"Always Looking For Context"

Macroeconomic Factors and Long-Term Investing

During a recent episode of the “Focused Compounding” podcast, Geoff Gannon and Andrew Kuhn discussed their perspective on the role that macroeconomic considerations play in Warren Buffett’s investment process. The conversation included a reference to the following from an interview with Alice Schroeder: “Buffett is keenly aware of the economic cycle and the relevant data. He uses economic data to put context around what is happening in specific businesses, to visualize macro risks at the company specific level… For example, he knew to some degree that we were in a bubble leading up to 2008… He didn’t get into the mortgage business, although you’d better believe people were showing up on his doorstep urging him with all sorts of apparently lucrative deals. The economy is context… He’s always looking for context. Having an interest in a broad sweep of history provides vast context for making many decisions because it enables analogies. And that, I think, has been very helpful for him in avoiding fallacies such as ‘this time it’s different.’ It allows him to make analogies between industries [over time] - for example, between the internet stocks and the early auto stocks, as he did in the speech at Sun Valley [in July 1999].”

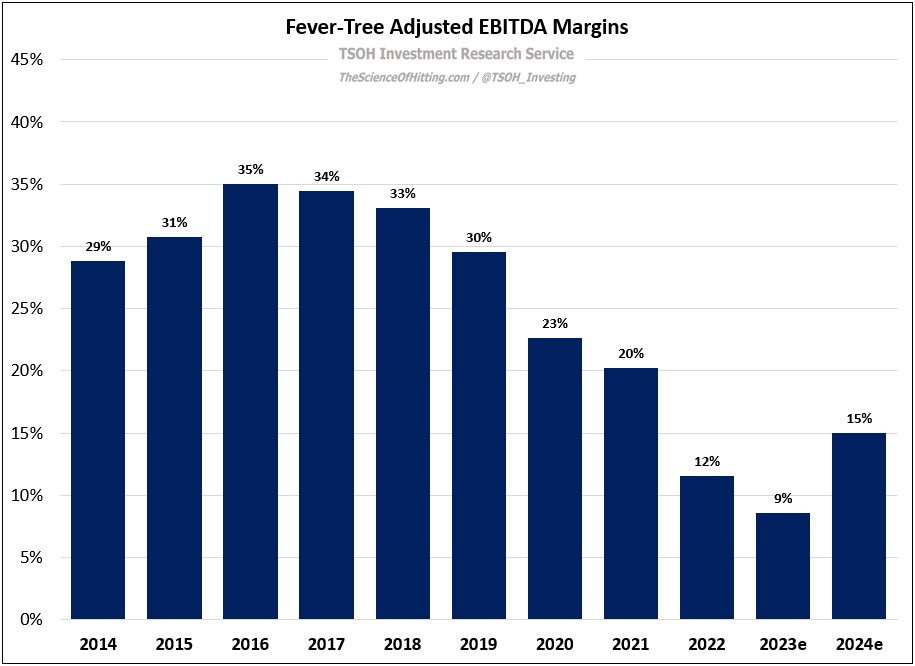

Fever-Tree is a good example of how macroeconomic considerations can have a material impact on an investment thesis; FT’s financials have been significantly impacted for a sustained period by factors largely beyond their control (input costs for energy / product packaging, shipping rates, etc.). You might argue that an investor who bought FT five years ago appears largely correct on their bet in terms of its competitive position and long-term growth prospects – but with the stock down >60% over that period due to the large COGS headwinds, that probably wouldn’t provide them much comfort.

With hindsight, here are two questions the FT investor might ask as they grade their investment: (1) Were these factors knowable / predictable? (2) Even if they (roughly) were, should it have impacted their decision-making?

The answer to the first question, for me, would’ve been no. While I surely would’ve appreciated that something like this could happen, I have no reason to believe I can properly handicap whether and when it would happen.

