Returns and Lessons Learned

Some lessons learned from past investment experiences

J.C. Penney, IBM, and Kraft Heinz.

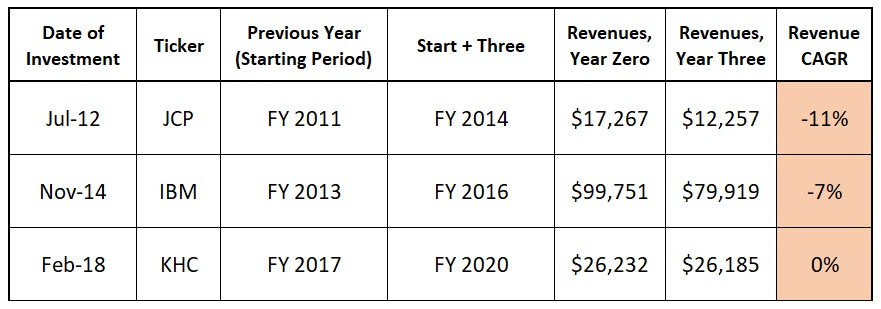

Over the past decade, these were my most notable investment failures. While each situation had its own unique circumstances, the underlying problem proved similar. Consider the following data, which shows the three-year revenue CAGR (compounded annual growth rate) for each company following my investment.

In the three-year period, each company failed to report growth – and for IBM and JCPenney, revenues declined meaningfully. While some company specific developments played a role, such as asset sales at IBM, the inability to grow points to a larger issue: at the time of my investment, each company had already lost some of its standing in the eyes of customers relative to the competition.

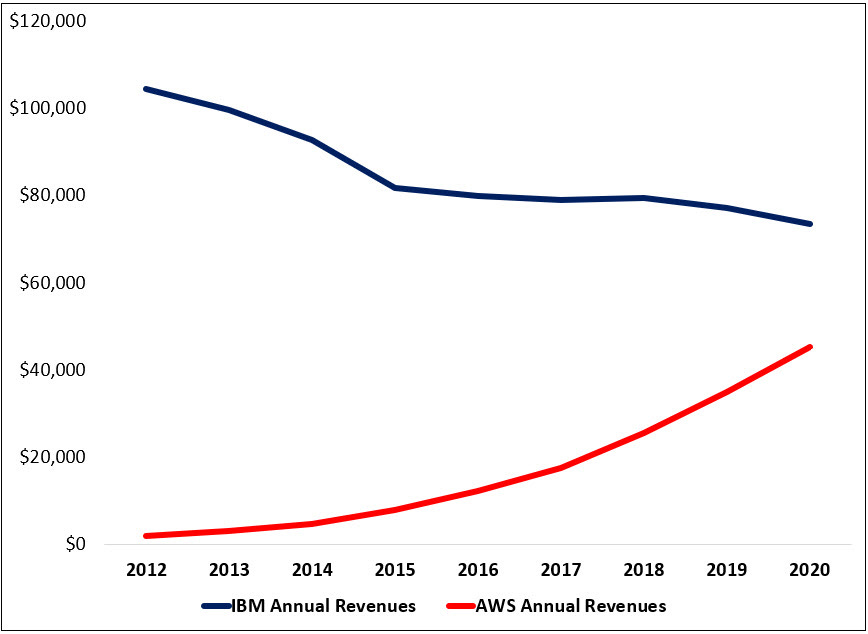

For JCP, the primary culprit was the demise of traditional shopping malls, led by companies like Walmart, Target, TJX, and (more recently) Amazon. For KHC, it was a combination of private label competition (like Costco’s Kirkland brand) and emerging brands like Sir Kensington’s and Annie’s (and in that case, I also overpaid due to erroneous expectations related to future M&A opportunities). At IBM, while revenues declined year after year, competitors like Amazon (AWS) and Microsoft (Azure) built cloud businesses that are now generating tens of billions of dollars in annual revenues. (AWS, which generated <$2 billion in sales in 2012, will likely be larger than IBM’s entire business within five years.)

In each situation, the company faced significant competitive pressures prior to my involvement. Given that reality, why did I still make the investment? The answer is I managed to convinced myself that the price offered by Mr. Market was still attractive, even after accounting for these concerns. I was wrong.

Here’s my first takeaway from these investments: if a company is losing relevance with customers, that’s a major red flag. As a corollary to that idea, if a company is unable to generate organic revenue growth, outsized returns for shareholders is an unlikely outcome over the course of the next 5-10 years.

I realize those conclusions are blindingly obvious. Why would I commit capital to the incumbents who were facing disruption as opposed to the innovators that were taking customers and market share? The answer is that, all else equal, I’d naturally avoid the former for the latter. The problem was (and still is) that the companies in these buckets are far from equal on one key variable: valuation.

Ultimately, I let these valuation concerns become a justification for investing in the companies that faced a difficult hand, a reality that was clearly evident prior to my involvement (but one that I wrongly believed was being overstated).

In the choice between a good business at a fair price and a (seemingly) fair business at a (seemingly) good price, I mistakenly chose the latter.

The takeaway, in my mind, is a slight tweak of my earlier conclusion: while a reasonable valuation is important to long-term investment success, it should be of secondary consideration in the research process. The first filter must be business quality. Unless it’s a high-quality business, it doesn’t matter if the stock trades at a discount to book value or a double digit FCF yield - for me, it’s a pass.

