TKO: Positioned To Capitalize

A deep dive on WWE / TKO and EDR

While mixed martial arts (MMA), and specifically the UFC, has become a global phenomenon, the sport was in a very different place 22 years ago.

At that time, Dana White ran three gyms in Las Vegas and represented a handful of fighters. One day, during a contract negotiation with UFC owner Bob Meyrowitz, it was made clear to White that the league’s days were numbered: “There is no more f-ing money; I don’t know if I have enough money to put on another event.” A reasonable response by White may have been to call it quits and to start looking for a new career; instead, he sensed an opportunity. He called Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, his friends who were well off financially after inheriting their father’s casino business in the 1990’s. White told the Fertitta’s that he thought they should make Meyrowitz an offer: “The UFC is in trouble; I think we can buy it and I think we should.” The Fertitta’s agreed; shortly after, in 2001, they acquired the UFC for $2 million (White was named President of the company and given ~10% of the equity).

The UFC struggled for the next few years, with cumulative losses of more than $40 million by the end of 2004 - but their fortunes turned in 2005 with the first season of “The Ultimate Fighter”, a reality show that aired on Spike (at that time, a TV channel that was targeted to young men). The idea, as explained by a former producer for the show, was to introduce the combat sport to a more general audience, “to legitimize it”. The plan worked: “The Ultimate Fighter” began the process of turning the UFC from a niche combat league into a mainstream and global asset (TUF is now on its 31st season).

This is where Ariel (Ari) Emanuel, the CEO of talent representation agency Endeavor (EDR), comes into the picture: “We came up with a research department to look at TV ratings, which helped us sign people and to get shows on the air… This guy comes in and says, ‘Here’s the number [for “The Ultimate Fighter”] on Spike’, and I went, ‘Holy cow’.” Emanuel eventually signed Dana White as an Endeavor client, which ultimately led to a major development in their collective stories: in 2016, EDR (which by then included William Morris and IMG) acquired a majority stake in the UFC at a valuation of ~$4 billion. Endeavor purchased the remaining 49.9% ownership stake of the UFC from KKR and Silver Lake in April 2021, which was funded from its IPO proceeds and a separate private placement (this followed an ill-fated attempt to go public in 2019). Two years after the IPO, in April 2023, EDR announced its next big deal: the UFC would merge with the WWE into a new publicly traded company (ticker “TKO”). Endeavor will own a 51% controlling interest in TKO, with the remaining 49% held by WWE shareholders (stock-for-stock deal, expected to close in late 2023).

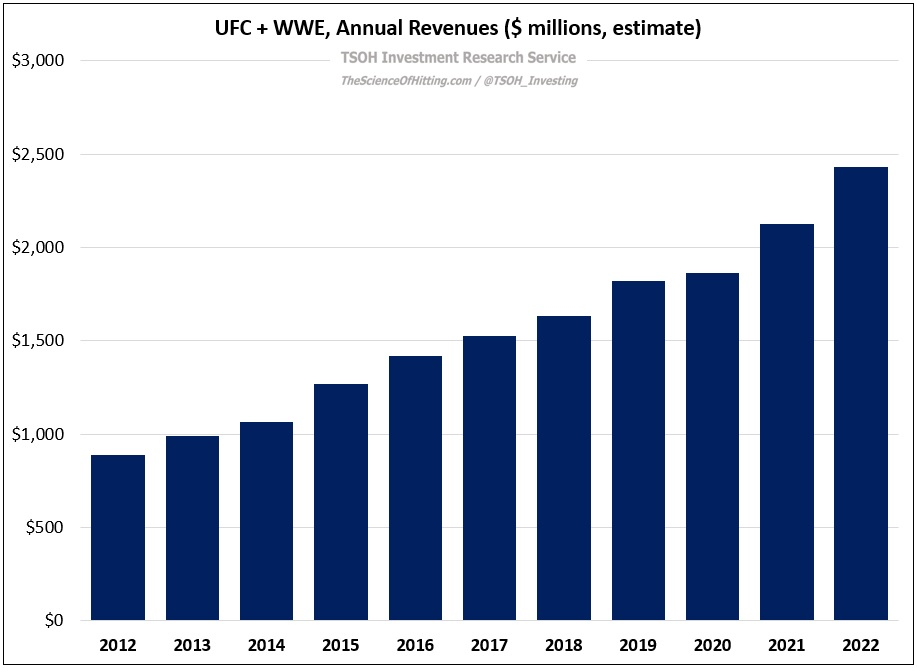

In summary, TKO’s value will be solely attributable to its ownership of the UFC and the WWE. While that’s largely true for Endeavor / EDR (the vast majority of its intrinsic value), it still owns other businesses and assets that are worth a few billion dollars (more on this later). The primary question to answer - for EDR and TKO - is the long-term value of the UFC and the WWE.

The U.S. Media Landscape

In 2011, the UFC reached a seven-year media rights agreement with Fox (“The Sports Business Daily Journal reported the bidding reached an average of $100 million a year”). When that deal ran its course, the UFC found a new home: ESPN. In 2018, the companies announced a five-year deal with a reported value of ~$1.5 billion (~$300 million per year). Shortly after, in 2019, the UFC and ESPN announced that the agreement had been expanded to include exclusive distribution of pay-per-view (PPV) rights through ESPN+, alongside a two-year extension of the agreement. In total, the UFC and ESPN have a deal for ~$450 million per year (AAV) through 2025.

The WWE has domestic rights deals with two partners: Fox and NBCU (Comcast). The linear TV contracts, which run through October 2024, are for ~$205 million per year with Fox (“Friday Night Smackdown”) and for ~$265 million per year with NBCU (“Monday Night Raw” and “NXT”). In addition, the WWE has a five-year streaming deal through early 2026 for premium live events on Peacock for ~$200 million a year. (Former NBCU CEO Jeff Shell: “We’ll continue to be aggressive in looking for sports rights; not only whether we can get them for a price that we think we can get a return on, but also properties where we can drive linear and digital usage… WWE is kind of the perfect deal for us; we took a franchise that was already important to us on linear and extended it to Peacock in a way that’s been very successful.”)

To put these WWE numbers in context ($205 million + $265 million + $200 million = $670 million annually for U.S. distribution rights), we can guesstimate that the domestic rights generated ~$100 million before the mid-2014 renewals. (May 2015: “In 2014, the WWE generated about $180 million by licensing its core content, primarily Raw and SmackDown, to networks around the world within the pay ecosystem. Seven of those deals - in the US, the UK, Canada, India, Thailand, Mexico and Latin America - represent about $130 million of the $180 million.”) Clearly, the WWE has successfully negotiated much improved agreements over the past decade.

A big question for the UFC and the WWE is how the continued decline of pay-TV in the United States may impact their long-term economics. With millions of households cutting the cord each year (with no signs of slowing), are we nearing a breaking point? Will Disney, Comcast, and Fox be willing and able to cut larger checks to the leagues at the next round of negotiations?