In 2007, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia had an idea.

The two roommates, who were looking for a way to help pay the rent on their San Francisco apartment, noticed that a conference was attracting thousands of visitors to the city, leaving few vacancies at local hotels. If they could “rent” spare space in their apartment for a few nights, it would help them pay the bills. Chesky and Gebbia created a website called AirBedandBreakfast.com (“it’s like Craigslist and CouchSurfing.com, but classier”), and a few days later, three guests slept on blow-up mattresses on their apartment floor (for $80 a night). Chesky and Gebbia made about $1,000 from “renting” their apartment - and with that, the home-sharing platform Airbnb was born.

But in the early days, they faced numerous challenges. First, they had to prove home-sharing was something people actually wanted (“Strangers will never stay in each other’s homes”). Second, Chesky and Gebbia were industrial designers; they were outliers in the sense that they didn’t have the pedigree of tech founders like Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook or Sergey Brin and Larry Page at Google. As Chesky, Airbnb’s CEO, would later recount, they struggled to gain any traction with potential investors:

“We probably got 20 introductions… Everyone ran away from the idea. No one funded us. The first reason was Joe and I were designers. And as far as they were concerned, designers didn’t start companies.”

After running up tens of thousands of dollars in credit card debt, and without much to show for it (18 months in, the site only received 10 - 20 bookings per day), the founders had a new idea: “We didn’t make a lot of money with air beds, so we thought, well, we’re Air Bed and Breakfast, let’s go into the breakfast business.” They decided to create 1,000 boxes of collectible breakfast cereal based on the candidates in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election (Obama O’s and Cap’n McCain’s). Amazingly, they sold nearly 1,000 boxes of cereal for $40 each, with net proceeds of $30,000.

As Chesky recalled, “This is actually how we funded the company.”

Chesky, Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk (the third co-founder) leveraged their success with the cereals into a slot at Y Combinator, a startup incubator, in 2009 (came with $20,000 in seed funding for a 6% stake in the company); shortly after, they received $615,000 of funding, primarily from VC firm Sequoia Capital, at a $2.4 million valuation. (Chesky: “The moment Sequoia funded us, the rocket ship took off. There was no turning back.”)

Over the next decade, as Airbnb grew, the simple idea of sharing one’s home was presented with some previously overlooked externalities: “When we started Airbnb, we didn’t fathom millions of people doing this. I didn’t consider landlords. I didn’t consider cities. It grew to be so much bigger… It became very clear that we had to be much more mindful about how we designed the platform.” For years, the company has faced pushback from politicians, unions, and residents in major cities like Paris, London, New York City, Berlin, and Barcelona. Those issues have not been completely resolved – NYC is still a headache, as it has been since the Multiple-Dwelling Law was passed in 2010 – but Airbnb has made significant progress in cities all around the world (“We now collect and remit taxes in 30,000 jurisdictions.”). Importantly, at its current scale, the company is in a position to weather local regulatory headwinds that restrict or outlaw home-sharing: the top ten cities on the platform accounted for ~12% of Airbnb’s revenues in 2019 (with NYC at ~2% of revenues), and just ~7% of Airbnb’s revenues in Q2 FY21.

Overview

Through the Airbnb platform, travelers have access to roughly 5.6 million active listings, offered by more than four million hosts (“nearly 90% are individuals”) in 220 countries and regions around the world (“86% of hosts are located outside the U.S.”). For the truly adventurous among you, there are roughly 170,000 “unique homes” on the platform - you can stay in a treehouse, on your own private island, in a lighthouse, or even in an igloo.

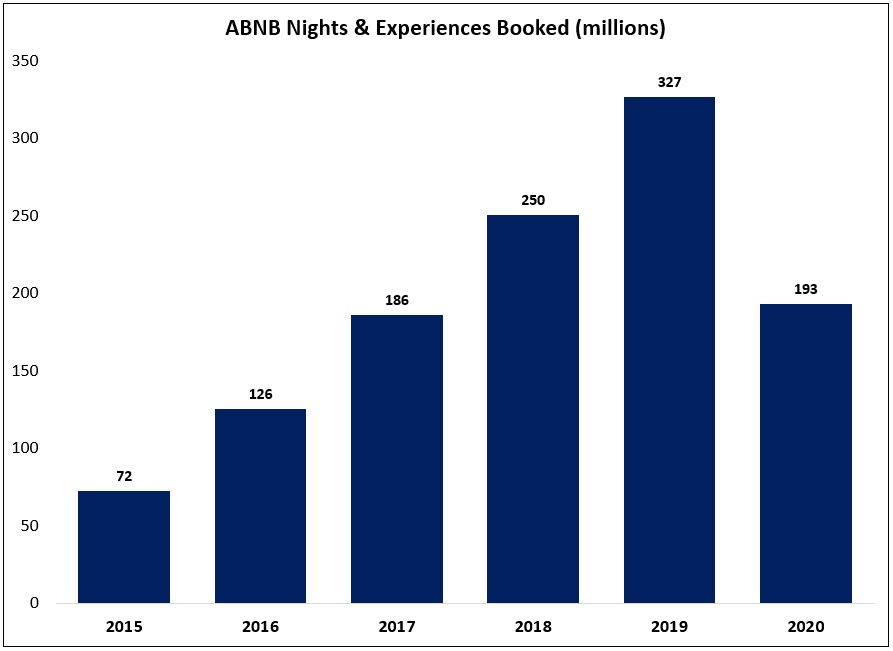

Over the past 13 years, Airbnb hosts have welcomed more than 900 million guests into their homes, with more than 50 million active users booking 327 million nights & experiences in 2019 alone (“the majority of guests who have ever made a booking on Airbnb were between the ages of 18 and 34”). As you can see, the business has reported breakneck growth: the number of nights & experiences booked on the platform more than quadrupled from 2015 to 2019.

