CAVA: The Next Chipotle?

CAVA’s story began in 2006, when its three co-founders - childhood friends Ted Xenohristos, Ike Grigoropoulos, and Dimitri Moshovitis - opened a traditional Mediterranean restaurant in Maryland called CAVA Mezze. Two years later, in 2008, they started selling CAVA branded dips and spreads at grocery stores, with former equity trader Brett Schulman hired to lead those efforts (Schulman became CEO of CAVA in 2010, a position he still holds today). A major turning point in the story came in 2011, when CAVA opened its first fast-casual restaurant (a “walk-the-line” model à la Chipotle – pick your base, protein, and toppings, with your meal prepared in front of you).

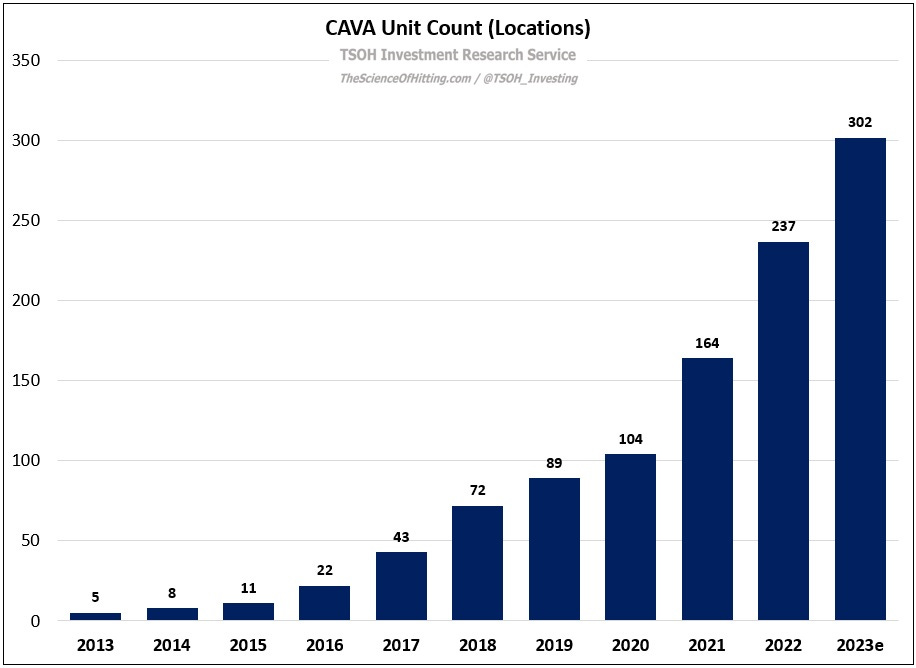

In 2018, by which point CAVA had grown to ~70 locations, a transformative deal was announced: the acquisition of Zoes Kitchen, a Mediterranean chain with ~260 units, for ~$300 million (“they have a great real estate footprint, especially in the South”). The deal was financed through a “significant equity investment” in CAVA by Act III Holdings, Ron Shaich’s financing group (Shaich founded Panera Bread and served as the chain’s CEO for more than 30 years; he has been Chairman of the Board at CAVA since late 2018). This led to a massive ramp in CAVA’s unit count: the company expects to have more than 300 locations throughout the U.S. by year end, up ~3x from 2020.

