"We Sell Stuff Nobody Really Needs"

A deep dive on U.S. retailer Five Below

Five Below (FIVE) is a U.S. retailer that focuses on selling products for $5 or less to the roughly 63 million people aged 5 to 19 in the country (teens and tweens). The average Five Below carries roughly 4,000 SKU’s in a 9,000 square foot box within high-traffic shopping centers (management estimates that about half of their store traffic is attributable to customers who were in the shopping center to visit a co-tenant like TJ Maxx, Marshalls, or Ross).

Five Below meets one of my key criteria for a retailer - it’s Amazon-proof. The reason why is the nature of the transaction: the average customer spends about $150 a year at Five Below, buying ~60 items over the course of ~10 trips to the retailer. That implies six items purchased per visit for about $15 (an average cost of $2.50 per item – think novelty socks, seasonal products, art supplies, a cheap basketball, candy, etc.). I believe the company has cover from e-commerce risk due to the low-dollar value of its average transaction and the unplanned / impulsive nature of the purchase decision (“You don’t go into the store knowing you want a selfie stick, a mug in the shape of the smiling turd emoji and lip gloss”); the company’s own lackluster e-commerce efforts, at <$100 million in annual sales five years after launch, speaks to this reality (“shipping often costs more than the entire purchase”).

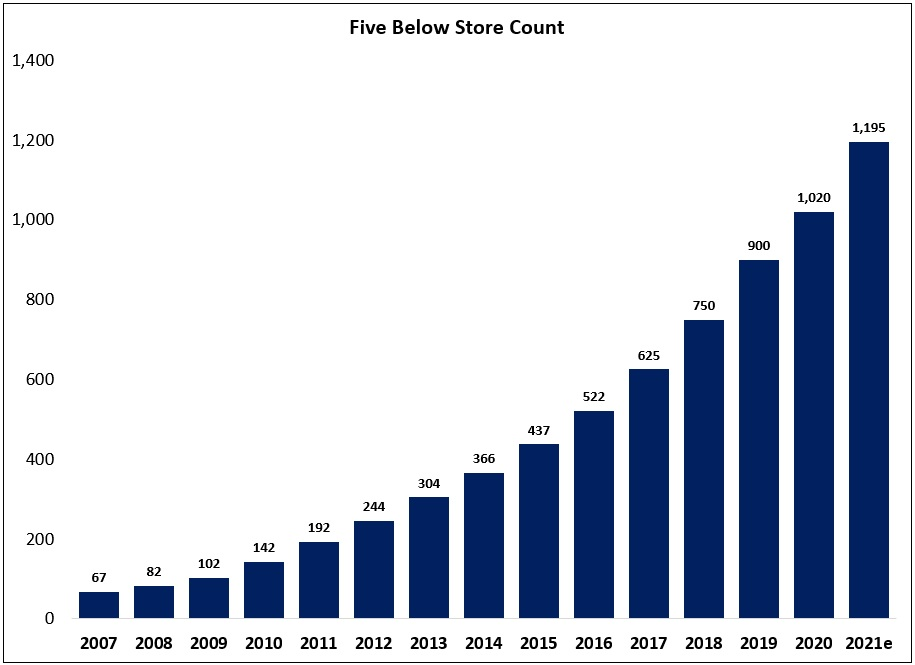

This is still a relatively new concept: Five Below opened its first store near Philadelphia in 2002 (IPO in July 2012). Over the course of the next 18 years, the footprint expanded to more than 1,000 locations across 38 states, with plans to add another 170 - 180 stores throughout 2021 (funded through retained earnings; the company ended FY20 with $410 million in cash on its balance sheet and no debt). Long-term, management believes there’s an opportunity for more than 2,500 Five Below stores in the United States.