But before we start digging into the financials, let’s start with a simple question: why do people (guests and hosts alike) use Airbnb?

Guests

I think the growth of Airbnb specifically, and alternative accommodations generally, reflects a number of developments. First, there are times when an Airbnb can be meaningfully cheaper than a hotel room, particularly in major cities (like what happened to the attendees at that San Fran conference in 2007). If you’re willing to give up some level of convenience and / or privacy, Airbnb can offer significant cost savings when traveling to tourist destinations (Q4 FY20 call: “over 40% of our nights are still urban”). Second, Airbnb’s offer a level of uniqueness that is a desirable part of the experience for certain travelers (Millennials), especially when staying outside of major metropolitan areas (“roughly 75% of listings are outside the areas where the big hotels are located”). Finally, Airbnb has an inherent adaptability given its wide range of listings that makes it easy to find accommodations that meet your exact needs (a whole house or a single room, large group or a single person, price range, length of stay, pets, special amenities like a hot tub or a gym, etc.).

Many of those comments apply to the alternative accommodations category as a whole. But why Airbnb specifically? Besides having a clear leadership position in terms of brand recognition, the past decade has given Airbnb the opportunity to secure unique inventory: as Chesky noted at Code 2018, roughly 70% of the five million homes available on the platform at that time were only listed on Airbnb.

On top of unique inventory, I’d argue Airbnb users often have a different use case than hotel customers. For example, a large percentage of Airbnb trips are for extended stays: in 1H 2021, roughly 20% of nights booked were for reservations that were at least 28 days long (and roughly 50% of nights booked were for a stay of 7+ days). In addition, a large percentage of Airbnb guest stays (“at least two-thirds”) take place outside of traditional tourist areas (not as well-served by hotel chains). While there are certainly instances where a hotel or an Airbnb are suitable alternatives, that isn’t always the case. (“We believe that the lines between travel and living are blurring, and the global pandemic has accelerated the ability to live anywhere. Our platform has proven adaptable to serve these new ways of traveling.”)

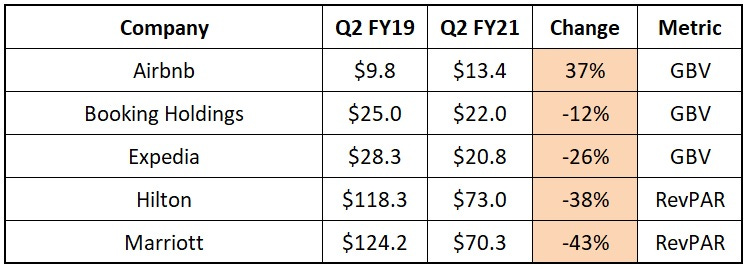

Airbnb’s “inherently adaptable” platform is the reason why domestic travel bookings rebounded strongly to double digit YoY growth by June 2020, just months into the pandemic. As you can see below, there has been a divergence in the results between Airbnb and the leading OTA’s / major hotel chains in recent periods (even on nights & experiences booked, which would exclude the impact of ADR strength / mix shift, Airbnb’s business was roughly flat vs Q2 FY19); to me, this suggests that we’re dealing with a different animal. (“Because we have millions of hosts who offer nearly all types of homes and experiences around the world, we were able to adapt to the new use cases guests wanted… Our business rebounded faster than anyone expected… as the world changes, our model is able to adapt.”).

Hosts

For hosts, the motivation to use Airbnb is clear: it offers the prospect of additional income, along with a low take rate (hosts are only directly charged a 3% fee, which basically covers payment processing costs; the low take rate benefits supply acquisition). Airbnb’s ability to attract new hosts also benefits from brand recognition, in addition to guest satisfaction on the other side of the platform (Q2 2021 call: “Over 30% of our hosts were guests first, and that number is continually increasing.”). There are other considerations that bring hosts to Airbnb: a streamlined onboarding process (“become a host in less than 10 minutes”), insurance coverages to protect hosts, and customer support and software tools to help them price, schedule, and manage their listing(s). The opportunity for hosts on the platform is evident in the results: ~50% of new hosts in 2019 received a guests booking within four days, with ~75% receiving a booking within 16 days.

