Portillo's: "A Growth Story"

“There’s a graveyard full of restaurant companies that expanded too quickly; they lost their way and became a different version of themselves.”

- Portillo’s CEO Michael Osanloo

In August 2014, a half century after founder Dick Portillo opened his first hot dog stand in Villa Park, Illinois (“The Dog House”), the Portillo’s restaurant chain was sold to the private equity firm Berkshire Partners for ~$1 billion. (Dick Portillo: “I had two dozen suitors... Berkshire didn’t have the highest bid, but I felt that they truly understood how special our brand and culture was.”)

The company went public seven years later in October 2021, with the stock climbing nearly 50% at the IPO to ~$29 per share. The subsequent stock performance has disappointed: at ~$14 per share, PTLO is down ~70% from its all-time highs. On 2024e EBIT of ~$60 million, it’s valued at ~20x EV/EBIT.

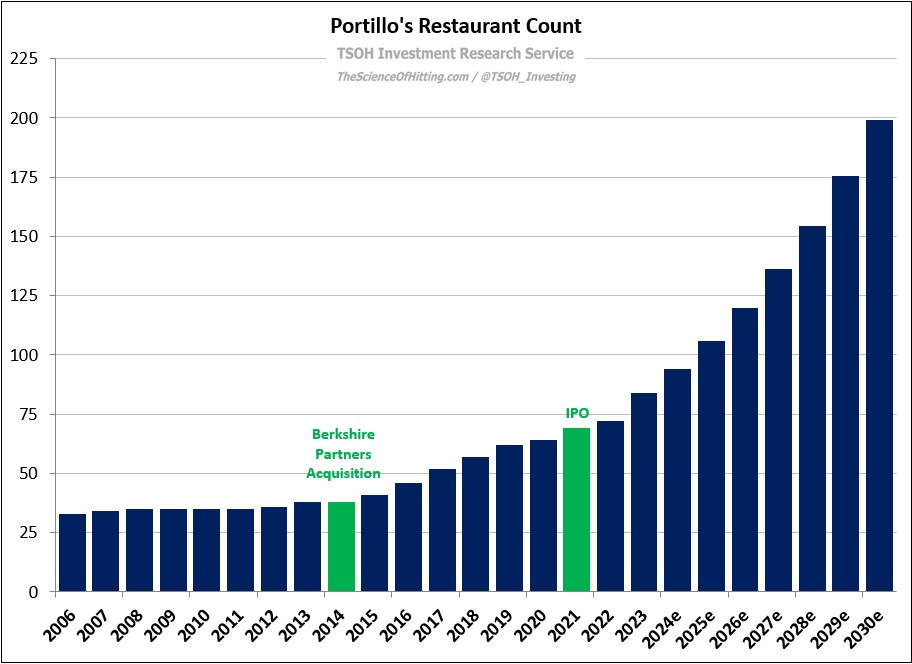

The biggest change in the strategy following the sale to Berkshire Partners was unit growth: it took 51 years to reach 38 locations (in 2014), with another 46 restaurants added over the next nine years (FY14 – FY23 CAGR of ~9%).

As discussed at the 2023 Investor Day, another acceleration is coming: plans call for long-term annualized growth of 12% - 15%, which puts the company on pace for roughly 200 units by 2030. As CEO Michael Osanloo said at the Investor Day, “Unit growth is a key driver for us… We are a growth story.”