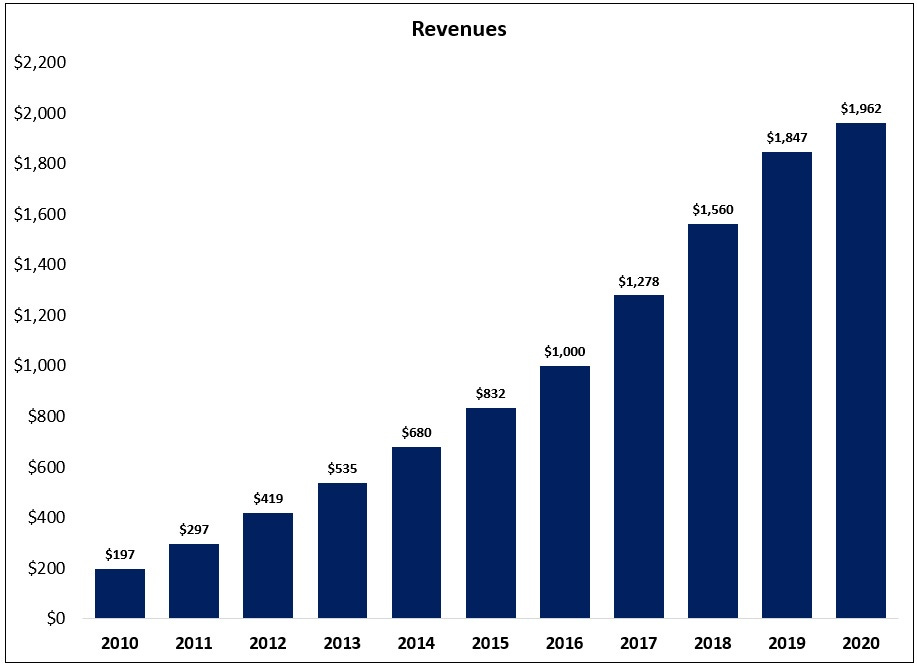

Revenues have followed suit: over the past decade, Five Below’s annual revenues have increased ten-fold to nearly $2 billion a year (26% CAGR).

In 2019, co-founder Thomas Vellios spoke about the original business plan:

“We knew there was a ton of money being spent by this universe of kids, but nobody was really creating something new… You had about $24 billion being spent in the toy sector every year. But then we realized that kids, by the time they got to the age of 5 or 6, we’re exiting the toy stores… toy stores didn’t evolve. So, once you got to that age, you no longer stayed in toy stores… And the biggest toy store in America [Toys R Us] never really figured out how to sell to kids. It was the most unfriendly store… some bike or some big box from 12 feet up could fall and crush you. So, that was a good thing for us.

Then we looked at kids aged 13, 14, and over… all going to the mall, “mall rats”. And then there was a segment in the middle… “tweens”, nobody really went after that segment. Affordability was key if you wanted to create a business that was universal in appeal. It didn’t matter how much money you had; you were able to afford Five Below. We looked at dollar stores, but we really didn’t like them for kids – yes, you go there and you shop, but they were dirty (at least at the time)… they were more of a needs based store, you bought a roll of Charmin toilet paper for $1. That wasn’t our gig.

So, we wanted to recreate a store that was magical to me growing up when I came to the U.S. In those days, they had stores called five and dimes… was there a space to create a new approach to a modern day five and dime? A store kids would call their own. But, at the same time, that moms would approve… When we looked at the dollars spent in a given year for this group – both by the kids and the parents – it was in excess of $200 billion.

So, needless to say, the landscape was ripe for disruption.”

That business plan and target audience led to a number of “must haves” for Five Below. First, the assortment had to be “trend right” (as Mr. Vellios notes, “we sell discretionary goods; in layman terms, we sell stuff nobody really needs – and we want you to buy it all the time”). Second, unlike the towering racks of bikes and boxes at Toys R Us, Five Below aspired to create a store environment that was attractive to its target customer (“easy to navigate, sight lines across the entire store, cool and vibrant colors, great music playing”). And third, product affordability was a major focus for the founders - and when your core shopper relies on a $20 weekly allowance from their parents as their sole source of “income”, that meant selling products for $5 or less.