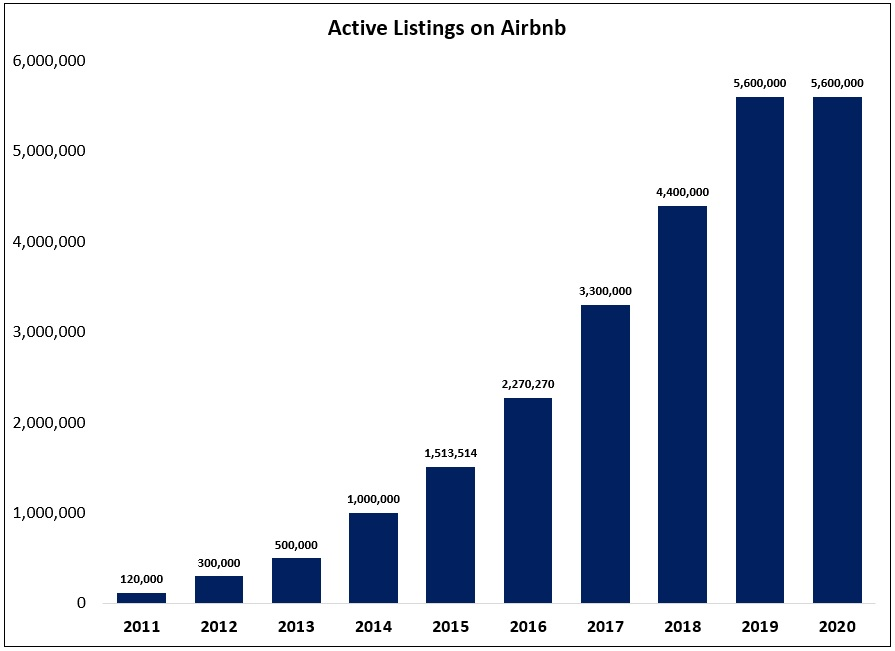

In my opinion, these are the primary reasons why the number of active listings on Airbnb has nearly quadrupled over the past five years, from 1.5 million at year end 2015 to 5.6 million at year end 2020 (naturally, the pandemic has been a headwind to onboarding new hosts).

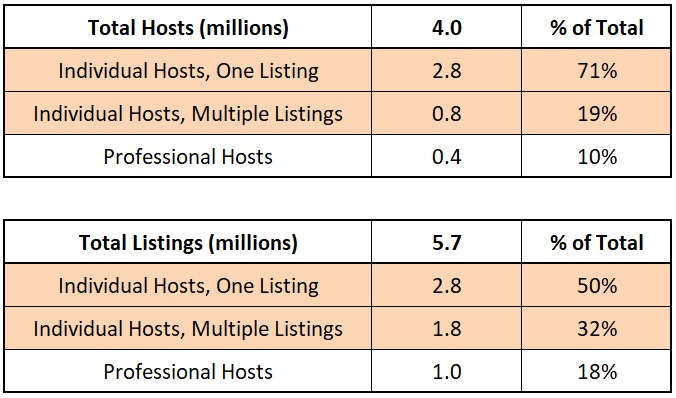

As part of this discussion, it’s helpful to breakdown some of the host data (from the S-1: “As of December 31st, 2019, 90% of our hosts were individual hosts, and 79% of those [individual] hosts had just a single listing… For individual hosts who had at least one listing in 2019, the average number of listings was 1.3.”). Based on those disclosures, we can back into a cleaner view of Airbnb’s suppliers.

As you can see, while individuals account for ~90% of all hosts, they account for ~82% of all listings (unsurprisingly, professional hosts have a higher number of listings, on average). In addition, individual hosts under index on nights booked: “As of December 31, 2019, 72% of our nights booked were with individual hosts.” In summary, despite accounting for ~10% of all hosts, professionals accounted for nearly 30% of Airbnb’s bookings as of year-end 2019.

As I think about the long-term growth and sustainability of Airbnb’s business, individual host growth is one of my main KPI’s. A large and growing number of individual hosts is what truly makes the platform unique. Notably, the GBV per average listing in 2019 was ~$7,000, which suggests that this is a supplemental source of income for many of ABNB’s individual hosts. In my mind, that conclusion offers some protection to Airbnb’s unique supply (as noted earlier, ~70% of listings are only available on Airbnb). Said differently, for the average individual Airbnb host, as long as they’re seeing activity on Airbnb, it’s not worth the headache to list their homes elsewhere (like on Vrbo). If that holds, I think it will be a meaningful long-term competitive advantage for Airbnb. (“Individual hosts are the core of our host community… OTA’s are primarily focused on professional hosts.”)

