"There Aren't Many See's Candies"

“Through watching See’s, I gained a business education about the value of powerful brands that opened my eyes to many other profitable investments.”

- Warren Buffett (“Berkshire – Past, Present, and Future”)

In the late months of 1971, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger learned that See’s Candies, a West Coast manufacturer and retailer of boxed-chocolates, was on the selling block. The sellers wanted $30 million for the business (after accounting for $10 million of cash on the company’s balance sheet), and Munger thought that was a reasonable price given its competitive position: “See’s has a name that nobody can get near in California… It’s impossible to compete with that brand without spending all kinds of money.” But despite Munger’s enthusiasm, Buffett concluded that he wasn’t willing to pay a penny more than $25 million for the business, a price that implied a low double digit multiple of See’s after-tax earnings (“three times net tangible assets made me gulp”). Thankfully, the owners were willing to compromise, and the acquisition was completed in January 1972 (See’s was purchased by Blue Chip, which became 100% owned by Berkshire in 1983).

As Buffett told Alice Schroeder, the key insight that convinced the duo to buy See’s was their belief that its products were underpriced: “We thought it had uncapped pricing power. See’s was selling candy for about the same price as Russell Stover… You were buying something that perhaps could earn $6.5 or $7.0 million [after-tax earnings] if just priced a little more aggressively.”

See’s brand positioning was cultivated over decades by consistently delivering on its customer promise: candy prepared with the finest quality ingredients (“See’s Quality”). As with any brand, some of this was surely intangible; it was an accumulated belief / affection among a group of customers that may not be attributable to an identifiable characteristic of the brand or its product(s). As Buffett wrote in a 1972 letter to See’s President Chuck Huggins, “Maybe grapes from one little eighty-acre vineyard in France are really the best in the whole world, but I have always had a suspicion that about 99% of it is in the telling and about 1% is in the drinking.”

See’s, which opened its first candy store in Los Angeles in 1921, established such a position with Californians (as disclosed in the 1991 letter, the state still accounted for nearly 80% of the company’s revenues at that time). Given the nature of demand within the specialty candy / boxed chocolates category – low per-capita consumption (about one pound per year in the U.S.), with purchases typically made around special occasions like Christmas, Easter, and Valentine’s Day – you can appreciate how the See’s brand, if maintained and strengthened over the long run, could be a considerable advantage.

On See’s brand image, we shouldn’t overlook the work that led to that perception: it was built over decades by earning it (consistently reinforcing that image). Famously, during World War II, when rationing would’ve required See’s to dilute its recipes to satisfy customer demand, the company put a sign on its doors: “Sold Out. Fresh Candies Dec. 27th. Give War Bonds for Christmas.” In addition to using the finest ingredients, See’s was adamant about controlling production and distribution (retail); as Buffett noted to Huggins (1972), “We have always maintained an incredibly pure approach to distribution, which undoubtedly contributes substantially to the public’s image of our product.” (This differed from brands like Russell Stover, which were available at grocery stores, drug stores, etc.)

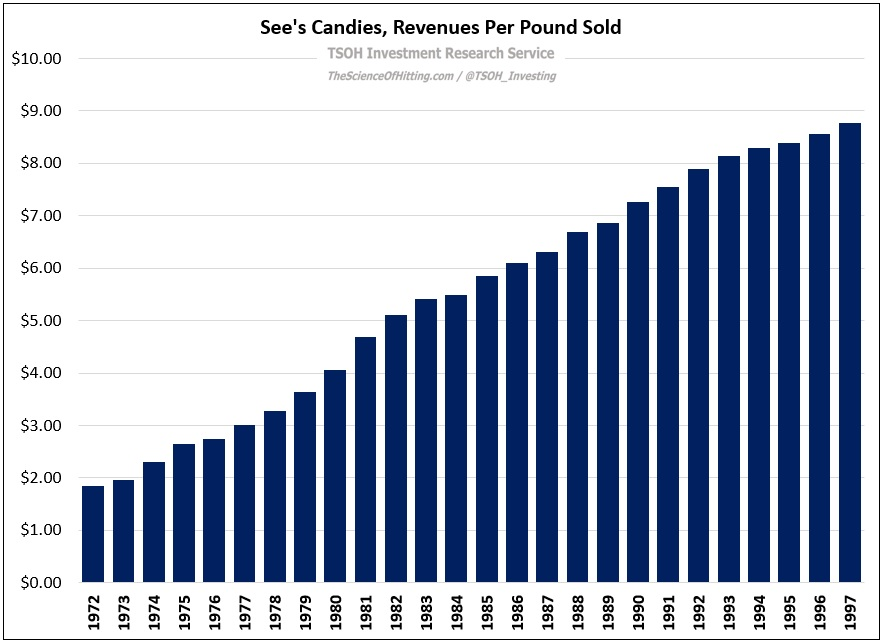

The takeaway is that Buffett and Munger held the view, based on the brand equity See’s had established over half a century with millions of consumers in California, that the company had significant untapped pricing power – and as the chart below shows, they put that belief to the test over the next quarter century. As you can see, revenues per pound of candy sold increased more than four-fold from 1972 to 1997, from $1.85 per pound to $8.80 per pound. (In addition to periodic mentions in Buffett’s shareholder letters, revenue and profitability for See’s Candies was broken out in Berkshire Hathaway’s annual reports until 1999; that ended in 2000, when the company was consolidated into the Manufacturing, Retailing, and Services segment.)