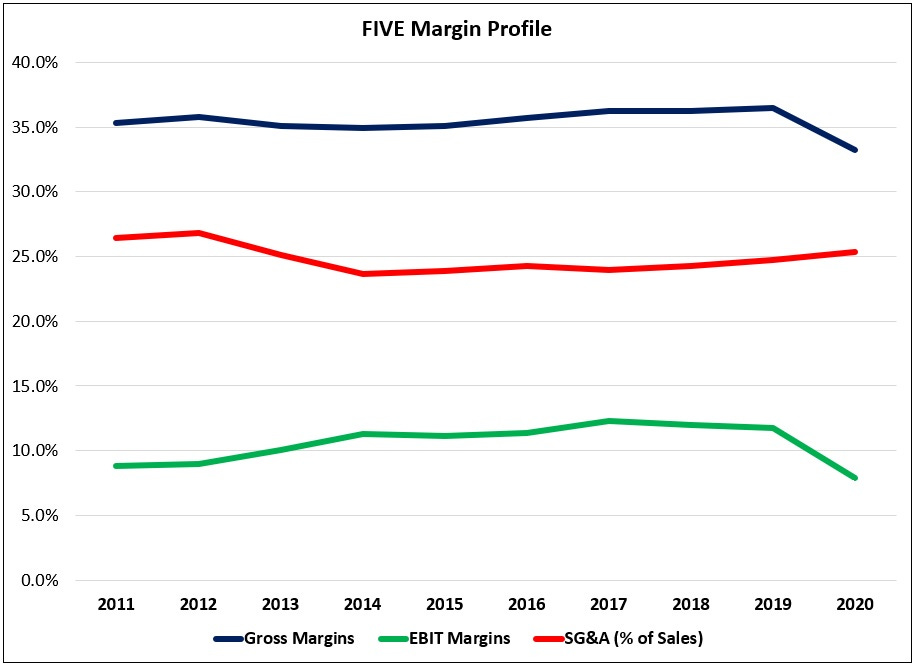

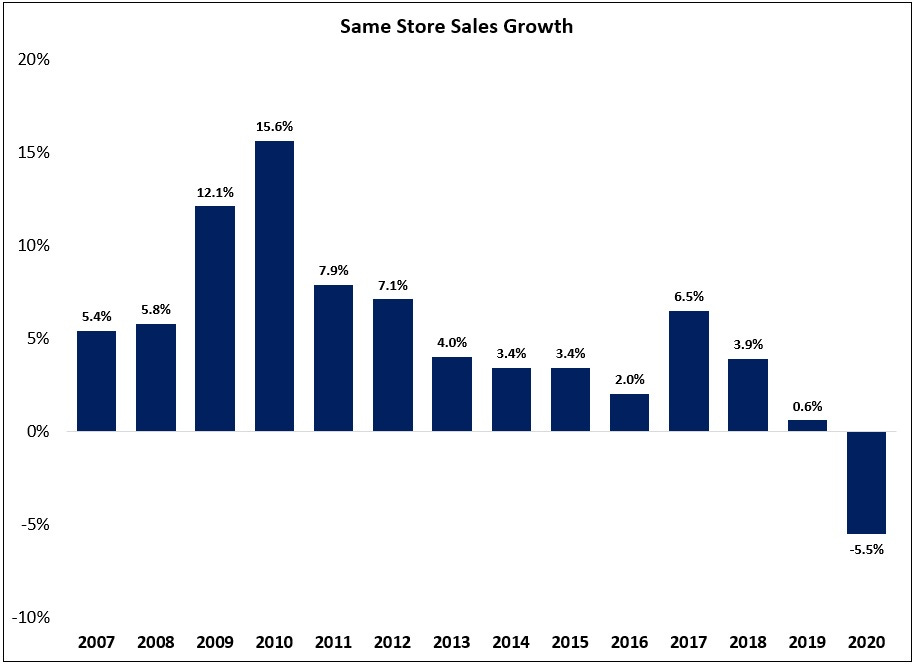

Despite a growing store base, unit economics have continued to improve over the years: as shown below, the average Five Below generated roughly $2.2 million in revenues in 2019 – about 40% higher than at the start of the decade (the company faced pandemic-related headwinds in 1H 2020, including the closure of all stores throughout most of March and April).

In addition, the unit economics are very attractive: using 2017 - 2019 average EBIT margins of ~12% (shown below), a typical Five Below generates about $265,000 in operating income per year. To put that number into context, the average Dollar Tree - another retail banner that I’m a fan of - generates about $220,000 in operating income on $1.7 million in sales (~13% margin).