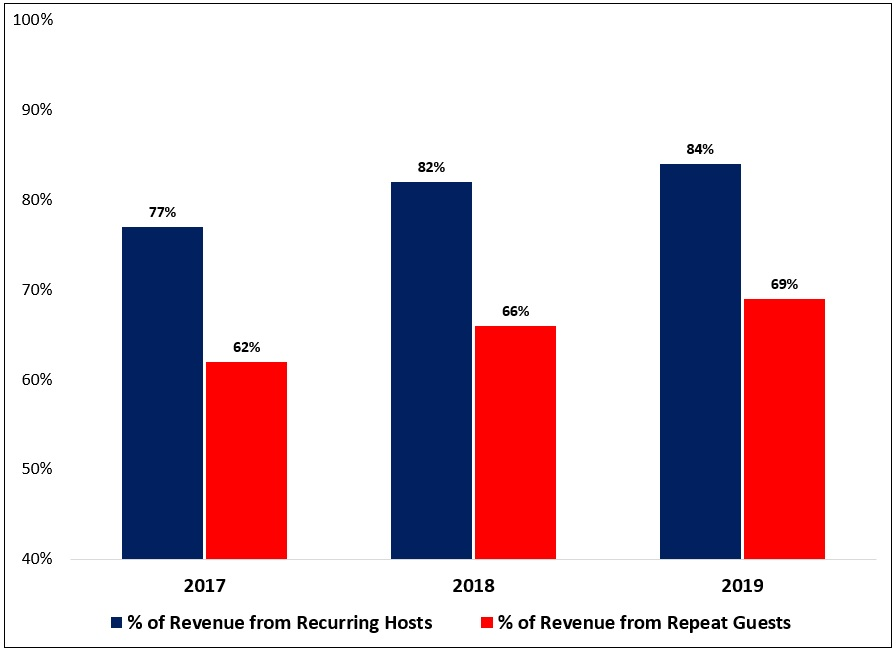

Before closing this section, I want to address a comment from CFO David Stephenson on the Q2 FY21 call. When an analyst correctly noted that the company has given limited disclosures on active listings and the number of Airbnb hosts alongside its quarterly results, he said “We’ll be talking about listings infrequently”. Personally, I think that’s nonsense. These KPI’s should be provided to the owners of the business on a quarterly basis. I’d also note that some metrics from the S-1, such as the repeat guest and recurring host data (shown below), was not included in the 2020 10-K. Again, I think this is data that should be reported to the owners of the business; if it was an important metric for the S-1, it should be disclosed in the annual filing.

Financials

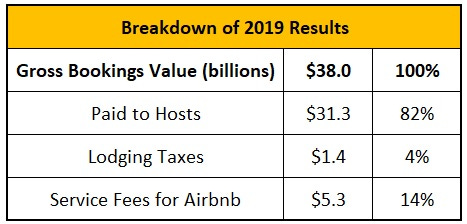

Let’s start with an illustrative example of how the funds in a transaction are distributed. Assuming a host lists their property for $100 per night, they’ll receive ~$97 from Airbnb for the booking (cleaning fees are an incremental expense determined by the host). For the guest, the price on Airbnb for that room would include a fee of ~$13 paid to Airbnb (“most guests pay a service fee that is under 14.2% of the booking subtotal…”), as well as ~$4 in lodging taxes that will be remitted to local authorities. In total, Airbnb collects ~$117 from the guest; ~$97 is paid to the host, ~$4 is paid in lodging taxes, and the other ~$16 is kept by Airbnb as its service fee (before any costs, such as payment processing). It’s also worth noting that Airbnb collects full payment from guests at the time of booking (“for the majority of bookings”), but it doesn’t send those funds to hosts until 24 hours after check-in; naturally, this results in advantageous working capital dynamics for Airbnb.

The following graphic shows a breakdown for the entirety of Airbnb’s business in 2019, which aligns with the illustrative booking discussed above.

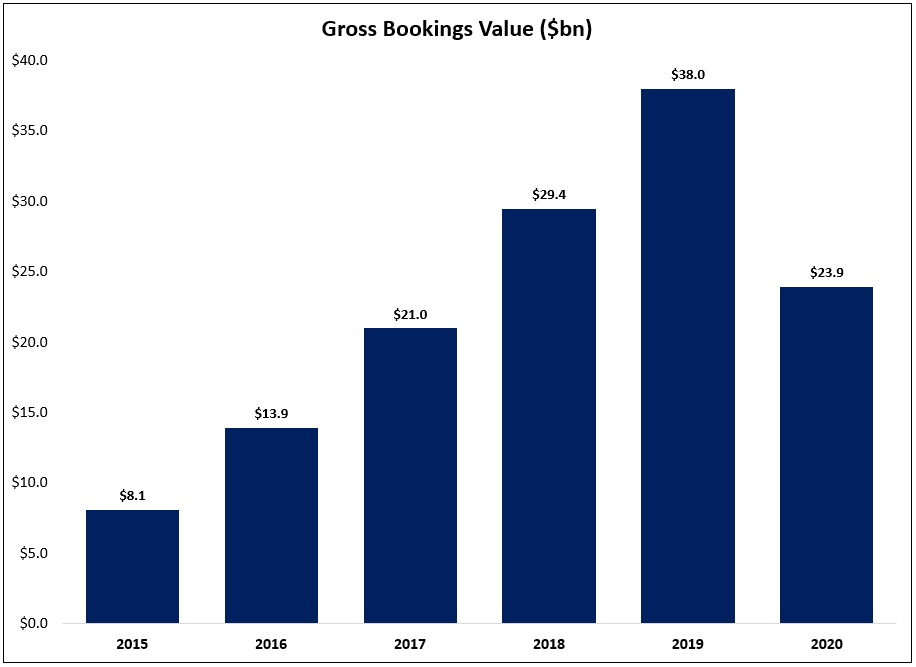

The key to Airbnb’s long-term growth is new guests (active bookers) and more highly engaged guests (higher N&E booked per guest per year). As shown below, Airbnb has experienced significant growth in recent years: 2019 GBV of $38 billion was nearly 5x higher than in 2015.

