"The Right Way To Run An Insurance Company"

National Indemnity: "Just A Little Different"

In 1967, Warren Buffett wrote the following in his letter to partners:

“Berkshire Hathaway [B-H] is experiencing and faces real difficulties in the textile business. While I don’t presently foresee any loss in underlying values, I similarly see no prospect for a good return on the assets employed in the textile business.”

As Alice Schroder recounted in “The Snowball”, Buffett had come to the conclusion that “his most important task that year [1967] was to find something new which he could hitch the broken-down nag of Berkshire to before its ‘substantial drag’ on his performance became intolerable.”

One potential answer Buffett had kept an eye on for a number of years involved Charlie Heider, a friend and board member of National Indemnity, which was headquartered a few blocks from Buffett’s office in Omaha (National Indemnity was a property-casualty insurer that specialized in commercial auto and general liability insurance). Buffett and Heider had previously discussed the company, with particular emphasis on one notable peculiarity about its CEO, Jack Ringwalt: “For fifteen minutes every year, Jack would want to sell National Indemnity. Something would make him mad. Some claim would come in that irritated him… So Charlie and I discussed the phenomenon of Jack being in heat once a year for fifteen minutes. I told Charlie if he ever caught Jack in this particular phase to let me know.”

When Heider called in February 1967, Buffett was ready to act; he asked Ringwalt how much he wanted for National Indemnity, and the price was substantially higher than expected (Jack wanted $50 per share, “$15 per share more than Warren thought it was worth”). But Buffett paid up to get the deal completed – and with that, Berkshire Hathaway’s expansion into the insurance business began (the cost of the acquisition was $8.6 million).

25 Years At National Indemnity

Fast forward to the 2004 Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meeting, nearly four decades after the National Indemnity deal was finalized. During the meeting, as well as in that year’s shareholder letter, Buffett discussed the financial results from National Indemnity over the prior quarter century.

The first set of data, shown below, is National Indemnity’s annual written premiums. As you can see, the volume of business in any given year was very volatile. After declining for a few years in the early 1980’s, written premiums increased six-fold in two years, from ~$62 million in 1984 to ~$366 million in 1986 (as Buffett wrote in the 1986 letter, “The trends in National Indemnity’s traditional business… suggest how gun-shy other insurers became for a while”). Over the next 13 years, National Indemnity’s written premiums reported a cumulative decline of roughly 85%, from ~$366 million in 1986 to ~$55 million in 1999; this was a period of seemingly unending headwinds for National Indemnity, with YoY premiums declining in 11 of those 13 years. Finally, in 2000, fortunes reversed once again: in 2004, five years after its volumes had bottomed, National Indemnity’s written premiums exceeded $600 million - up more than 10x from the 1999 lows.

This outcome was by design; at National Indemnity, sound underwriting was the primary goal, not premiums growth. Of course, that isn’t a novel idea: every insurer wants to have sensible underwriting. But that objective, at times, can clash with the interest of key stakeholders - for example, the insurer’s employees (the “fear factor” Buffett wrote about in 2004). In the case of National Indemnity, when the business declined ~85% over 13 years, one can imagine that the number of people required to service the business was significantly lower by the end of that period. This brings us to the National Indemnity discussion at the 2004 shareholder meeting, which highlighted the crucial role that culture and incentives played at the insurer.

Here’s Buffett discussing the written premiums data shown above:

“I don’t think there’s another insurance company in the world that has a record like this. In the ‘hard market’ of the mid-1980’s, we got up to $366 million. And then we took it down - not intentionally, but just because the business became less attractive - all the way from $366 million down to $55 million. Now, the market became more attractive in the last few years, and it soared up to almost $600 million. I don’t think there’s a public company in America that would feel they could survive a record of volume going down like that, year after year after year after year. But that was the culture of National Indemnity… We don’t worry about premium volume.”