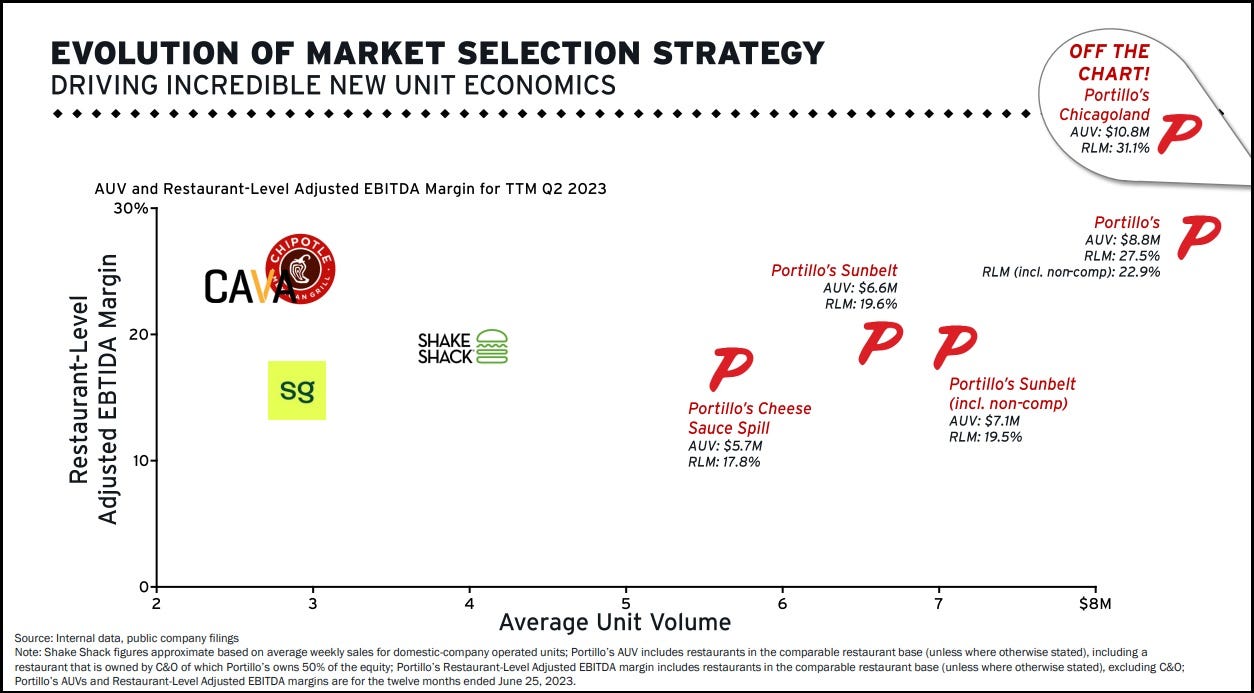

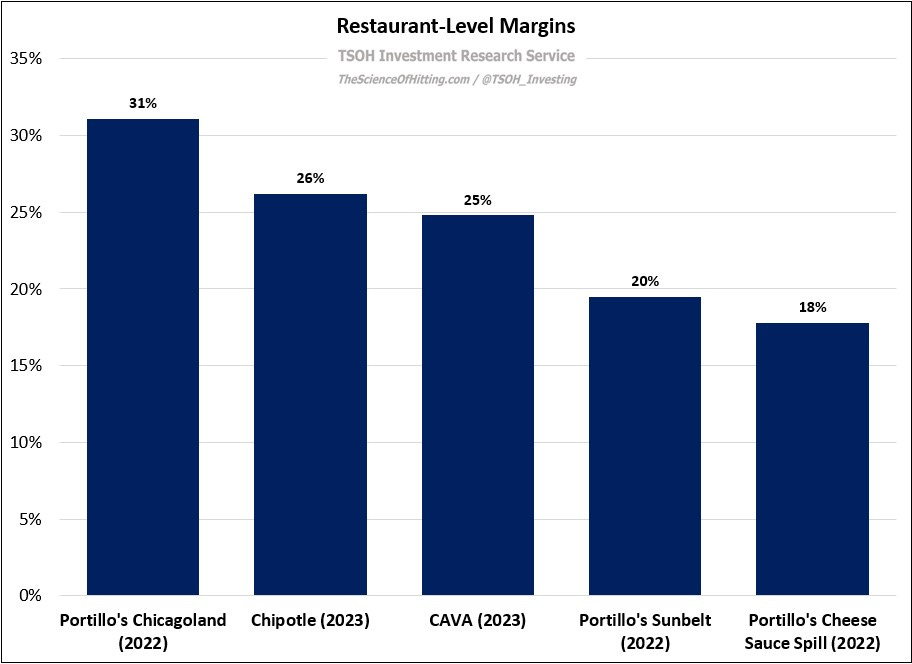

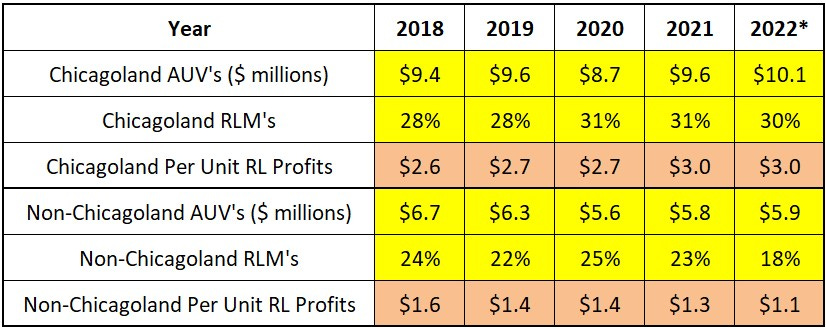

Today, Portillo’s is still largely a regional concept. It has a major presence in Illinois, and particularly in the Chicago area (Chicagoland): the state accounts for 48 of its 84 restaurants, including the winner of a 2018 TripAdvisor award for the #1 fast casual location in the country. Notably, while Portillo’s has higher average unit volumes (AUV’s) than any of its fast casual restaurant competitors, its results vary greatly by geography: as highlighted at the 2023 Investor Day, Portillo’s Chicagoland restaurants had AUV’s of $10.8 million, or ~60% higher than its non-Chicagoland locations. In addition, Chicagoland had ~31% restaurant-level margins (RLM’s), or ~1,200 basis points higher than the non-Chicagoland locations. (RLM is a measure of store level profitability; the difference from EBIT is that RLM excludes corporate G&A expenses, depreciation & amortization expenses, and pre-opening costs.)

What I find interesting about the above chart is how Portillo’s newer regions compare to the results from competitors like Chipotle and CAVA. As an example, despite AUV’s that are ~50% lower than Portillo’s non-Chicagoland locations, each of those fast casual chains has RLM’s that are ~500 basis points higher than the results reported for Portillo’s “Sunbelt” and “Cheese Sauce Spill” restaurants. This is an important point to understand: Portillo’s restaurants do not just have high AUV’s; they need high AUV’s.

That brings us back to the growth strategy: management wants Portillo’s to become a national brand, with future growth plans focused on the Sunbelt. (The first Portillo’s outside of Illinois opened in California in 2005; states like Arizona and Florida were originally selected because they are home to Chicago transplants and frequented by snowbirds.) Naturally, this change in strategy presents a risk: Portillo’s is expanding into regions where it has less operating experience and isn’t as well known. For a cautionary tale, look no further than their expansion in the “Cheese Sauce Spill” markets (a handful of states located next to Illinois like Wisconsin and Indiana): Portillo’s unit economics in those states are nowhere close to Chicagoland. (The data below is from the 2022 Investor Day deck.) For the company as a whole, this has pulled RLM’s to the mid-20’s – well below the results in Chicagoland.