While we don’t have much historical data to work with given limited disclosures in the S-1 and the 2020 10-K, note that GBV growth from 2017 to 2019 (+81%) was entirely attributable to an increase in active bookers (from 30 million in 2017 to 54 million in 2019, or +80%). The number of nights & experiences per active booker, at roughly six per year, was unchanged over this period. I’d bet this outcome reflects an improvement in engagement among legacy users (guests), offset by mix shift towards a larger number of new Airbnb guests who are not as engaged on the platform (at least not yet). As the business matures, I think we’ll see per guest engagement improve, with the eventual roll-out of a loyalty program as well (as outlined in the previous section, ~70% of revenues in 2019 were from repeat guests).

Over the past 5+ years, Airbnb has gained a lot of ground on other travel platforms. For example, consider the 2015 – 2020 results relative to Booking Holdings (BKNG), the largest online travel agency (OTA) in the world. The below chart shows that ABNB’s GBV, as a percentage of BKNG’s GBV, has more than quadrupled over the past five years (the 2020 data requires an asterisk given how the pandemic has disproportionately affected hotel travel; that said, this outcome reflects the inherent adaptability of ABNB, which I’ve come to believe is one of the key attributes of this business).

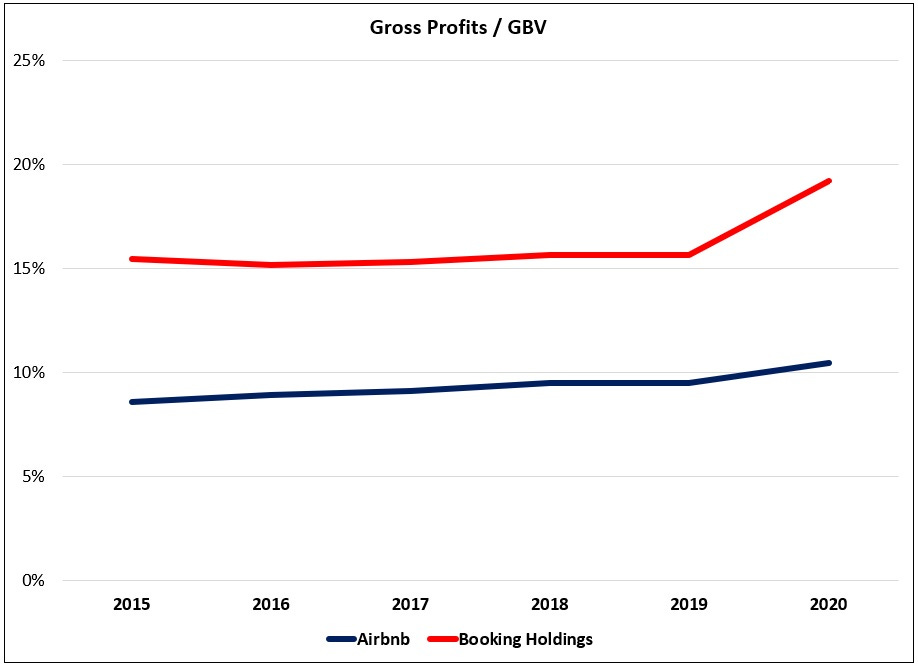

Sticking with the BKNG comparison, we start to see some notable differences in the results for these businesses as we work down the P&L. For example, gross profits as a percentage of GBV has been much higher at BKNG (roughly 500BPS annual spread, on average, over the past five years).

The net result is that Airbnb generated ~$11 in gross profits, on average, per booking over the past five years – about 40% lower than the ~$19 in gross profits per booking that BKNG generated over the same period.

Zooming out, we can see that this has a big impact on the reported results: back in 2013, when BKNG reported $39 billion in GBV (comparable to ABNB’s 2019 results), it generated $5.7 billion in gross profits. By comparison, ABNB generated $3.6 billion in gross profits in 2019. That $2.1 billion difference is the primary reason why Airbnb continues to report operating losses, while Booking Holdings has generated 30%+ EBIT margins for years (with an EBIT margin of 36% in 2013).