As suggested earlier, that’s a perfectly understandable conclusion from the perspective of the business owner. The big question is how you impart a similar way of thinking among the employees, who’s very jobs likely depend upon their ability to generate business (written premiums). Back to Buffett:

“If the silent message had gone out to employees that unless you write a lot of business you’re going to lose your job, they would have written a lot of business. National Indemnity can write $1 billion of business in any month if it wanted to, all it has to do is offer silly prices. If you offer a silly price, brokers will find you in the middle of the ocean at four in the morning. You cannot afford to do that. What we’ve always told people in our insurance businesses, and specifically at National Indemnity, is that if they write no business, their job is not in jeopardy. We cannot afford to have an unspoken message to employees that if you don’t write business, your job may be lost.”

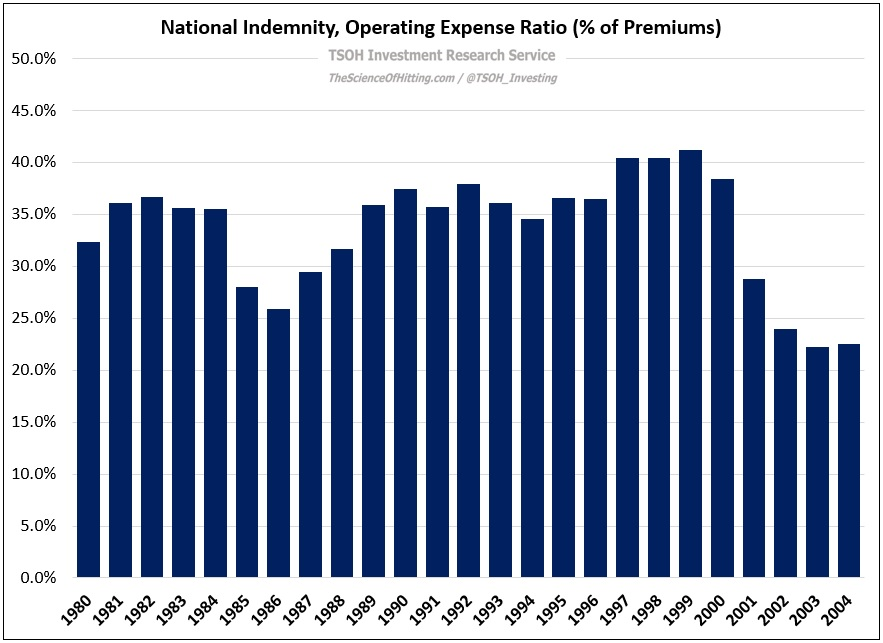

As Buffett went on to explain, National Indemnity never had layoffs during that difficult 13-year period (“other people would have, but we didn’t”); the number of employees naturally fluctuated as a result of attrition, but nobody was let go due to insufficient production. Unsurprisingly, that decision led to significantly reduced output per employee in the late 1990’s, along with a much higher expense ratio (up ~1,500 basis points from 1986 to 1999).

As Buffett keyed in on, there’s a critical trade-off / decision to be made by an insurer like National Indemnity: “Some companies would feel that having [a significantly higher expense ratio] would be intolerable - but what we feel is intolerable is writing bad business… If you get a culture of writing bad business, it’s almost impossible to get rid of. We would rather suffer too much overhead than to teach our employees that, in order to retain their jobs, they needed to write any damn thing that came along, because that’s a very hard habit to get rid of once you’re hooked on it… I think we’re almost the only insurance company in the world - certainly public - that sends the absolutely unequivocal message to the people associated with us that they will never be laid off because of a lack of volume.”

Where this story gets really interesting is when we look at the bottom line. The following two charts show the underwriting profitability of National Indemnity during the 25-year period from 1980 - 2004; the first is measured as a percentage of written premiums and the second is in dollars.

