessly on the customer, innovate rapidly, and drive operational excellence. We manage by two seemingly contradictory traits: impatience to deliver faster and a willingness to think long term. We are so grateful to our AWS customers and remain dedicated to inventing on their behalf.”

The initial idea for AWS came as a response to Amazon’s own internal needs (from “Amazon Unbound”):

“Contemplating the way his engineers worked, and the expertise the company had developed in building a stable computing infrastructure that could withstand enormous seasonal spikes in traffic, Bezos conceived of a new business called Amazon Web Services. The idea was that Amazon would sell raw computing power to other organizations, who could access it online and use it to economically run their own operations.”

The first time Bezos wrote about AWS was in the 2006 shareholder letter:

“With AWS, we’re building a new business focused on a new customer set … software developers. We currently offer ten different web services and have built a community of over 240,000 registered developers. We’re targeting broad needs universally faced by developers, such as data storage and compute capacity - areas in which developers have asked for help, and in which we have deep expertise from scaling Amazon.com over the last twelve years. We’re well positioned to do it, it’s highly differentiated, and it can be a significant, financially attractive business over time.”

In the early days, AWS was primarily used by companies like Pinterest, Airbnb, and Netflix (Bill Gurley in 2009: “From where I sit as a VC, it was obvious they were winning… you could see it in the number of startups they were adding to their platform.”). These customers valued the ability to quickly provision capacity for storage and computing resources to match their breakneck - and often unpredictable - growth (“in twenty seconds, we can double our server capacity “). Instead of significant up-front investments to buy their own equipment, they “rented” the AWS infrastructure on a pay-as-you-go basis (“transform capital expenses into a variable cost”).

As Bezos told Bloomberg in 2006, “All the things you need to build great Web-scale applications are already in the guts of Amazon. The only difference is, we're now exposing the guts, making [them] available to others.”

Zooming out, the scale advantages inherent in cloud computing have worked to the benefit of all involved: the pooling of workloads across a diverse customer base gives AWS much higher utilization rates than do-it-yourself data centers (something Amazon was familiar with given the seasonality in its e-commerce business) which results in higher capital efficiency on massive (cumulative) fixed cost investments - enabling the public cloud providers to offer attractive prices that more closely align with actual usage. (“Typical single-company data centers operate at roughly 18% server utilization. They need that excess capacity to handle large usage spikes.”)

This value proposition was a gamechanger for startups (from Jassy):

“We tried to imagine a student in a dorm room who would have at his or her disposal the same infrastructure as the largest companies in the world. We thought it was a great playing-field leveler for startups and smaller companies to have the same cost structure as big companies.”

Bezos’ vision of what AWS had accomplished was even grander:

“We completely reinvented the way that companies buy computation.”

Management manically focused on execution - the underlying performance of AWS - to ensure it lived up to customers’ expectations. For example, as discussed by Brad Stone in “Amazon Unbound”, “AWS engineers were given pagers and were assigned to on-call rotations, when they were expected to be available at all hours to address system outages.” In addition, high level AWS execs and engineers would meet every Wednesday to review the technical performance of the service. As retold by Stone, Andy Jassy introduced uncertainty into those meetings to keep the team on their toes:

“Around the big table at the center of the room sat more than forty vice presidents and directors, while hundreds of others stood in the wings or listened over the phone from around the world. On one side of the room was a multicolored roulette wheel, with different web services, like EC2, Redshift, and Aurora, listed around the perimeter. Each week the wheel was spun with the goal being, Jassy said, to make sure managers were ‘on top of the key metrics of their service all week long, because they know there’s a chance they may have to speak to it in detail’… For managers, a failure to deeply understand and communicate the operational posture of their service could amount to career death.”

Over time, AWS introduced services like Redshift (data warehouse), Aurora (MySQL database), and Lambda (serverless computing). With these offerings, they began selling higher-value services that ran on top of the “cheap, raw, computing power”. This was a big deal: moving from pure compute to a full tech (software) stack broadened the customer appeal of the public cloud and greatly improved its long-term business prospects (“Once they moved data onto Amazon’s servers, companies had little reason to endure the inconvenience of transferring it back out. They were also more likely to be attracted to the other profitable applications that AWS introduced.”). Of course, it also put AWS in direct competition with the established enterprise software companies like Microsoft and Oracle.

It’s not just the cloud service offerings that evolved. As Bezos wrote in his 2014 shareholder letter, the customer mix also matured over time to include enterprises, nonprofits, and government entities:

“Large enterprises have been coming on board, and they’re choosing to use AWS for the same primary reason the startups did: speed and agility… These are the main reasons AWS is growing so quickly. IT departments are recognizing that when they adopt AWS, they get more done. They spend less time on low value-add activities like managing datacenters, networking, operating system patches, capacity planning, database scaling, and so on and so on. Just as important, they get access to powerful API’s and tools that dramatically simplify building scalable, secure, robust, high-performance systems. And those API’s and tools are continuously and seamlessly upgraded behind the scenes, without customer effort.”