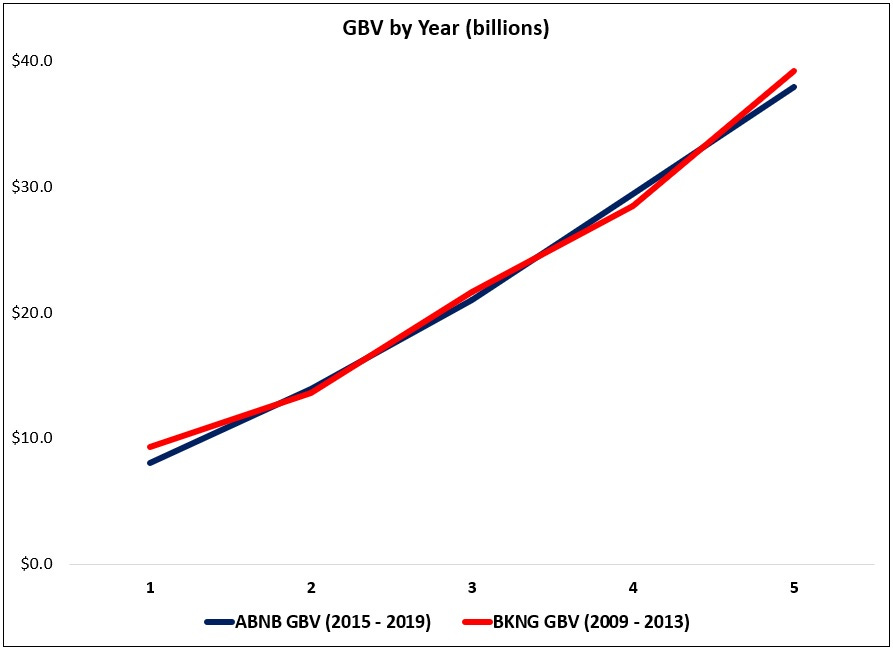

This isn’t just the cost of ABNB investing for growth (which implies BKNG wasn’t doing the same back in 2013). Interestingly, if we look at the five year period for ABNB from 2015 - 2019, and compare it to when BKNG was at a similar stage in its lifecycle (2009 – 2013), we can see that their GBV growth trajectories during these periods were nearly identical.

There are a few possible explanations for the meaningful differences in profitability at ABNB and BKNG during similar times in their lifecycle.

First, Airbnb has a lower take rate (that one is evident in the numbers).

Second, I get the sense Airbnb is an organization that did not place much emphasis on cost efficiency prior to the pandemic (more on this later). As a friend of mine put it, “BKNG is all muscle but ABNB has a lot of fat.” One benefit of Airbnb’s struggles in early 2020 is that it imparted a need for strategic focus and operating efficiency within the organization; as Chesky noted on the Q4 FY20 call, “that crisis made us much better because the first thing that happened is we got more disciplined... it was a crucible moment for the company.”

Third, I also think there’s a component of Airbnb’s platform that requires more hand holding and customer service (for both hosts and guests) than what is needed for an OTA like BKNG (where many problems are ultimately brought to the attention of the hotel). If that’s the case, I actually think you can argue that this could become a competitive advantage for Airbnb over the long run (at scale) – but it’s a headwind to profitability in the short-term.

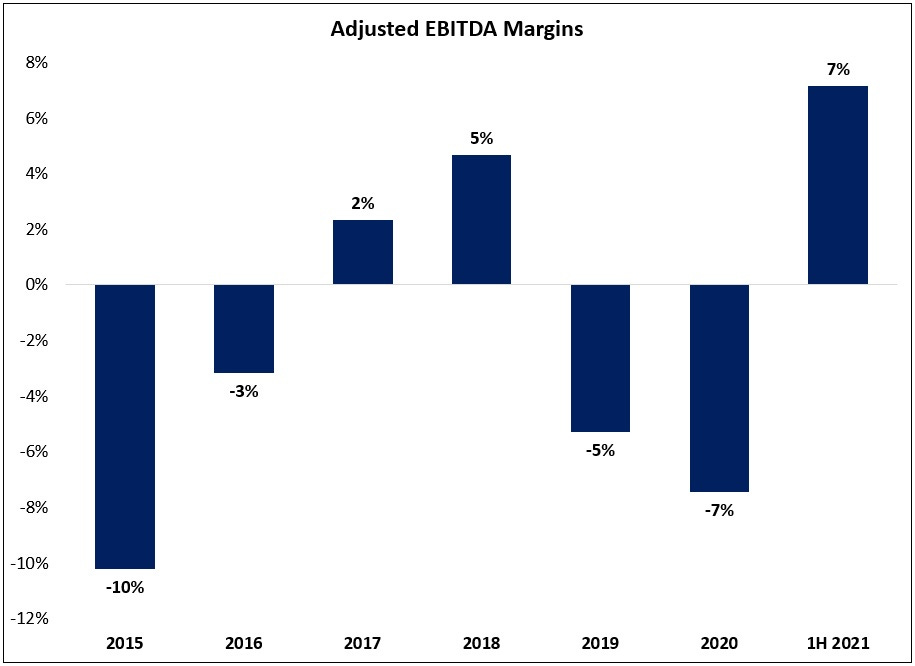

Long-term, ABNB believes they can close the EBITDA margin gap with BKNG (which lends support to the conclusion that there’s something amiss in the short-term). As noted on the Q4 FY20 call, management expects “30% EBITDA margins or greater” over time – an outcome that requires roughly 2,500 basis points of margin expansion versus their best year to date (2018). They’ve started to make some progress in 2021, with 7% EBITDA margins through the first half of the year (and with guidance suggesting they should deliver double digit margins for the full year).