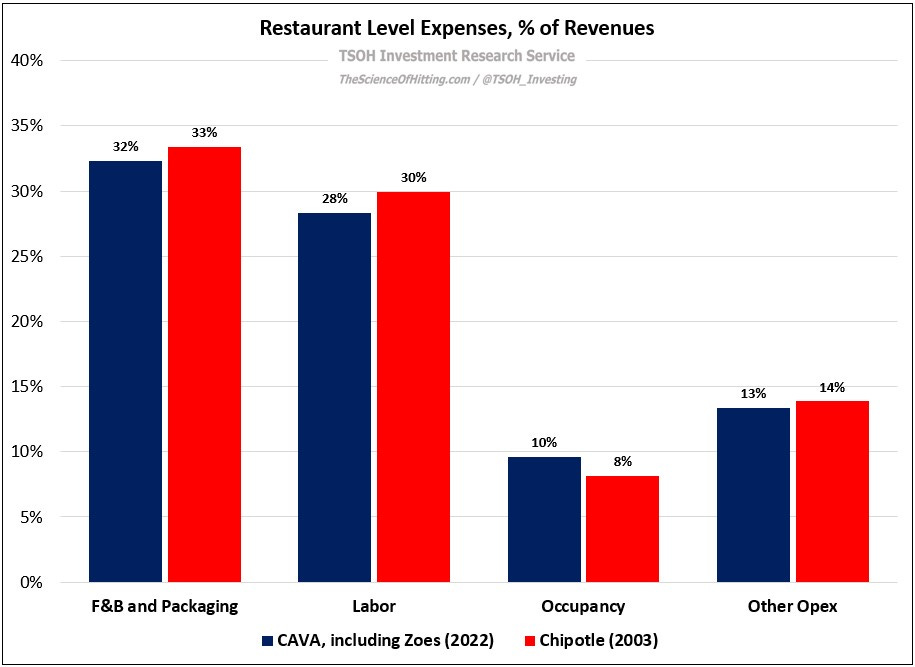

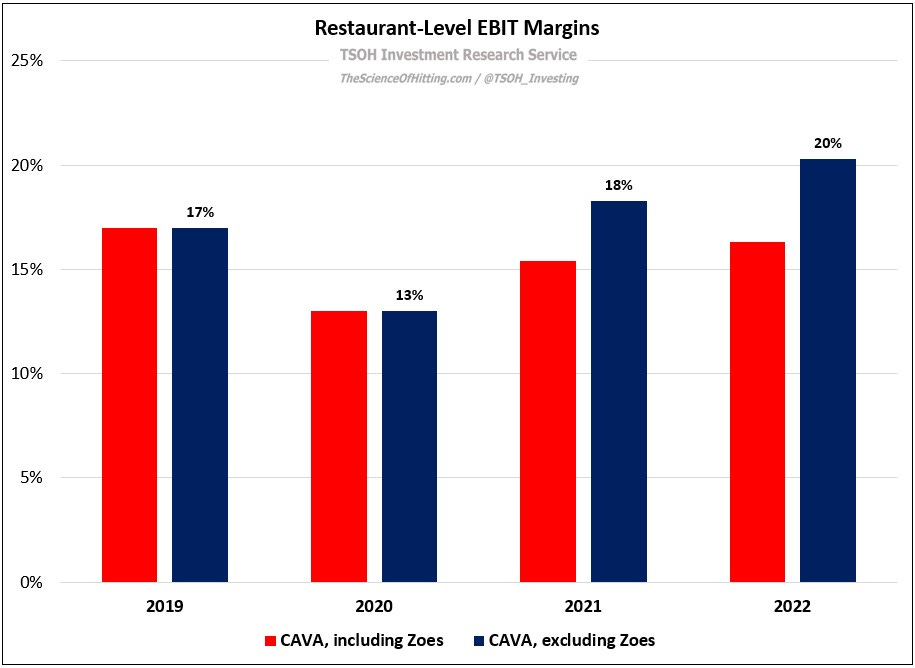

A natural place to start our analysis is with the current state of the business: how does CAVA’s financial performance compare to a best-in-class operator when they were at a similar size - for example, Chipotle in the early 2000’s? (As discussed in “We Had Lines Out The Door”, Chipotle’s early growth greatly benefited from the ~$400 million invested by McDonald’s, in addition to other operational learnings on real estate, supply chains, etc., from the burger chain.) Let’s use 2003, a year where Chipotle finished with 298 stores, as a point of comparison. In that year, Chipotle generated $316 million in revenues, with AUV’s for stores open 12+ months of ~$1.3 million. The company spent $268 million on restaurant-level expenses, including its food, beverage, and packaging costs, labor costs, occupancy, utilities, etc.; those expenses amounted to ~85% of Chipotle’s revenues in 2003, leaving restaurant-level operating margins of ~15%. The 2022 results at CAVA, including the remaining Zoes units that haven’t been closed / converted, were in the same ballpark (restaurant-level EBIT margins of ~16% for the year).

If we exclude Zoes and look solely at CAVA branded units, restaurant-level EBIT margins were ~20%, or ~500 basis points higher than Chipotle in 2003. (In Q1 FY23, CAVA’s restaurant-level EBIT margins were at ~25%.)

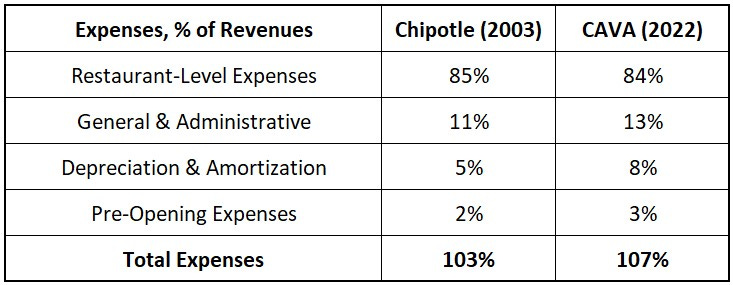

Where the comparison gets messier / less encouraging is on the “below the line” expenses - G&A, depreciation & amortization, and pre-opening costs (all of which are excluded from the restaurant-level calculation). At Chipotle, these expenses totaled $55 million in 2003, or ~18% of sales. The difference between restaurant-level margins (~15%) and the below the line expenses (~18%) is how we get to CMG’s 2005 EBIT margins (-3%). As a percentage of revenues, CAVA’s below the line expenses are meaningfully higher than Chipotle’s: even if we exclude all restructuring expenses - which were not insignificant at ~5% of sales - CAVA’s below the line expenses (G&A, D&A, and preopening costs) were $132 million in 2022, or ~24% of the company’s fast casual revenues (ex CPG). If we look at CAVA’s overall results (including non-converted Zoes), the below the line expenses are the primary reason why CAVA’s financials are worse than Chipotle’s at a similar point in their lifecycle (again, ex significant restructuring costs at CAVA).

Why are CAVA’s below the line expenses outsized relative to Chipotle? As I ran through the possible explanations, three things stood out to me.