While anecdotal, I’ve seen several data points over the years to support that conclusion (of course, the incessant growth of the public cloud market is pretty compelling evidence on its own).

For example, as it relates to costs savings, General Electric disclosed at the 2018 AWS Summit in New York that they had recognized total cost of ownership (TCO) savings of ~50% as they migrated a majority of their workloads to the cloud. (“Direct cost improvements from operating in the cloud versus on premises vary, but a reasonable estimate is 30%”.)

Or, as it relates to speed and agility, the CTO of Expedia said the following in 2017: “Before running analytics workloads on AWS, it took us three hours to analyze five days of performance metrics. Now we can analyze seven days of data in 30 seconds - that’s 360 times faster. With this kind of speed, we can quickly gain insights and drive the innovations that our customers expect as they interact with our brands around the world.”

Finally, Amazon experienced these benefits itself when they migrated the e-commerce business off of legacy Oracle databases (“after several years of work”). As noted in a 2019 post on the AWS blog, this led to meaningful cost savings: “We reduced our database costs by over 60% on top of the heavily discounted rate we negotiated based on our scale. Customers regularly report cost savings of 90% by switching from Oracle to AWS.”

The benefits realized by end customers, in terms of speed, scalability, availability, security, and TCO savings, has been the primary driver of the prodigious growth in cloud computing over the past decade.

The most interesting part of the AWS story is how long it took competitors like Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle to recognize the long-term opportunity (and threat) from cloud computing; as Bezos noted in a September 2018 interview, “A business miracle happened. This never happens. This is like the greatest piece of luck in the history of business, so far as I know: we faced no like-minded competition for seven years. It’s unbelievable.”

As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella admitted in 2017, they were late to the game (a classic innovator’s dilemma): “We had a very successful server business… But we knew by looking at what Amazon was doing that we needed to reinvent ourselves. And, by the way, the margins we’re going to be very, very different – it was a tough challenge… I wish we had started even earlier. You’ve got to be great at responding to these shifts in business models…”

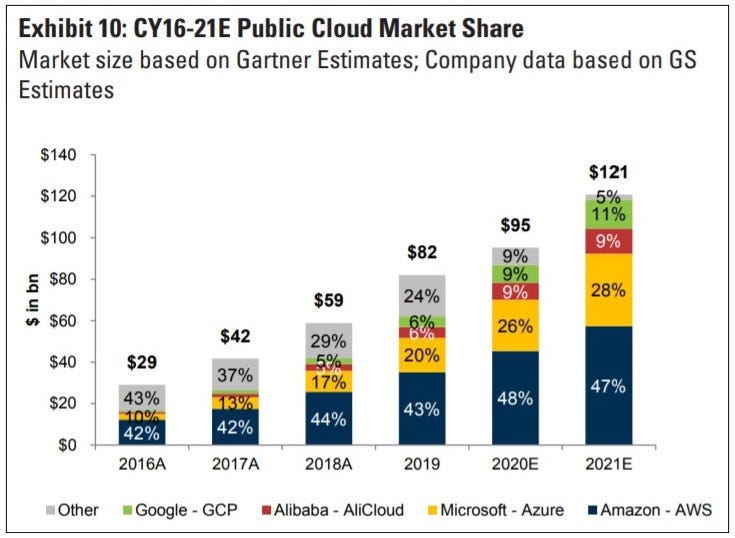

That multi-year head start has proven to be an immense advantage: despite persistent investment and focus by Microsoft (Azure) and Google (GCP) over the past 5+ years, AWS still maintains a significant lead, with a public cloud market share (IaaS + PaaS) in excess of 40% (Amazon’s CFO: “We think that we have a very big lead in this space because of our many years of investment... what you're seeing is the convergence of a lot of investment, a lot of operational efficiency and a lot of innovation on behalf of customers”).