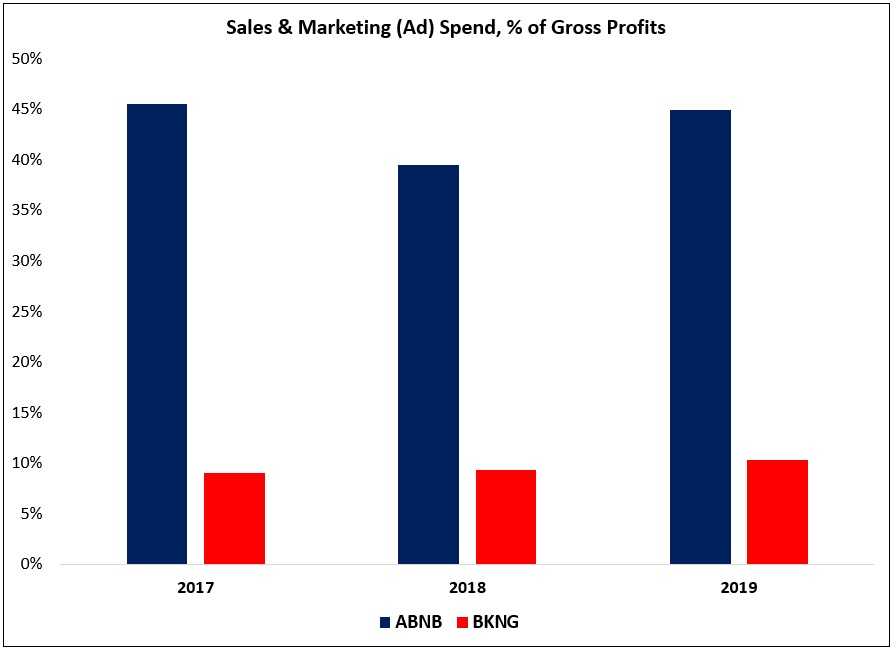

This outcome will require meaningful leverage of sales & marketing expense, which would be helped by a higher mix of organic traffic (“we expect visitor mix to shift further toward direct and unpaid channels, which represented 77% of traffic in 2019”). On the Q4 FY20 call, Chesky spoke about what he sees in the years ahead: “Even before we started resuming our marketing spend, our traffic came back to 95% of the levels of 2019… What this revealed is that our brand is inherently strong. It's a noun and a verb in pop culture. We don't intend to spend the amount (% of revenues) on marketing in the future as we did in 2019… More than 90% of our traffic was direct or unpaid, and we think that will continue in the future.”

It will almost certainly require a higher take rate as well (see the above discussion on gross profits as a percentage of GBV). At this point, I think that’s most likely to come in the form of higher guest fees; the company should be hesitant to do anything that risks host satisfaction and / or listings growth, particularly since active listings and host growth have been lackluster over the past 12-18 months. (Arun Sundararajan, author of “The Sharing Economy”: Airbnb has “the most difficult supply game I’ve ever seen”.)

New Categories

In a 2017 interview, Fortune magazine editor Leigh Gallagher, who had recently written a book about Airbnb, said the following about its co-founders:

“One of the big things they did, in terms of looking to the future, is they looked at all the tech giants from the 1990’s and saw that almost all of them were not really relevant anymore. And they thought, ‘We don’t want to be that. We don’t want to be a company that was a flash in the pan - and then 10 or 15 years later people have moved on.’ One of their lessons from that was that the best companies are in more than one category.”

As discussed in her book, Chesky, Gebbia, and Blecharczyk had their sights on some large categories: “Airbnb aims to be a platform for unique, hyperlocal activities… It wants to provide restaurant reservations, ground transportation, and soon, something involving flights.”

Over time, the CEO’s focus narrowed down to the idea of an all-inclusive, modern travel guide: “For close to two years, Magical Trips has been Chesky’s main focus, taking up one-third to one-half of his time.”

With the benefit of hindsight, I’d argue none of those new categories panned out. The lack of real traction in Experiences (an industry of independent and fragmented suppliers, without one place to easily find and book experiences online) is most notable to me because it’s an area where BKNG and TripAdvisor (TRIP) have also tried to create a new category, but ultimately with a similar outcome. Simply put, nobody in travel has really found a way to crack that nut. (Note that Airbnb introduced Online Experiences in April 2020.)

The multi-category vision that management previously held has faded (particularly for anything besides Experiences). For example, at Code 2018, Chesky disclosed Experiences was at a run rate of 1.5 million bookings a year - and he expected it to become a much larger business in the near future (“I think over the next year, you’re going to hear a lot more about them”).

Fast forward to March 2021, when Chesky said the following about the company’s response to the pandemic (Masters of Scale podcast): “Why do people want Airbnb to exist? It’s not every part of Airbnb that they want. What they want is the original thing that we did. That’s the part that we’re going to go back to. We’re getting back to the basics, back to our roots.”