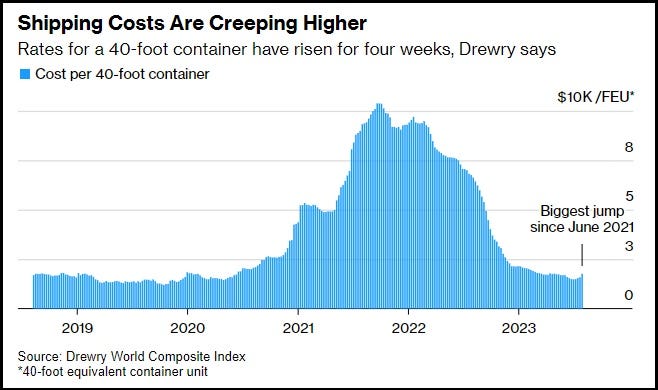

For example, the following chart shows spot rates for shipping containers on certain trade routes between the U.S., Asia, and Europe. If you asked me to predict the future trajectory for this index, my best guess is it will look the 2019 section more often than not (relatively stable), with periodic bouts of significant volatility. That said, I would have zero conviction on when that was likely to happen, how significant it would be, and how long it would last for.

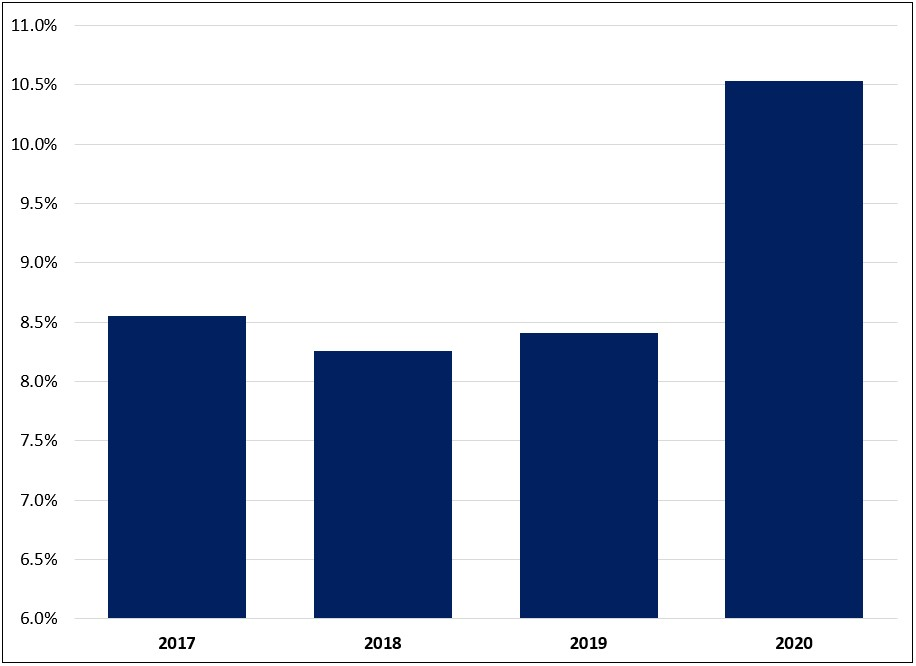

That said, I would probably be comfortable assuming that a period of very significant price increases, like what was experience throughout 2021, would normalize over time (eventually). From that perspective, let’s view another data set. The following is the margin trajectory of an unidentified company. The difference between ~10.5% profit margins in 2020 and ~8.5% profit margins in 2019 is a ~25% tailwind to earnings – much less extreme than the 3x – 4x increase experienced for shipping container costs in the above example, but nothing to scoff at either. For this metric, was an (eventual) return to the 2017 - 2019 average a knowable / predictable outcome?

Well, with the benefit of hindsight, the answer is proving to be “yes”. Here’s the complete data set for Dollar General’s EBIT margins; FY23e is not only well below the 2020 highs, but ~200 basis points lower than what DG reported before the pandemic (trailing five-year average for 2015 – 2019).