Conclusion

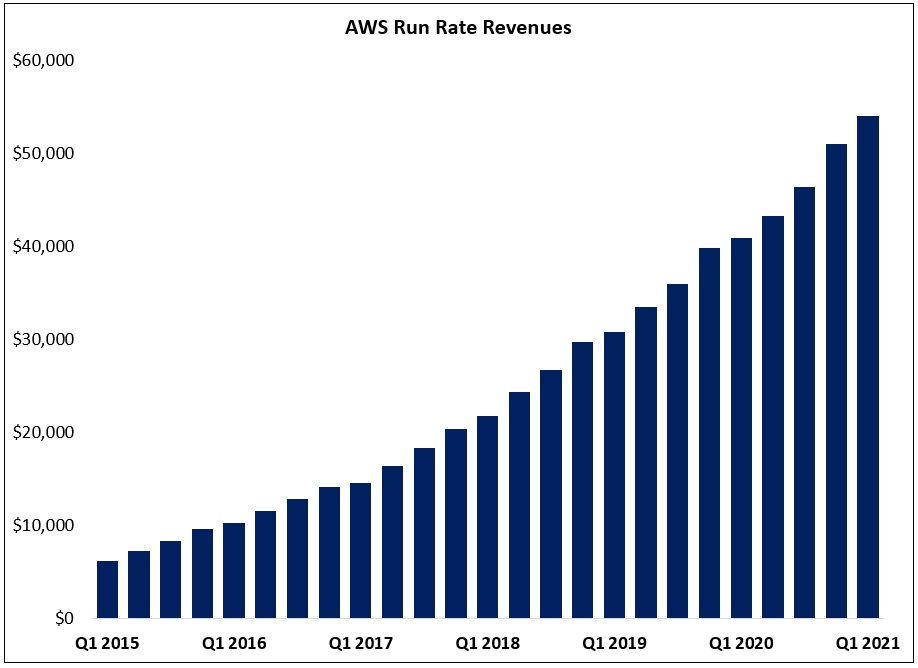

In Q1 FY15, the first time AWS financial results were disclosed, run rate revenues were just north of $6 billion. As shown below, the business has continued to grow rapidly – with run rate revenues in Q1 FY21 crossing $54 billion (trailing six-year CAGR of +43%).

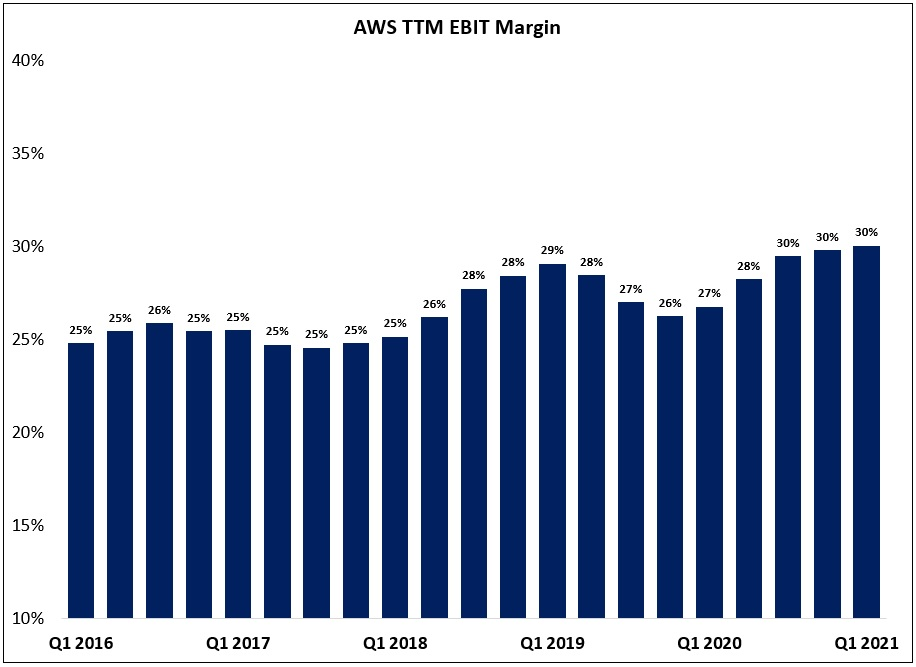

In addition, despite significant ongoing investments in infrastructure, headcount, and R&D, as well as heightened competition from Microsoft and Google, the business has reported meaningful operating leverage: trailing twelve month (TTM) operating margins in Q1 FY21 were 30%, about 500 basis points higher than what the business generated 3 - 5 years ago.

The net result is that AWS is now generating run rate operating income of $16 billion a year. With the top line still growing north of 30%+ YoY, it’s likely that AWS will generate $100 billion in revenues and $30 billion in operating income by 2025 (and Jassy believes “it’s still very early days in people moving to the cloud”). Over the course of 15 years, Amazon has created a business out of thin air that would command a standalone valuation in excess of $500 billion.

And as Chamath Palihapitiya of Social Capital wrote in 2016, the long-term addressable market for AWS is unimaginably large (as discussed in the April 2021 Portfolio Review, research firm Gartner estimates that cloud penetration of the long-term enterprise IT market opportunity is still below 20%): “AWS is a tax on the compute economy… If you believe that over time the software industry is a deca-trillion dollar industry, ask yourself how valuable a company is who taxes the majority of that industry… I don't see any cleaner monopoly available to buy in the public markets right now.”

I’ll leave the last word to Bezos (from the 2014 shareholder letter):

“AWS is one of those dreamy business offerings that can be serving customers and earning financial returns for many years into the future. Why am I optimistic? For one thing, the size of the opportunity is big, ultimately encompassing global spend on servers, networking, datacenters, infrastructure software, databases, data warehouses, and more. Similar to the way I think about Amazon retail, for all practical purposes, I believe AWS is market-size unconstrained.”

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

Their lead reminds me a bit of Netflix's lead on content. That first-mover advantage combined with incredibly savvy management and a little bit of luck...damn.

I'm starting to lick my chops on Amazon...