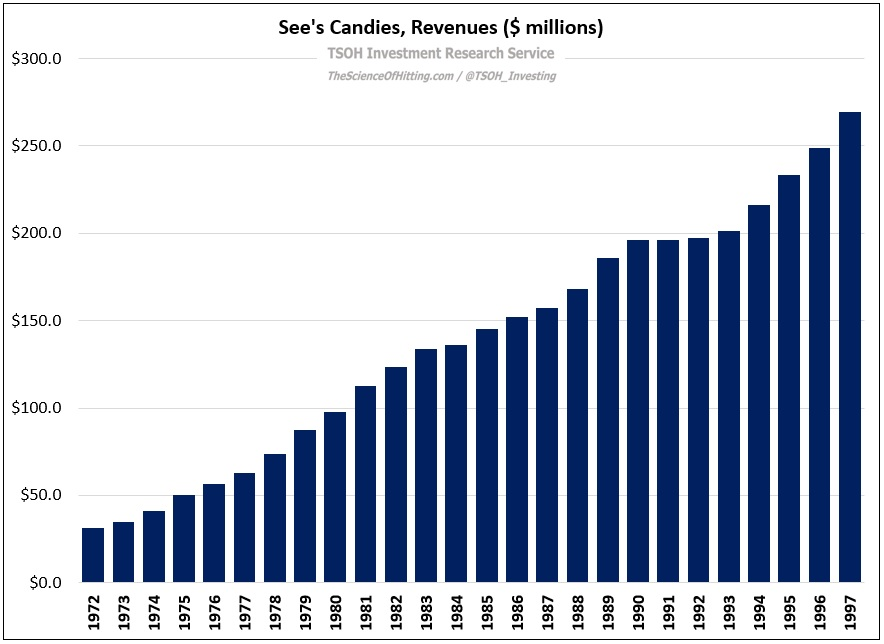

Throughout this 25-year period, volumes only increased ~2% per year (from ~17 million pounds in 1972 to ~31 million pounds in 1997). Despite that lackluster volume growth, revenues increased ~9x over this period, from ~$31 million in 1972 to ~$269 million in 1997 (25-year CAGR of +9% p.a.). The difference between the two figures reflects the mid-single digit annualized price increases (per pound sold) that See’s commanded from consumers.

This volume / price mix also had an outsized impact on profitability: by the mid-1990’s, See’s was reporting low-20’s (%) pre-tax profit margins, a meaningful improvement from the low double digit margins reported in the early 1970’s. As a result, pre-tax profits increased ~14x (+11% CAGR), from ~$4 million in 1972 to ~$59 million in 1997. (By 1977, five years after the deal was finalized, See’s annual pre-tax income had tripled to ~$13 million.)

An important consideration during this period was the impact of inflation, which averaged ~5.5% per year from 1972 to 1997 (on the price per pound discussed earlier, $1.85 in 1972 was equivalent to about $7 in 1997). Said differently, inflation chewed away at a very significant percentage of the nominal price increases reported over this period. But importantly, as Buffett discussed in the 2007 letter, See’s required a minimal amount of incremental capital to support its growth, which meant the vast majority of these nominal dollars were ultimately retained by Berkshire Hathaway:

“The capital then required to conduct the business [in 1972] was $8 million… Last year See’s sales were $383 million, and pre-tax profits were $82 million. The capital now required to run the business is $40 million. This means we have had to reinvest only $32 million since 1972 to handle the modest physical growth – and somewhat immodest financial growth – of the business… All of that, except for the $32 million, has been sent to Berkshire (or, in the early years, to Blue Chip)… Just as Adam and Eve kick-started an activity that led to six billion humans, See’s has given birth to multiple new streams of cash for us. (The biblical command to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ is one we take seriously at Berkshire.) There aren’t many See’s in Corporate America. Typically, companies that increase their earnings from $5 million to $82 million require, say, $400 million or so of capital investment to finance their growth. That’s because growing businesses have both working capital needs that increase in proportion to sales growth and significant requirements for fixed asset investments. A company that needs large increases in capital to engender its growth may well prove to be a satisfactory investment. There is, to follow through on our example, nothing shabby about earning $82 million pre-tax on $400 million of net tangible assets. But that equation for the owner is vastly different from the See’s situation. It’s far better to have an ever-increasing stream of earnings with virtually no major capital requirements.”

What made See’s a great business, and a home run acquisition by Buffett and Munger, was the combination of these factors (if See’s had been a standalone public company, that ~11% pre-tax income CAGR would’ve resulted in significantly higher TSR’s given their ability to return the excess capital to shareholders in the form of dividends and / or repurchases).

As noted at the outset, See’s Candies taught Buffett and Munger about the value of “powerful brands”, an insight that would pay further dividends for Berkshire Hathaway over time; as Buffett noted at the 1997 shareholder meeting, “If we hadn’t bought See’s, with some subsequent developments after that made us aware of other things, we wouldn’t have bought Coca-Cola in 1988; you can give See’s Candies a significant part of the credit for the $11 billion-plus profit we’ve got in Coca-Cola at the present time.”

See’s Valuation

With the disclosures provided by Berkshire over the first ~30 years, along with some digging through Buffett’s more recent comments, I’ve built a financial model for See’s over the past 50 years (1972 – 2021); with the benefit of hindsight, what was See’s worth when they bought it?