Lionsgate: An Attractive Minnow?

Is Lionsgate a target for the media industry sharks?

I opened the “WarnerMedia + Discovery” post with the following:

“On Monday, May 17th, AT&T’s WarnerMedia and Discovery announced their intentions to combine - and in doing so, they dropped the first domino in the next wave of media industry consolidation.”

Since that deal was announced, I’ve been thinking about the implications of that first domino. My sense is that the deal announcement will inevitably lead to soul searching at companies like NBCUniversal and ViacomCBS – and with that soul searching, additional dominos may fall.

A second deal has already been announced: on May 26th, Amazon reached an agreement to acquire MGM Studios for $8.5 billion (inclusive of debt). As noted in the Wall Street Journal, the companies had been in on-and-off discussions for about 18 months; those conversations became serious “about five weeks ago”, in mid-to-late April, when Amazon upped its offer to more than $8 billion.

Given the timing, I do not think that Amazon’s decision to raise its offer for MGM Studios had anything to do with the WarnerMedia / Discovery deal. Instead, it may have been a reaction to the announcement in early April that Netflix had secured a five-year agreement with Sony Pictures Entertainment for the exclusive U.S. rights to the studios’ films beginning in 2022. The company that will be losing the Sony rights, Lionsgate, is the focus of today’s article.

As the sharks in the media industry look to strengthen their DTC offerings, the remaining minnows (companies like MGM Studios) are likely targets. Lionsgate, which has a market cap of roughly $4.3 billion, fits that bill. (This isn’t a new idea: Lionsgate has been discussed as an acquisition target for years.)

So, what is Lionsgate? At a high level, it’s a collection of film and television studios; its labels in the United States include Lionsgate, Summit Entertainment, Good Universe and Roadside Attractions (acquired 43% in 2007). In addition, following the $4.4 billion acquisition of Starz in 2016, the company now owns a premium video platform offered in more than 50 countries globally. Finally, Lionsgate has accumulated a content library with roughly 17,000 films and TV episodes, “one of the largest collections… in the independent media space”.

An important point as it relates to Lionsgate is how they finance and monetize their studio output. As noted in the 10-K, the company “mitigates financial risk” by co-financing and co-producing content, pre-licensing international distribution, offering higher talent participation on the back end in exchange for lower upfront payments, etc. As shown below, while those decisions can meaningfully reduce the company’s at-risk capital, the trade-off is it limits their upside on a hit show or movie, as well as the long-term control of that content.

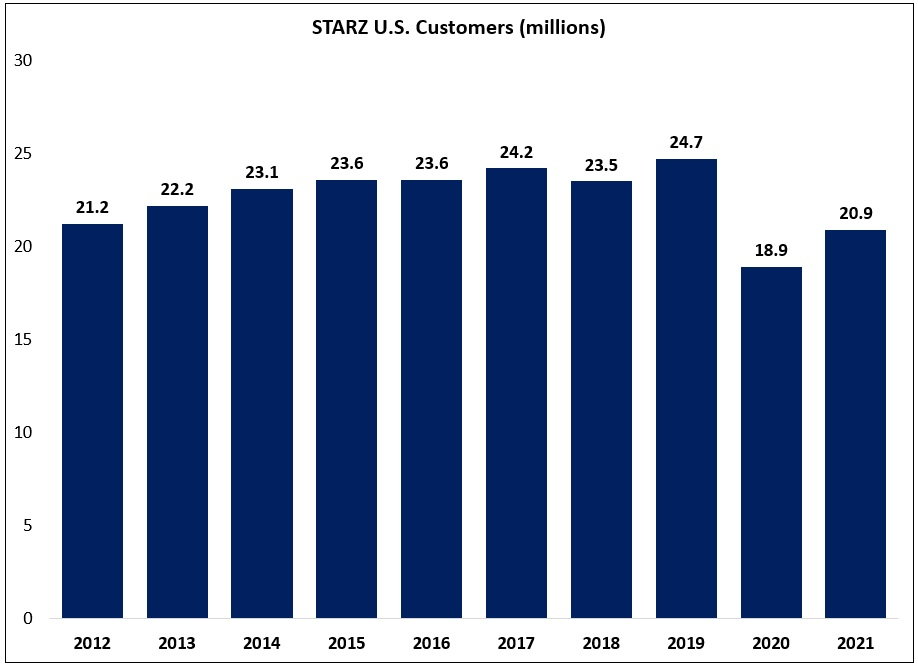

The Starz acquisition was an opportunity to change that. Lionsgate could have used its production capabilities to strengthen the original programming and library content offered across Starz (its TV channels and OTT offering). But it never happened, with Starz left to languish: as shown below, the total Starz U.S. subscriber base has flatlined over the past 5-10 years, a period where services like Netflix added tens of millions of U.S. subscribers (the large FY20 decline reflects the decision of some key distributors to drop Starz from its packages).

In addition to lackluster subscriber figures over the past decade, Starz has other problems around the corner: as mentioned earlier, Netflix has secured the U.S. rights to the theatrical slate from Sony Pictures Entertainment beginning in 2022 (includes all titles released under the Columbia, Screen Gems, Sony Pictures Classics and TriStar labels). That agreement came at the expense of Starz, which has had a studio output agreement with Sony for about 20 years.