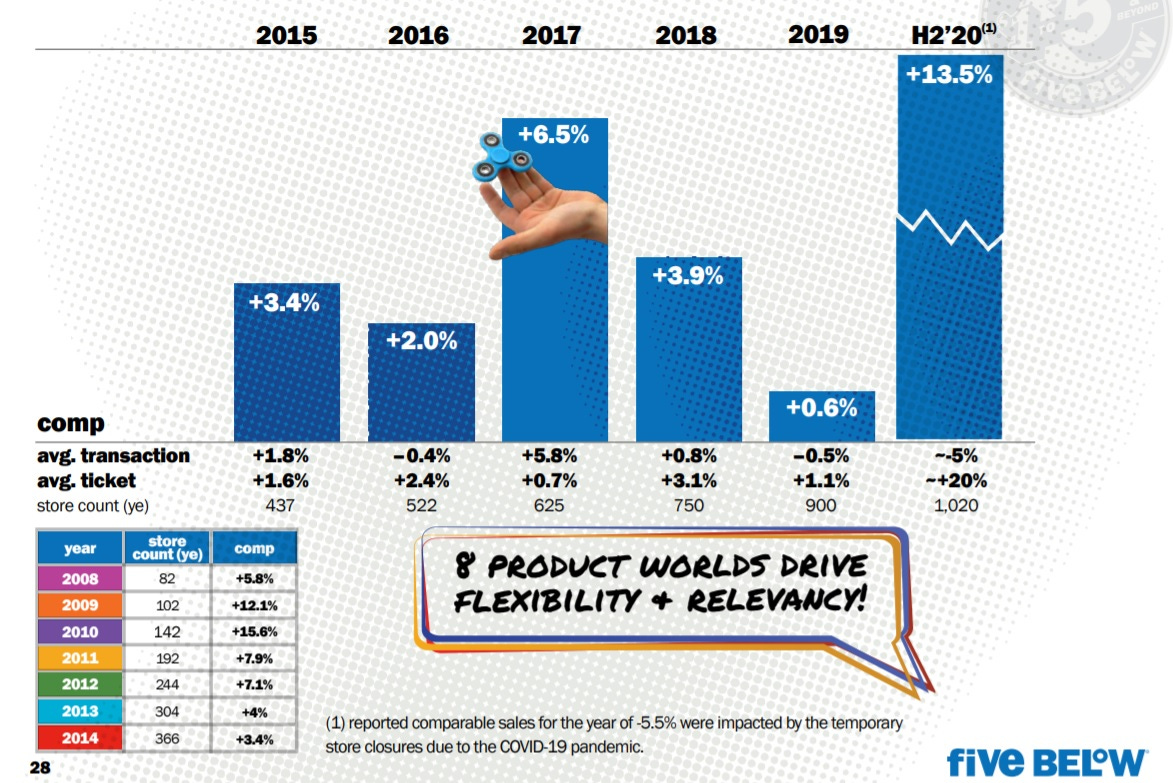

If there’s anything that concerns me in the recent results, it’s traffic trends. For example, in Q4 FY19 (the holiday Q typically accounts for 35% - 40% of FIVE’s annual sales), comps declined by more than 2% due to a nearly 4% drop in comp transactions (this wasn’t a major focus at the time: when the company reported the Q4 FY19 result on March 18th, 2020, they had just announced that they would temporarily close all locations as a result of the pandemic). That weakness in comp transactions has been relatively persistent: as shown below, the company reported a single year of 1%+ comp transactions growth in the four years from 2016 - 2019. As we look ahead, if cannibalization has a larger impact on results and / or if the growth in average ticket subsides, FIVE will struggle to keep SSS in positive territory (“most of our near-term growth will occur within our existing markets”). Note that this is a longer term comment; in the short-term, I expect to see continued trip consolidation, as has been the case across most of retail.

Despite the markets initial reaction, with the stock falling ~60% in the early months of 2020, COVID has proven to be a tailwind for Five Below (at least in the short-term): in Q1 FY21, same store sales were +23% for the subset of ~750 stores that were open in Q1 FY19 (pre-COVID comp). If that trend holds, we’ll see a sizable step-up in per store revenues for FY21 (even a 10% increase from FY19 would push the average to about $2.5 million per box).

Over the years, there have been periodic worries about FIVE’s exposure to trendy products (most notably fidget spinners in 2017). I think that misses the forest for the trees. Part of Five Below’s business model is spotting these trends reasonably early and then effectively merchandising against them to stimulate demand (that includes ensuring they don’t get stuck with millions of dollars in worthless inventory as the trend fades). I think Five Below remains well positioned to keep playing – and winning – at that game.

Conclusion

The significant growth that Five Below has reported over the past 18 years speaks to the opportunity – and risk – associated with retailers. The company has been able to expand at a feverish pace through the use of operating leases and by minimizing the cost of unit growth (average net new store investment of about $300,000). When that goes well, it can result in massive winners: Peter Lynch used the “regional to national” playbook often throughout his career, with companies like Taco Bell, Dunkin’ Donuts, Toys R Us, Cracker Barrel, Walmart, and Home Depot. (Lynch in Beating The Street: “The very homogeneity of taste in food and fashion that makes for a dull culture also makes fortunes for owners of retail companies... What sells in one town is almost guaranteed to sell in another, as it has with donuts, soft drinks, hamburgers, videos, nursing-home policies, socks, pants, dresses, gardening tools, yogurt, and funeral arrangements.”)