The reality is that these other offerings were not generating much traction anyways (from the S-1: “Substantially all of the bookings on our platform to date have come from nights [not experiences].”). As we think about the future growth of Airbnb, I’d argue we have nothing to hang our hat on outside of the core home-sharing business that was started 14 years ago.

COVID-19

Early 2020 presented the most difficult period in Airbnb’s history.

The year started off strongly, with gross bookings in January and February climbing by more than 20% YoY. But in March and April, YoY gross bookings declined by 49% and 78%, respectively. Net of cancellations, gross bookings were less than zero during this period (the value of cancellations exceeded new bookings). This led to significant strain within Airbnb; they ultimately laid off one-third of all employees, including contractors (“dramatically cut costs that touched nearly every corner of Airbnb”). They raised $2 billion in April (“the equity portion valued Airbnb at $18 billion”), which provided the financial flexibility to help navigate the depths of the pandemic (“we were bleeding cash”); this included $250 million paid to hosts as partial compensation (25% of booking value) after Airbnb allowed guests to cancel more than $1 billion of reservations with full refunds. In hindsight, the business would go on to recover much of its lost ground within months; the company survived, and in December, Airbnb went public. That said, this period should have a lasting impact on the company; it instilled a level of focus and efficiency that was previously lacking at Airbnb.

Valuation

When Airbnb went public on December 10th, 2020, the stock opened at $146 per share – more than 100% higher than the IPO price that had been set the previous day. After a strong run over the next two months, which saw the stock top out around $217 per share, it has since fallen by more than 25% to $158 per share. On roughly 680 million fully diluted shares outstanding (from the Q1 2021 letter), the current market cap is roughly $110 billion. That’s actually a bit higher than BKNG (market cap of $95 billion) - but the noteworthy difference is that operating income for BKNG in 2019 ($5.4 billion) was higher than revenues at ABNB in 2019 ($4.8 billion).

Needless to say, Mr. Market is quite fond of Airbnb.

Conclusion

In the early days of Airbnb, the idea of sleeping in a stranger’s home seemed outlandish. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that home-sharing clearly has a place in today’s world. Airbnb has been responsible for hundreds of millions of guest stays in just the past few years, and the overwhelming majority of those visits occur without incident (in 2019, roughly 0.1% of all stays had a reported safety incident or required a Host Guarantee claim over $500).

In addition, in a world where remote work may become a new way of life, Airbnb is uniquely positioned to address the “work from anywhere” opportunity, a use case that sits between a typical hotel stay and a 12-month rental (“People aren't just traveling on Airbnb, they're living on Airbnb – and I think that's here to stay.”). If digital nomads are a new norm of the post-pandemic world, Airbnb will be key to enabling that use case (and benefit accordingly). Finally, I believe that we’ve seen a permanent shift in the willingness of travelers, particularly younger generations, to visit places that are off the beaten path, outside of the major metropolitan cities that attract visitors by the millions. That change also plays to the strengths of Airbnb.

But even if you agree on the business, what about the stock?

Frankly, I have a tough time getting close to $110 billion.

First, let’s start with GBV, which was $38 billion in 2019. Assuming that 2021 GBV comes in at around $45 billion (implies +20% vs 2019), with low 20’s annualized growth, on average, in years 2022 and beyond (compared to +38% in 2018 and +33% in 2019), GBV will reach $100 billion by 2025 or 2026. Assuming the take rate is unchanged, that would result in about $14 billion in service fees (revenues). Even if we assume significant progress on the company’s long-term financial targets, with EBIT margins climbing to 20% - 25%, that leaves us with run rate operating income of roughly $3 billion (call it $2.5 billion after-tax). Relative to today’s $110 billion market cap, which will bleed higher by a few percentage points per year even if the stock price doesn’t change as a result of significant equity issuance (SBC), I’m not so sure we’re getting a reasonable price here, even if the future looks bright. At a minimum, an investment in ABNB at today’s valuation requires a view on outsized GBV growth beyond $100 billion and / or normalized margins in excess of management’s long-term guidance. I do not feel comfortable making either of those assumptions at this time.

While I respect what the company has built over the past 14 years, and believe it will become a much larger business over the next decade, Mr. Market’s ask is a bridge too far for me. In the future, if I’m given the chance to buy this business at something closer to 20x - 30x normalized 2026e earnings (call it $50 billion to $75 billion), that would pique my interest.

For what it’s worth, I think the astounding run for the company’s stock has even surprised Chesky. During an interview with Emily Chang of Bloomberg TV in December 2020, when Chesky learned that the stock was indicated to open at more than double the IPO price, his reaction was priceless.

It seems we both agree that Mr. Market has high hopes for Airbnb.

If that optimism fades in the future, I’ll be ready to take action.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

Great analysis Alex !! I wonder how ABNB revenues will be impacted during a recession.. BKNG revenues remained impressive during 2008 crisis

Great article! Curious as to your thoughts on the take-rate differential between ABNB and BKNG? Do you think that gap will remain in the future or close (either ABNB trying to improve profitability or BKNG trying to gain share)? I agree that in a portion of ABNB's bookings they have a unique proposition but suspect that things could get quite competitive over the more mainstream listings, reducing the profit pool for both companies?