Why is Portillo’s badly lagging its Chicagoland results in these states? As Osanloo said at the 2023 Investor Day, “Portillo’s actually performs better farther away from its home market [Sunbelt] than near it [Cheese Sauce Spill markets].” While he didn’t specifically explain why, I think this hints at the answer: “One of the lessons we learned is we need to be really great on site selection outside Chicago.” My suspicion is that the company paid its tuition over the past decade; national success required improvement in a few key areas, including site selection / design, reducing build costs, new store staffing / training, and supply chain management. This remains a work in progress, as we’re seeing with the roll-out of pick-up only restaurants. This, in my mind, is the key to long-term thesis: has Portillo’s has put the pieces in place to become a national brand with attractive unit economics?

If that long-term vision becomes a reality, owners will be well rewarded.

As we think about that question, note that Portillo’s is quite different from your average QSR or fast casual chain. Historically, Portillo’s restaurants have been very large and costly to build, with each having a unique style. (“We want the décor and the cosmetics to fit the local environment.”) This led to ample space for in-restaurant dining and double drive-thru lanes, along with a large kitchen / food prep area needed to support a wide ranging menu that includes salads, hot dogs, ribs, chicken sandwiches, Italian beef sandwiches, fish sandwiches, hamburgers, and their famous chocolate cake shake.

In “Out Of The Dog House”, Dick Portillo notes that he viewed this complexity as a feature, not a bug. As an example, he recounts a conversation with former McDonald’s CEO Jim Cantalupo: “Jim told me, ‘You know, if you could ever simplify this, you could open a lot of them, but it is very complex.’ I told Jim I didn’t want to simplify it because that would invite competition… I purposely designed the most complicated fast-casual business in the industry to beat the chains that I saw as my competition – McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s… Portillo’s moat is the complexity of the business.”