This isn’t a knock on value investing or “cigar butt” investing generally. There are people who successfully operate with that strategy – but I’m not one of them (or at least I haven’t been in the past). Simply put, it’s not the game I desire to play.

I’d encourage subscribers to keep me honest. In the future, if I comment favorably on an idea and you have questions about the quality of the business, let me know.

Now that we’ve discussed the pain of past failures, let’s turn to a happier subject: winners. I’ll look at a few notable examples from the past decade that I believe highlight the type of situations I can effectively navigate as a long-term investor.

The first is Microsoft, an investment which dates to February 2011 (it has been a large holding ever since). In the two years following my initial investment, the stock went nowhere, compared to an increase of ~15% for the S&P 500. It was my actions when the investment started to work, particularly after Satya Nadella became CEO in 2014, where I “earned” my returns (as I wrote at the time, the consensus view of Mr. Nadella as an insider - meant as a pejorative - was misguided). The story and business evolved, and I did a good job updating my expectations along the way. Continued learning is what enabled me to hold a large and growing position as the stock reached new heights, and to participate in the gains reaped over the past decade: since February 2011, the stock has delivered a total shareholder return (TSR) of more than 1,000% (~27% annualized).

The second is The Walt Disney Company, which was preceded by an investment in 21st Century Fox (when Disney acquired the majority of 21CF’s assets in March 2019, I elected to receive DIS shares). Much like Microsoft, what’s instructive about this investment is how my thinking has evolved over time, which led to conviction in the thesis and positioned me for long-term success. In numerous articles and podcast appearances over the past two years, I have highlighted the importance of Disney’s best-in-class IP / brands, as well as their unrivaled ability to effectively monetize those assets across their collection of businesses (theme parks, movie theaters, consumer products, etc.). An appreciation for Disney’s sustainable competitive advantages, as well as the incremental long-term opportunities that would be created in a direct-to-consumer (DTC) world, helped me to weather the early months of 2020, when concerns about theme park and movie theater closings pushed the stock to levels last seen in 2014. A year later, Disney shares trade at $189 per share, up more than 100% from March 2020 lows.

The final example is Facebook, which I largely bought in October 2018 as a swap for PepsiCo (FB shares are up ~105% since the change, compared to a ~30% gain for PEP). I wanted to call out this transaction because it speaks to how I think about risk and reward. One of Warren Buffett’s most popular investing quips is “Rule #1: Don’t lose money. Rule #2: Never forget rule #1.” As a big fan of Warren, I want to be clear: I do not follow that rule (at least not at the level of an individual investment within the context of a portfolio). If I did, I would not have swapped FB for PEP because I think the former has higher terminal value / duration risk than the latter. The reason why I still made that change is because I believed the potential upside from an investment in FB over the long run provided sufficient compensation relative to the risk incurred. As a subscriber, it’s important for you to have an appreciation for how I view the opportunity set and where I’m willing to accept incremental risk in exchange for incremental (expected) return.

Conclusion

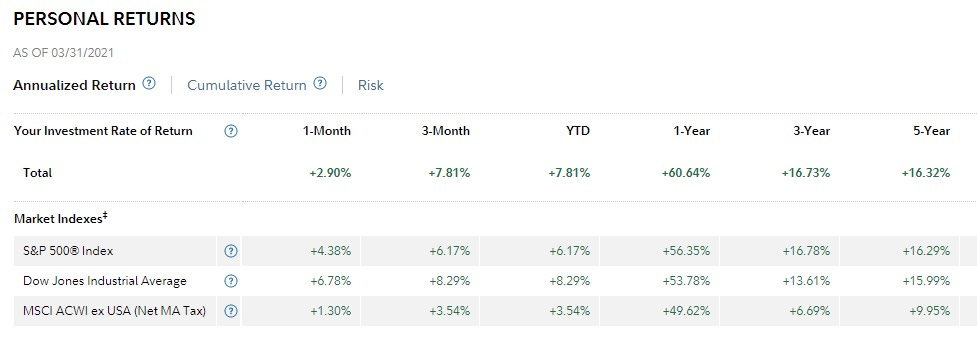

This data, calculated by Fidelity, shows my portfolio returns through the end of March 2021. It includes all investable assets that I have outside of my 401(k).

My returns over the past three-year and five-year periods have been comparable to the S&P 500 (to be clear, this is a calculation of overall portfolio returns; to the extent I’ve held cash or fixed income securities, it is reflected in these results). Frankly, given how I approach security selection and portfolio construction, I find it surprising I’ve managed to keep pace with the S&P 500 in recent years.

My expectation is that continued growth as an investor, particularly as a result of the painful (and expensive) lessons learned from previous mistakes, will help me to further improve upon this performance in the years ahead.

In my next post, “April 2021 Portfolio Review”, I’ll take an in-depth look at each company that I’m currently invested in, including my thoughts on valuation.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial, accounting, tax, or other adviser or in any fiduciary capacity.

KHC had 3G and Buffett's involvement 3 years prior to your investment. JCP had Ackman's involvement 2 years prior. Did their involvement influence your decision to buy at all? If so, are there any lessons for how much weight to put on activists' involvement today, for example Elliott in MTCH?

Nice work.

is your portfolio from a standing start or did you add funds to the account between the 2011 first purchase of MSFT and then subsequent stock buys? Like do you need to sell something to buy something new or do you add funds, because that's obviously a different benchmark to SPY which would be static.