And it gets worse: as shown below, Starz has “significant library programming agreements” with Paramount and Warner Bros that expire over the next 18 months. When that happens, I assume both companies will take back that content for their DTC services (Paramount+ and HBO Max, respectively). The same goes for the Miramax agreement expiring in early 2023 (ViacomCBS owns 49% of Miramax). As time goes by, the content currently being supplied by the major media companies to Starz is likely to leave - and even if they eventually return to a licensing strategy (as a result of failed DTC efforts), Starz will be unable to match the firepower of bidders like Netflix given its lack of scale.

There’s an interesting – and, in my mind, revealing – side note to add here: the chart shown above was pulled from the FY20 annual report. The reason why is because in the updated version of that chart from the FY21 annual report, management chose to no longer disclose the end date of these agreements:

In my book, that’s a pretty serious red flag. I think LGF management has purposefully obscured the details of its “significant” library agreements. The reason why is self-evident: they realize Starz will be in an increasingly difficult position as it loses much of its programming over the next few years.

A Familiar Face

As is often the case in the media industry, Dr. John Malone has ties to this story. In February 2015, when Malone was a major Starz shareholder, he negotiated a stock swap agreement with Lionsgate (following the transaction, he still owned more than 6% of Starz). A year later, as a result of the Starz acquisition, Malone became a major shareholder of Lionsgate. When that deal closed in December 2016, LGF.A traded around $26 per share.

Fast forward to November 2019: in an interview with CNBC’s David Faber, Malone was asked why he had decided to sell Lionsgate. This was his response:

“I sold because I didn’t see them execute a strategy of using their library and content capabilities to drive Starz. I really thought the opportunity was to use Lionsgate’s creative skills to drive Starz globally, aggressively. And, in my opinion, they got hung up on selling our content to somebody else versus putting it on our own distribution. My concept originally when I went into it was that they were going to drive their own distribution. I also thought that if they were successful with that, they would make themselves much more valuable to other people. They didn’t do that, and I became discouraged with their ability to do that… It’s the question you started with: who’s going to win in the streaming game? And I didn’t see a path for that company to be a winner… This is a scale game, and you’ve got to be global to get scale in scripted. Or you’ve got to drive yourself towards narrow niches where you have uniqueness because the big guys don’t care about that niche. You’ve got to go one way or the other.”

I think that conclusion is spot on.

Lionsgate will continue to serve a need as a supplier to linear channels and OTT services; whether that will be a good business is a different question (Malone: “The margins in that are pretty thin… I don’t think that’s a good place to be… at that point you’re manufacturing widgets… that’s a shitty model”). Starz, on the other hand, appears to be in a tough spot: they are sub-scale and will lose much of their content over the next few years as studios like Paramount and Warner Bros regain control of their library. To Malone’s question, “who’s going to win the streaming game?” I’m pretty confident “Starz” will not be the answer.

But even if Lionsgate does not have a bright future as a standalone company, would it be an attractive target for NBCUniversal or ViacomCBS?

I don’t think so.

The problem is that’s Lionsgate’s business model – “selling content to somebody else” – is incongruent with the needs of its DTC business. Look no further than the July 2020 decision to license the popular TV series Mad Men as opposed to retaining the rights for Starz. In addition, given the massive ramp in content investments by media companies over the past decade, I’m of the belief that most library programming will see its value decay more quickly than in the past (with so much “new” content being put out every month by Netflix, Disney+, HBO Max, etc., I think that the number of older shows that will manage to maintain a place in the cultural zeitgeist, like The Office and Friends have, will be limited).

Conclusion

From the perspective of a media company looking to add additional firepower to its DTC business, what’s the real value of the 17,000 titles in Lionsgate’s library? The answer is that the most valuable content / IP that Lionsgate owns is already being monetized via licenses (again, consider what they did with Mad Men). For a potential acquirer, that means Lionsgate would do very little to help strengthen their DTC offering(s), at least in the short-term. If the idea was to buy Lionsgate to utilize its library, an acquirer would need to (1) wait years for current agreements to expire; and (2) completely disrupt the company’s business model.

In numbers, Lionsgate generated $3.3 billion in revenues in FY21, with about half from Media Networks (Starz Networks U.S. and STARZPLAY International). If you pursued the strategy outlined above, a large percentage of Lionsgate’s remaining revenues would go to zero (in FY21, Lionsgate’s film and television library revenues were $780 million). The point is that executing this strategy would put a big hole in Lionsgate’s income statement - and that’s before considering the $8 billion or so you’d likely have to pay to acquire it (including net debt).

Long story short, I do not believe that acquiring Lionsgate would be the highest and best use of capital by NBCUniversal or ViacomCBS. As a corollary, assuming none of the sharks are interested in this minnow, there are real concerns about what this business looks like in five years (especially Starz, which accounted for roughly half of the company’s adjusted OIBDA over the past two years).

For that reason, I’m not interested in Lionsgate.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial, accounting, tax, or other adviser or in any fiduciary capacity.

I agree with you thesis. I was an LGF holder a couple of years ago and suffered a small loss. I revisited it several times and did not see anything compelling. When Malone bails that speaks volumes. Thank you for the analysis.