As you can see in the first chart, National Indemnity was consistently writing profitable business during this 25-year period (even during the 1990’s when it struggled to maintain its prior year volumes, let alone grow them). Despite the headwind on written premiums, the insurer kept its head above water by focusing on writing good business above all else (“even with a high expense ratio, you’ll see that we made money underwriting in virtually every year”).

The two charts in combination reveals a crucial feature of National Indemnity’s financials: the five best years during this period, measured by the underwriting percentage, were 1986 (~31% underwriting margin), 1987 (~27%), 1988 (~25%), 2003 (~18%), and 2002 (~17%). The combined written premiums during those five years was ~$1.94 billion, or ~$388 million per year – roughly 150% higher than the average throughout the whole 25 years. Said differently, when National Indemnity wrote its most profitable business (during “hard” markets), it was also writing a lot of business.

When you look at the 25-year period, the simple average underwriting margin is 6.6% per year. But on the cumulative results - $444 million in underwriting profits on $3.84 billion in written premiums – the underwriting margin is actually 11.6% - or 500 basis points higher than the simple average.

This shows why Buffett argued that what was truly intolerable for National Indemnity was underpriced risks, not temporarily outsized employee costs.

With the ability and willingness to patiently wait for those opportunities to aggressively underwrite new business, Buffett believed it could generate attractive results over time; as this data clearly shows, his assumption was correct. (“We coined money when we wrote huge amounts of business, and we made a little money when we wrote small amounts of business.”)

Conclusion

In response to Buffett’s long explanation of National Indemnity’s impressive results over the past 25 years, Munger tacked on his usual pithy reply:

“The main thing is that practically nobody else does it - and yet to me it’s obvious it’s the way to go. There’s a lot in Berkshire like that. It’s just a little different from the way other people do it; it’s partly the luxury of having a controlling shareholder of strong opinions… It would be hard for a committee, including a lot of employees, to come up with these decisions.”

In the case of National Indemnity, Berkshire appreciated the overwhelming importance of incentives. There was a disconnect between the short-term interests of the employee and the employer, and National Indemnity directly addressed that through its words and its actions / policies. Of paramount importance, they didn’t waver when times got tough (and for long periods of time). This may be “just a little different” – but it mattered hugely over time.

Among public companies, I’d argue that a willingness to accept significant and sustained short-term pain as a necessary cost of long-term prosperity is the exception, not the rule (as Tom Russo calls it, “the capacity to suffer”). At Berkshire Hathaway, the culture and incentives at the subsidiary companies are deliberately structured to encourage such an approach / perspective (it helps that Berkshire Hathaway, by nature of its diversification, isn’t beholden to the near term prospects in any given business or industry). In the short-term, the value of that advantage is difficult to quantity / pinpoint (imagine running a similar exercise to this one in 1999 instead of 2004); but as National Indemnity’s 25-year track record clearly shows, it shines clearly in the fullness of time. As a long-term investor, this is exactly what I’m searching for – and when found, it should be treated accordingly (held dearly).

Here's Buffett with the final word (and is it relates to the charts shown afterwards, note that this growth began with the $17 million of float brought on by National Indemnity in 1967; by 2004, the float attributable to National Indemnity was nearly $1 billion, with Berkshire’s total float at $46 billion):

“National Indemnity was a no-name company 30 years ago operating through a general agency system which everybody said was obsolete. It had no patents, real estate, copyrights, nothing that distinguished it, essentially, from dozens of other insurance companies... But they have had a record almost like no one else’s because they had discipline; they really knew what they were about. And they’ve stayed with that - in fact, they’ve intensified it over time. And their record has left other people in the dust. If you went to Wall Street with that record alone in 1990 or 1995, they’d say, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ The answer is nothing’s wrong with it. You put your finger on having the right incentives… You can’t run an auto company without layoffs; you can’t run a steel company this way. But this is the right way to run an insurance company. And that’s why cookie-cutter approaches to employment practices, bonuses, all that, are nonsense. You have to think through the situation that faces you in a given industry with its given competitive conditions and its own economic characteristics.”

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.