On the flip side, if things start to go poorly, the company will be saddled with hundreds of boxes in unattractive locations (FIVE: “~5% of stores located in malls”). Think about banners like KB Toys, Toys R Us (note that it was also mentioned above as a winner), Office Max, Borders, GameStop, Zany Brainy (founded by the same guys who started FIVE; the 187-store chain filed for Chapter 11 in 2001)… and the list goes on and on. They put up years, and for some even decades, of strong sales and EPS growth due to SSS growth and footprint expansion. But when those levers start to break, it can get ugly.

Said differently, for the truly long-term investor, owning a company like Five Below requires real conviction in the long-term sustainability of the concept. For FIVE, I believe that this will require consistent execution around the “must haves” discussed earlier (“trend right”, fresh and unique product assortment, attractive store environment for the target customer, and affordability / value).

To date, I’d argue Five Below has done a great job navigating this risk: revenues per average store continue to climb (as noted earlier, +40% from 2010 to 2019), and they’ve only needed to close five stores since the start of FY16 (they’ve opened 500+ stores over the same period).

The problem, as is often the case with growthier names, is the current valuation: since bottoming in March 2020 around $52 per share, the stock price has increased by ~270% (to $194 per share). Relative to peak results - EPS of $3.1 per share in FY19 - it trades at roughly 63x earnings.

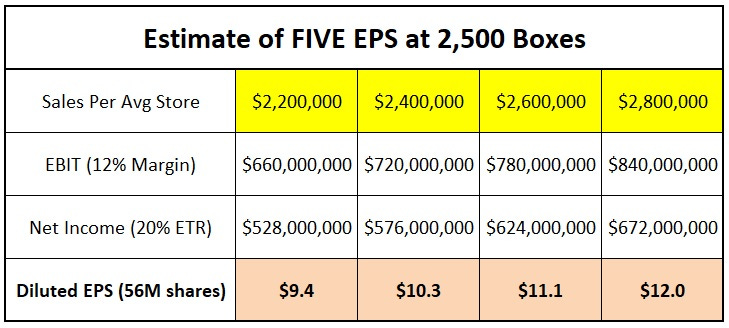

What will this look like at maturity? Here’s what profitability (EPS) looks like at different levels of per store revenues on 2,500 units (assumes 12% EBIT margins, a 20% effective tax rate, and an unchanged share count).

At $2.6 million per box, Mr. Market is willing to pay 17x - 18x 2028e earnings for FIVE (that assumes 180 – 200 net new stores per year from 2021 - 2028). And then what? Is 2,500 stores the end for Five Below?

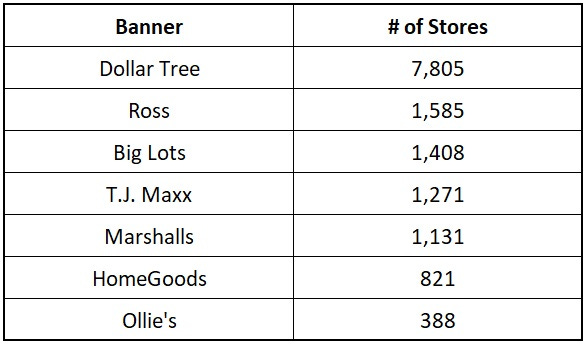

A look at the year-end 2020 store count for a couple of other U.S. retailers may be instructive (in all honesty, I’m not sure which of these banners, if any, can be considered a good comp for Five Below).

In summary, I’m actually more confident on the future of this business than I expected to be when I first started digging in. The fact that they’ve put up strong operating results for 15+ years, and have continued to do so while adding ~500 net new units over the past 48 months, is impressive.

That said, the current valuation is a bridge too far for me. I also need more time to think about the key variables to the long-term thesis (the likelihood of 2,500+ U.S. stores, international growth opportunities, etc.). Over time, particularly if we get some help from Mr. Market on the stock price, I’ll revisit the Five Below story (and when that happens you’ll be the first to know).

Until then, I plan on watching from the sidelines.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.