On Consistency and Simplicity

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

Charlie Munger, 1989 Wesco Financial Annual Letter (page 87)

In August 1981, Dean Williams of Batterymarch Financial Management gave a speech at a financial analysts conference titled “Trying Too Hard”. Among many useful ideas presented by Williams, I was particularly drawn to this one: “The last of the mental qualities we talked about was consistency... and how it seemed present in nearly all outstanding investment records... Simplicity or singleness of approach is a greatly underestimated factor of success.”

Simplicity can be an uncomfortable idea in the world of investing, particularly as it relates to the business of investing. One notable way that it surfaces is security / fund selection, an example of which I saw recently when a family member asked me for some thoughts on an account that was being managed by a large investment advisory firm. The portfolio consisted of a complex web of about 25 different funds, many of which had portfolio weightings of <3%.

Its construction signaled great thought and effort - yet the portfolio, over the long run, was highly unlikely to generate returns that diverged from those delivered by a sensibly constructed portfolio with three or four index funds (before considering the elevated expense ratios on many of the ~25 funds). To paraphrase Morgan Housel, it’s likely the best answer for my family member would’ve been if the individual managing the portfolio did next to nothing - but their career incentives encouraged them to do something.

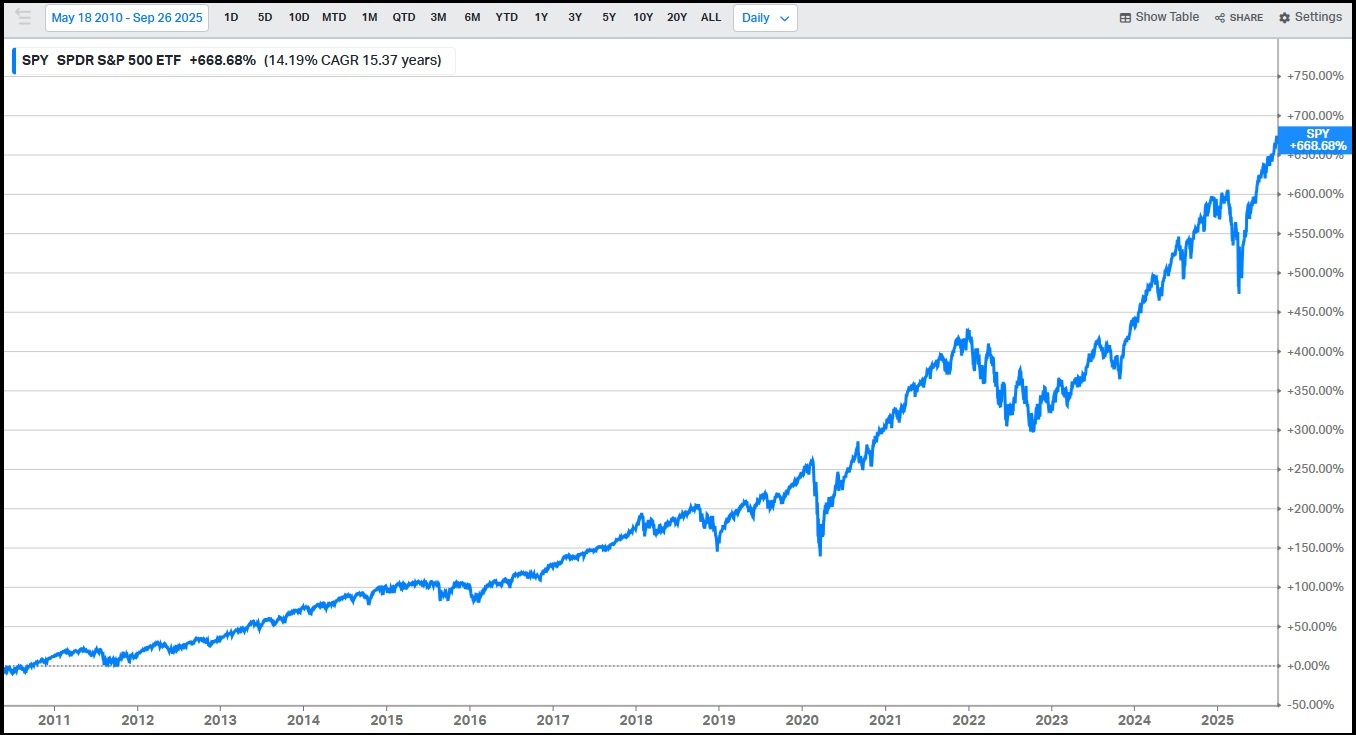

Beyond security and fund selection, asset allocation is another area where simplicity is often meet with suspicion; a structural approach, with weightings largely fixed outside of periodic rebalancing, lacks the apparent sophistication of big swings in / out of equities (i.e. market timing). The past 15+ years have revealed the danger that lurks here; a particularly notable example is from Seth Klarman, who said the following at the CFA Institute Conference in May 2010: “I am worried about the world, more broadly, than I’ve ever been in my career... Given the recent run-up, I am worried we will have another ten years of, if not zero, at least very low returns from today’s valuations.”

In hindsight, the S&P 500 bested Klarman’s prediction by a massive margin - more than ten percentage points per year. Those who stuck to simplicity, an acceptance that the continued ownership of U.S. businesses was likely, at a minimum, to be the least bad option, have been handsomely rewarded. (On Klarman, it’s worthwhile to consider the following quote: “We started with a risk aversion, and I was probably a good match for that... People think that they’re hiring a manager to make them money, but they’re probably hiring a manager to keep them out of trouble, and maybe to fight their own instincts.” He has his own incentives / risk tolerances to consider in running Baupost.)

That surely isn’t to say it has been easy to stay invested along the way, particularly as Mr. Market has responded to growing concerns about equity levels with higher prices and higher valuations: the S&P 500’s P/E multiple and EV/EBITDA multiple was up to the 99th percentile in 2015 - and then, over the next ten years, the index more than tripled from ~2,100 to ~6,600.

Which brings us to a critical question: What’s a sensible way for a long-term investor to navigate a market like the one we’re witnessing? How can we steer clear of the missteps that may prove extremely costly over time?