The stock traded for $200 - $250 per share for long stretches throughout 2022; by comparison, if we apply a normalized EBIT margin of ~8% to current (run rate) revenues, EPS for the business is $9.0 - $9.5 per share (~25x earnings). That’s a long way of saying “macro”, used as a catch-all term for the pandemic-related impact on DG’s store volumes / product mix, COGS and SG&A inflation, etc., proved to be a real risk to its short-term profitability. (As I discussed earlier this month, it is also difficult to parse out what’s macro versus company specific). If you think this mean reversion was predictable and if you’re keen on avoiding these bouts of (significant) stock price pressure, you should watch them closely as part of your process. (Now, we could also find plenty of counterexamples: when Fever-Tree’s EBITDA margins contracted from 30% in FY19 to 20% in FY21 on macro pressures, was it time to buy? Calling for that reversion has not worked out so far…)

That brings us to the second question from above: if you operate from the perspective that these “macro” developments are knowable / predictable, how would it impact your decision-making? I think that answer is at least partly dependent upon your investment approach. For example, as discussed in “My Investment Philosophy”, my north star is to own high-quality businesses for the long-term (that’s the approach that feels most appropriate for me given my time horizon, mindset, etc.). I believe this approach, when reinforced by rules around portfolio decision-making, has the necessary inputs to develop an uncommon level of earned conviction / trust, as appropriate, in certain companies and management teams (“you build trust through consistency over time”). That said, it’s an approach that probably isn’t as well suited for trying to avoid those periods of stress (or, in situations that really go poorly, value traps). Put simply, I think your perspective on the “right” way to invest should impact your answer. (As discussed in “The Evolution of A Value Investor”, I used to think about these different approaches in terms of being “right” or “wrong”. I now tend to think about them in terms of trade-offs.)

Clayton Homes and The U.S. Housing Market

I think the industry developments that led to Berkshire Hathaway’s acquisition of Clayton Homes, along with Buffett’s and Munger’s views on the broader (stick-built) U.S. housing market in the years leading up to the 2007 – 2008 financial crisis, is a great example of how they use macroeconomic data “to put context around what is happening”. When Buffett discussed the ~$1.7 billion acquisition of Clayton Homes at the 2003 shareholder meeting, he explained how the manufactured housing industry had been devastated in recent years due to financing / credit issues and subsequent volume declines (by 2003, industry volumes had declined ~65% from five years earlier):

WB: “Practically everybody in manufactured housing is losing money now… What was going on a few years ago, where a manufacturer would sell a house to a dealer, and then the dealer could borrow 125% - 130% of the invoice price if he got some purchaser on the note that would give him some apparent down payment - that situation was built for disaster. At Clayton, the profit or loss off that home purchase goes until the obligation is fully paid for. So, if a dealer takes inadequate down payments or sells to people he shouldn’t be selling to, it’s going to be his problem; he’s going to get the repo back, he’s going to have to sell it himself, and he’s going to get the loss on the paper charged to him. That produces an entirely different kind of behavior at the retail level than occurred at many companies… If you read Jim Clayton’s book, he tells about when he bought his first home. He tells about some funny business in terms of how the manufacturer behaved, and he described some of the systems people used to game the financing. Those activities are coming home to roost in a huge way for both the manufactured housing companies and for the people that finance the retail paper. Clayton did it right, basically, and they’ll continue to do it right. Even so, there is such a stain over the whole manufactured housing industry, in terms of financing. Clayton is the only one that has been able to securitize – but without us, they wouldn’t be able to securitize to the extent that they could have a year ago. It’s an industry in big trouble; I think we will do fine because we’re in with a class player.”

Here’s my read on the investment: Clayton was the leader in a distressed industry, with that fact accounted for in the purchase price. The kicker was that the business was likely to benefit from Berkshire’s involvement (Buffett made that point clear in a press release published the day before Clayton shareholders were set to consider his offer: “Clayton’s financial needs are large and continuous… Clayton must have a dependable source of financing – under all circumstances – and Berkshire can provide it.”).

In addition, as discussed in the 2003 letter, Buffett developed a better understanding of what made Clayton unique after buying the distressed junk debt of Oakwood Homes, another company in the industry: “At the time, I did not understand how atrocious consumer-financing practices had become throughout most of the manufactured housing industry. But I learned: Oakwood rather promptly went bankrupt… Oakwood participated fully in the insanity. But Clayton, though it could not isolate itself from industry practices, behaved considerably better than its major competitors.” (In late 2003, Clayton agreed to buy Oakwood out of bankruptcy for $373 million.) When Buffett and Munger updated on manufacturing housing at the 2006 shareholder meeting, it became quite clear that what they had observed in manufactured housing was prevalent in the broader U.S. housing market: