GEICO: The Gecko Stumbles

At the 1996 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were asked about GEICO (at the time, the seventh largest U.S. auto insurer). While Berkshire owned ~50% of GEICO by the mid-1990’s (for which they’d paid $45.7 million, with a lot of help from share repurchases over the years), a January 1996 deal gave them control of the other 49% - at a cost of $2.3 billion. As Buffett wrote in 1995, “That is a steep price.”

The question at the 1996 meeting related to that “steep price”: what led Buffett and Munger to pursue the GEICO deal, and how would the auto insurer impact the growth / value of Berkshire’s broader insurance business over time? In response to that question, Buffett said the following:

“We paid a good price, but GEICO is a terrific company. It has outstanding management. It has a low-cost method of distribution, which is very difficult [to compete with]; everybody wants to have that, but very few come close. GEICO management is focused on bringing costs down further and widening that competitive moat. I personally think GEICO’s growth rate is likely to be greater in the future than where it’s been in the past… There are some advantages to being part of Berkshire; there are costs to bringing new business on the books, and we don’t care at all about quarterly earnings. GEICO was relatively insensitive to those concerns before… but they had more pressure on them in respect to reported earnings than they will have as part of Berkshire. And I think there’s some really big opportunities, in terms of what can be done as part of Berkshire. So, I think five years from now, you’ll be very happy that we own 100% of GEICO… As marvelous as GEICO was independently, it will flourish even more as part of Berkshire.”

As he so often does, Buffett captured what would be critically important for this business over the next 10-20 years in a few sentences. Specifically, there are two comments about GEICO that stand out to me: (1) it’s low-cost method of distribution; and (2) the removal of incentives that likely impacted management’s decision-making when GEICO was a publicly traded company.

On the first point, there are a few important characteristics about the auto insurance industry: (1) it’s a relatively expensive product (premiums per average policy were ~$1,250 per year in 1995); (2) it’s a mandatory purchase (you have to have auto insurance to own / drive a car); and (3) it’s an offering where customers do not generally assume a meaningful difference in product or service quality among the established competitors like State Farm, GEICO, Progressive, etc. (Tegus interview with a former Marketing Director at State Farm: “It moved from a value-driven category to a price-driven category”)

As Buffett discussed at the 2004 meeting, those conditions informed the strategy that would be most effective in this industry: “Saving significant money makes a real difference in a lot of household budgets, so low cost is going to win… It’s a better system, and better systems win over time… We have a very tough competitor in Progressive because they’ve seen how well our model works, and they, in effect, shifted over [from an agency model to a direct model]… It’s always a good idea to go with a low-cost producer over time. You can mess it up in other ways, but being a low-cost producer of something essential to people is usually going to be a very good business.”

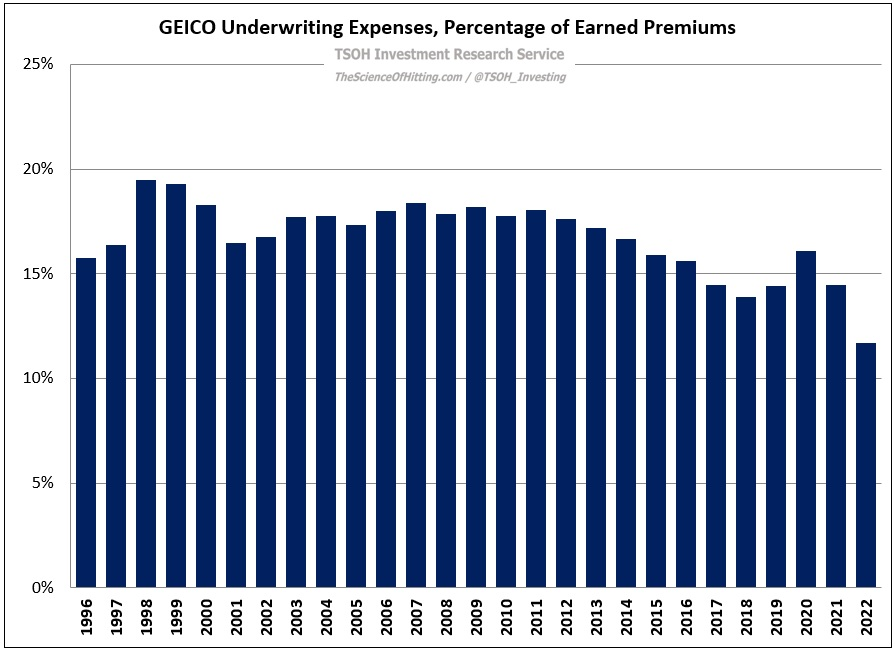

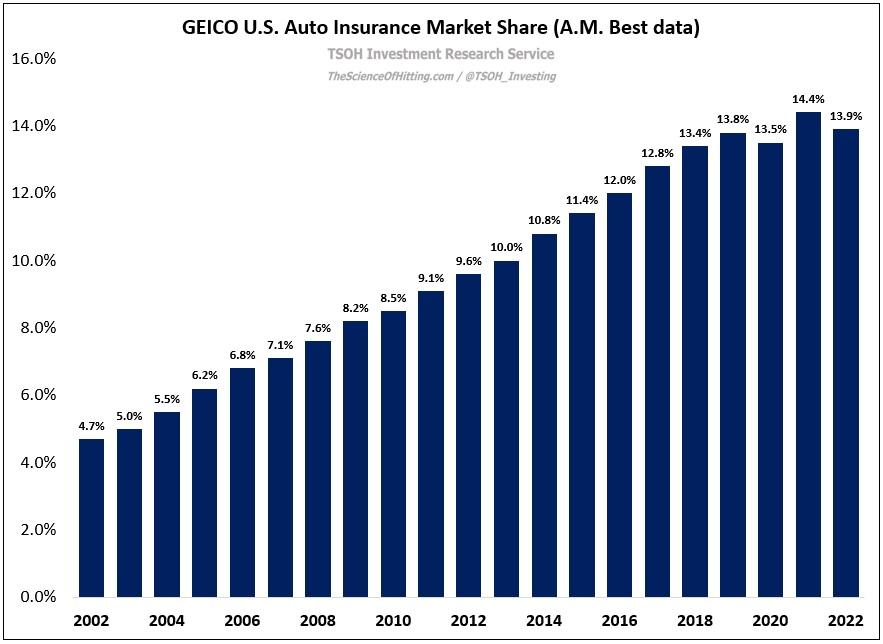

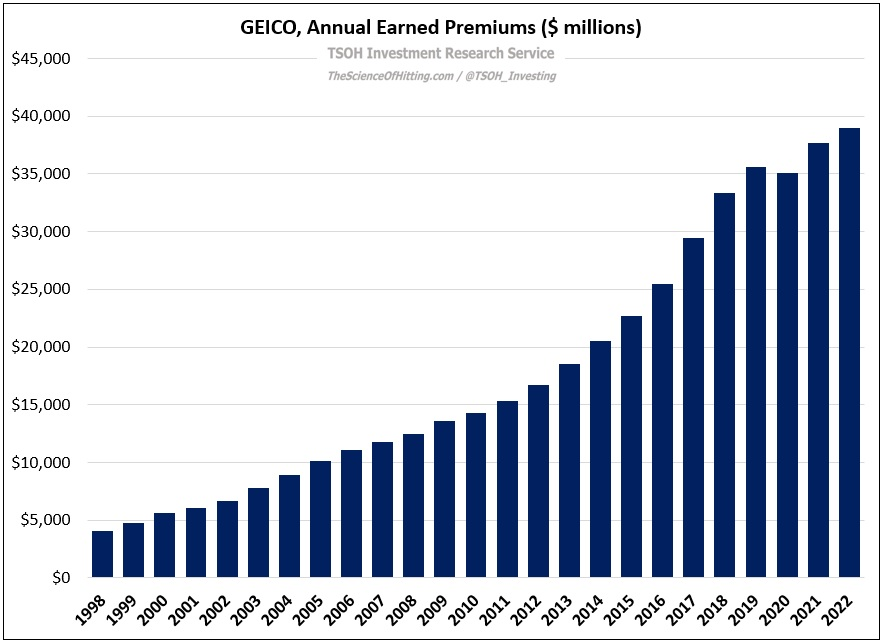

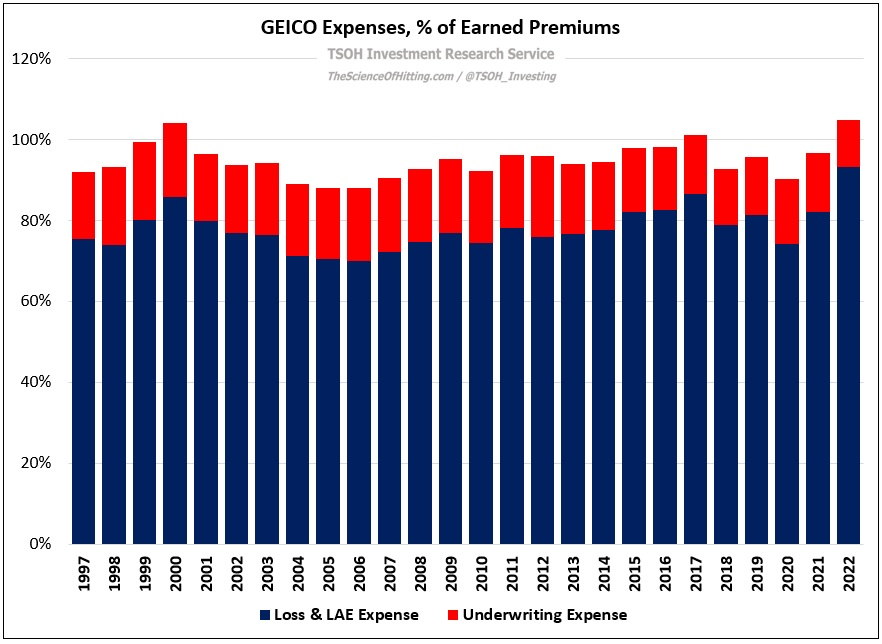

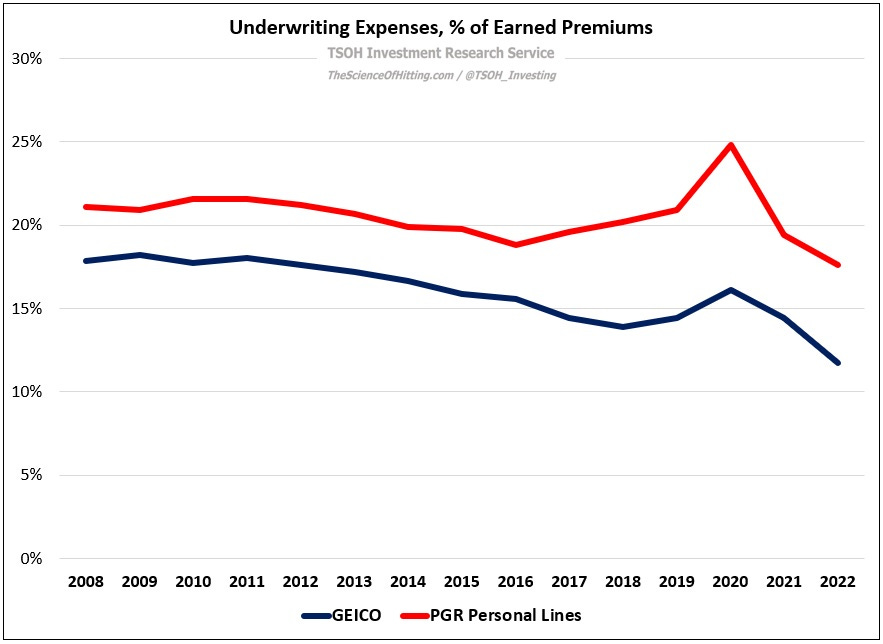

The following chart shows GEICO’s underwriting expenses as a percentage of earned premiums. As you can see, GEICO’s cost structure has significantly improved over the past 25 years (that wasn’t the case in the late 1990’s and the early 2000’s, which I’ll discuss in a moment). As Buffett noted at the 1996 meeting, sustaining and improving GEICO’s low-cost position was key to widening its moat. Given that GEICO’s customer base (voluntary auto policies in force, or PIF’s) has grown by >7x from 1995 to 2022, it’s clear that this has been a successful strategy that resonated with consumers.

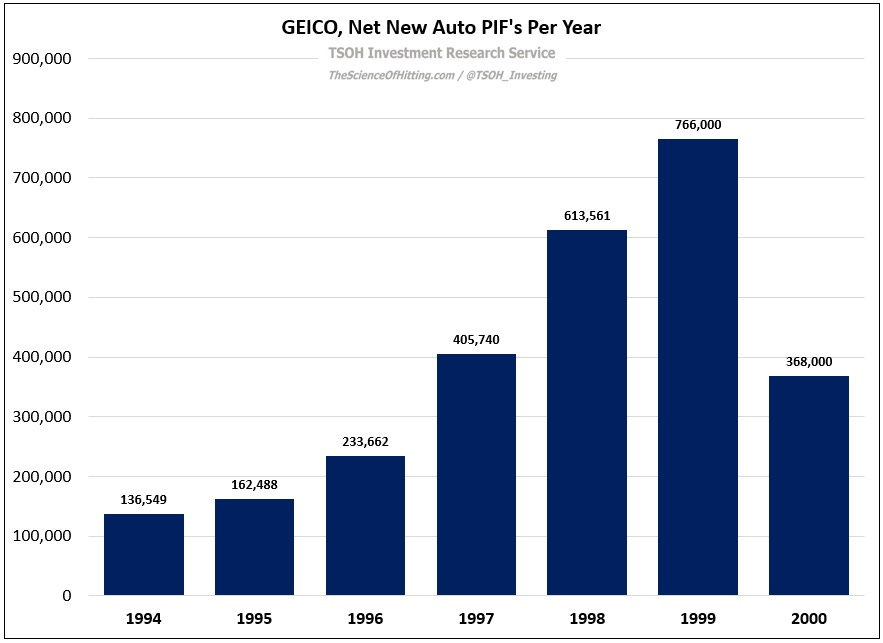

This brings us to the second noteworthy point from Buffett’s 1996 comments (“there are costs attached to bringing new business on the books, and we care not at all about reported quarterly earnings”). Growing the business came with two headwinds for GEICO: first, they have to spend on marketing to attract new customers (expensed immediately through the P&L); second, once they add a new policyholder, it takes some time before reaching the level of profitability that is expected for seasoned customers (as Buffett mentioned at the 2017 shareholder meeting, loss ratios in year one for a new policyholder are nearly ten points higher than on renewals). When GEICO was a public company, even if they knew the next cohort of customers would deliver attractive long-term economics, this was a constraint given its short-term impact on earnings (EPS). As a subsidiary of Berkshire, GEICO was no longer constrained by this short-term financial consideration.

This impacted the business in two ways: First, it led to a significant increase in marketing spend, which explains the heightened underwriting expense ratios during the late 1990’s mentioned earlier; as Buffett disclosed in the 1999 letter, marketing spend was $242 million that year – nearly 7x higher than the $33 million GEICO allocated to marketing in 1995. Second, and more importantly for the long-term economics, this spend led to a significant acceleration in customer (PIF) growth rates: as shown below, after adding ~150,000 net new customers on average in 1994 and 1995 (before the deal), GEICO added nearly 500,000 net new auto PIF’s annually, on average, throughout the end of the decade (the five-year period from 1996 to 2000).

As you look at the above chart, you’ll notice that the results in 2000 were much weaker than in the years preceding it. As Buffett discussed in that year’s shareholder letter, this reflected a number of issues, including less effective marketing spend (which drove higher policy acquisition costs), ongoing societal considerations (older generations were more reluctant to deal with direct insurers), and some noteworthy decisions by competitors (specifically State Farm, which was “very slow” to adjust its auto pricing in the face of rising loss rates). What’s most interesting about the 2000 letter isn’t Buffett’s explanation of GEICO’s current challenges (which he spoke about directly); instead, it was his thoughts on the structural considerations in the business / industry that would be the long-term wind in GEICO’s sails:

“GEICO will be a huge part of Berkshire’s future. Because of its rock-bottom operating costs, it offers a great many Americans the cheapest way to purchase a high-ticket product that they must buy. The company then couples this bargain with service that consistently ranks high in independent surveys. That’s a combination inevitably producing growth and profitability.”

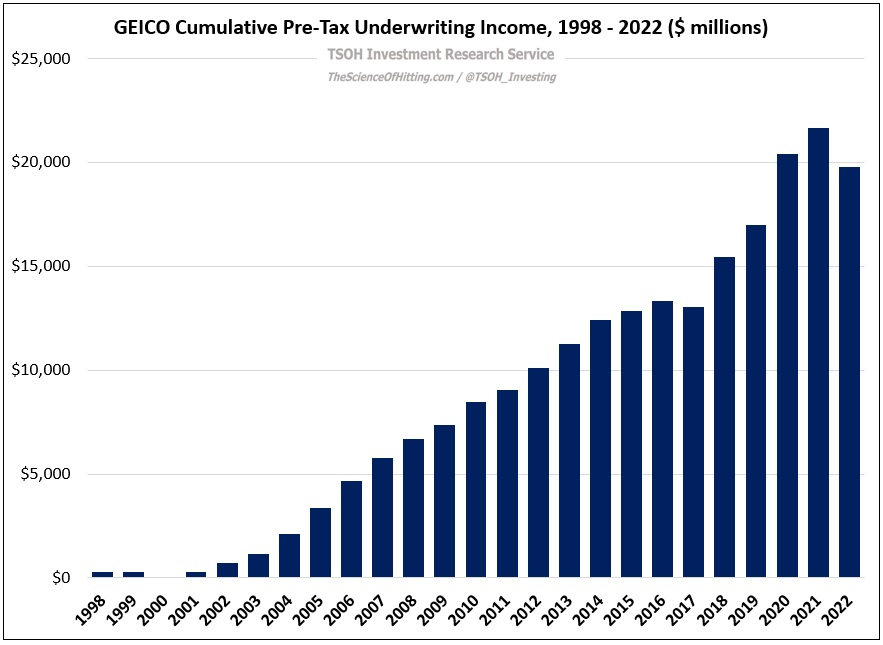

As we look to the long-term results, that shines through: in addition to significant earned premiums growth, GEICO has generated ~$20 billion of cumulative pre-tax underwriting income over the past 25 years.

The Progressive Problem

While that “inevitability” was on display for the better part of the next two decades, GEICO now finds itself playing catch-up to an aforementioned competitor: Progressive. To put it bluntly, Progressive has ran laps around GEICO over the past few years. As shown below, GEICO had 4.5 million more auto PIF’s than PGR at the end of 2017. That advantage has completely disappeared over the past five years: Progressive now has a larger auto insurance business than GEICO (measured on PIF’s).

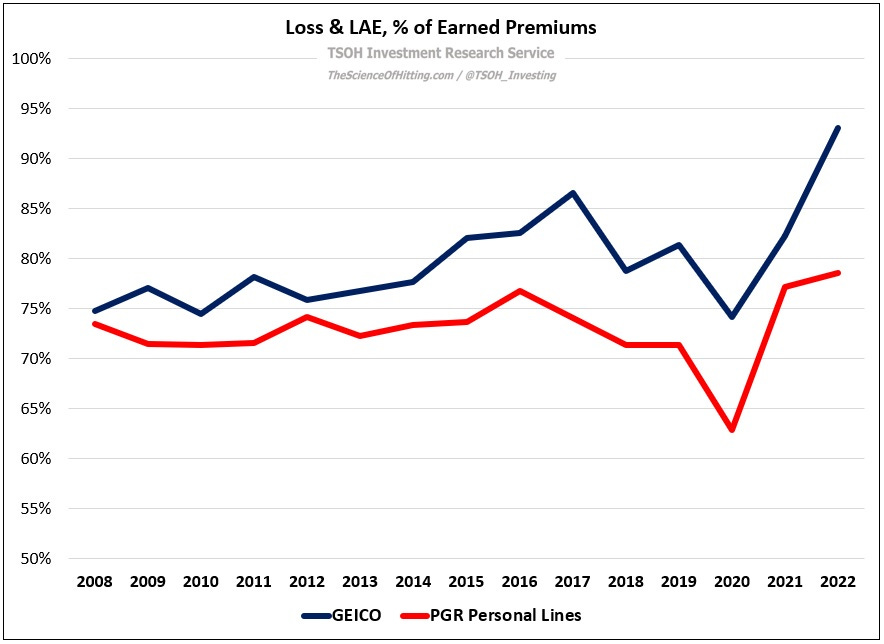

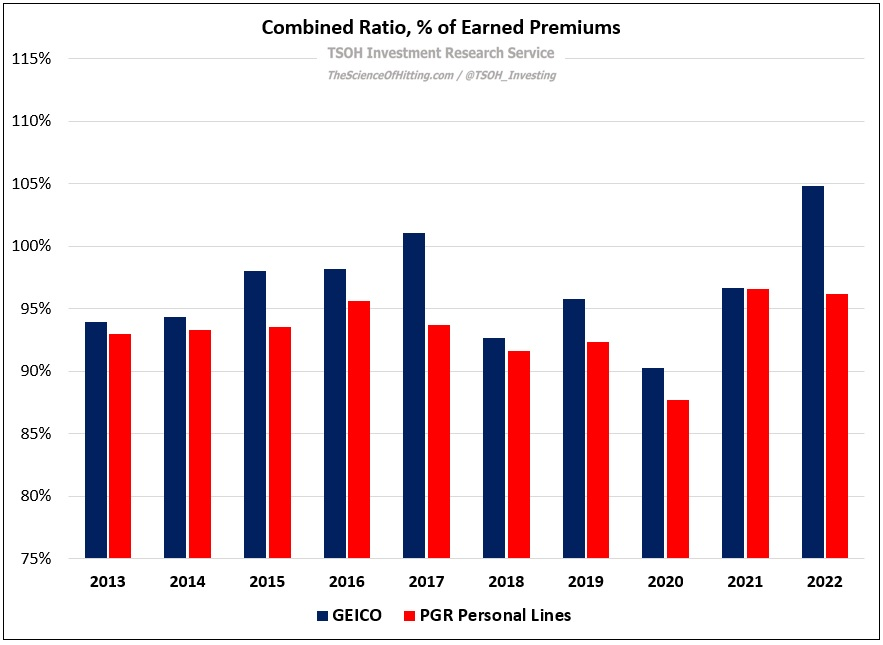

The problem doesn’t end there. While the pandemic has had a significant impact on the annual figures, the chart below shows that GEICO’s loss & LAE (the costs associated with covering insurance losses) has averaged ~82% of earned premiums over the past five years, inclusive of a ~93% loss & LAE rate in 2022. While GEICO has largely protected underwriting profitability by continually reducing underwriting expenses (as a percentage of premiums), it’s clear that they have work to do on the cost structure: In 2022, PGR’s Personal Lines business, with Auto accounting for >90% of written premiums in Personal Lines, reported a +4% underwriting margin - 900 basis points better than the -5% underwriting margin reported at GEICO. (2022 10-K: “We currently expect GEICO to generate an underwriting profit in 2023.”)

Simply put, GEICO has been handily beaten by Progressive over the past handful of years on volumes and underwriting / profitability. This reality hasn’t been lost on shareholders or Berkshire management (it has been a frequent topic of discussion at the annual meetings). This comment, from Buffett at the 2012 meeting, is noteworthy; in hindsight, I bet he’d agree that he overstated GEICO’s competitive position, at least relative to Progressive:

“Progressive has probably been the leader in what you described [telematics]. We have not done that at GEICO, but if we think there becomes a superior way of evaluating the likelihood of anybody having an accident [we’ll do it]… Obviously, if you could ride in a car with somebody for six months, you might learn a bit about the propensity [of having an accident], particularly if they didn’t know you were there… But I do not see that as being a major change … We’re always looking for more things that will tell us someone’s likelihood of having an accident in the next year… but I don’t think that this new experiment threatens GEICO… Our marketing, risk selection, and retention are working extremely well. GEICO is a machine.”

Buffett took it a step further at the 2013 meeting:

“I don’t think - but obviously Progressive disagrees - that their selection method is better than ours. And I would say that I might even feel ours is a little bit better than theirs… I invite you to compare the Progressive results with GEICO’s over the next two or three years, and if we’re wrong, I will freely admit we were wrong - but I don’t think we will be.”

(A few weeks later, in May 2013, former Progressive CEO Glenn Renwick said the following at an investor event: “From what I know, I don't believe GEICO is interested in usage-based insurance. We believe it’s an incredible segmenter for new business in the marketplace.”)

It took longer than Buffett’s 2-3 year time horizon, but that day ultimately came; Progressive has outpaced GEICO by a wide margin over the past five years. The GEICO machine isn’t running as smoothly as it once was. As that became apparent, the discussions (rightfully) changed. This comment, from Ajit Jain at the 2019 meeting, quantified the problem:

“GEICO has a significant advantage over Progressive on the expense ratio, about seven points or so. On the loss ratio side, Progressive does a much better job; they have about a 12 point advantage. So, net-net, Progressive is ahead by about five points [on the combined ratio]. GEICO is very aware of this disadvantage on the loss ratio that they’re suffering, and they’re very focused on bridging that gap as quickly as they can… I’m hopeful we’ll catch up on the loss ratio and maintain the expense ratio advantage.”

The following charts compare GEICO and Progressive over the past 15 years on both of those variables; as you can see, while GEICO has sustained its large expense ratio advantage over Progressive, it is underperforming – and by a significant margin - on loss & LAE (as well as on volumes / PIF’s).

At the 2021 meeting, Buffett bluntly stated what the numbers showed: “Progressive has had the best operation in recent years in terms of matching rate to risk – and that’s what insurance is all about.”

Jain followed on, admitting that GEICO was mistaken to dismiss the role of telematics / usage-based insurance (UBI) in the auto insurance business: “GEICO missed the bus and were late in terms of appreciating the value of telematics; they’ve woken up to the fact that telematics plays a big role in matching rate to risk… I think GEICO is catching up with Progressive.”

In response to those comments, Progressive CEO Tricia Griffith said the following: “GEICO is a formidable competitor… We've had an edge on a lot of our competitors for many years now - and we're not going to stop… Segmentation is a key facet of our competitive prices, and nowhere is that more evident than our investment in UBI… UBI is our most predictive rating variable and it provides unparalleled rate accuracy to customers.”

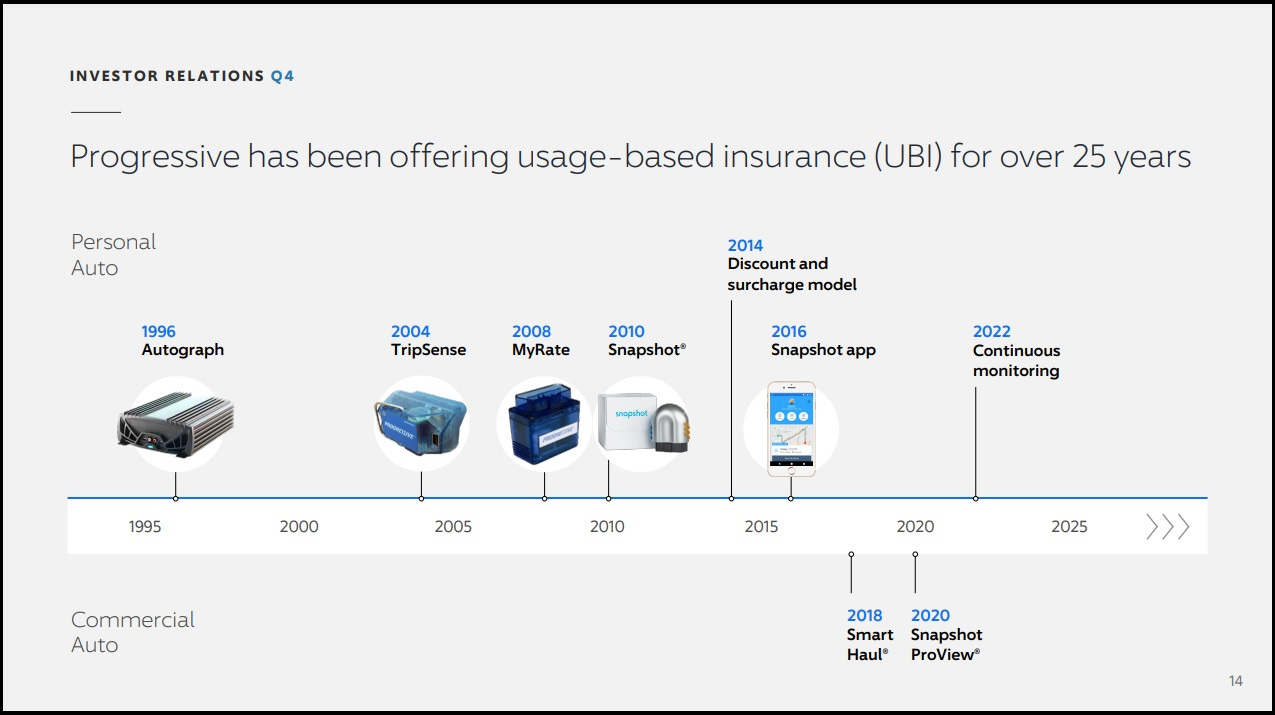

One example of Progressive’s push to maintain that edge, as Griffith discussed in the company’s 2022 shareholder letter, is an update to Snapshot (PGR’s consumer UBI offering); with the new approach, Snapshot will monitor the driver continuously, with policy rates adjusted at each renewal period, as opposed to the prior model where the customer was only required to use Snapshot for a single policy term. (As an aside, note that certain U.S. states, like California, do not allow auto insurers to use telematics / UBI; excluding those states, Progressive management disclosed on its Q1 FY22 call that about 40% of new customers in the direct channel participate in Snapshot.)

As Jain noted, GEICO has woken up; that said, their hesitance over the past 5-10 years gave Progressive a massive head start: GEICO’s comparable UBI offering, DriveEasy, launched in 2019 – nine years after Snapshot.

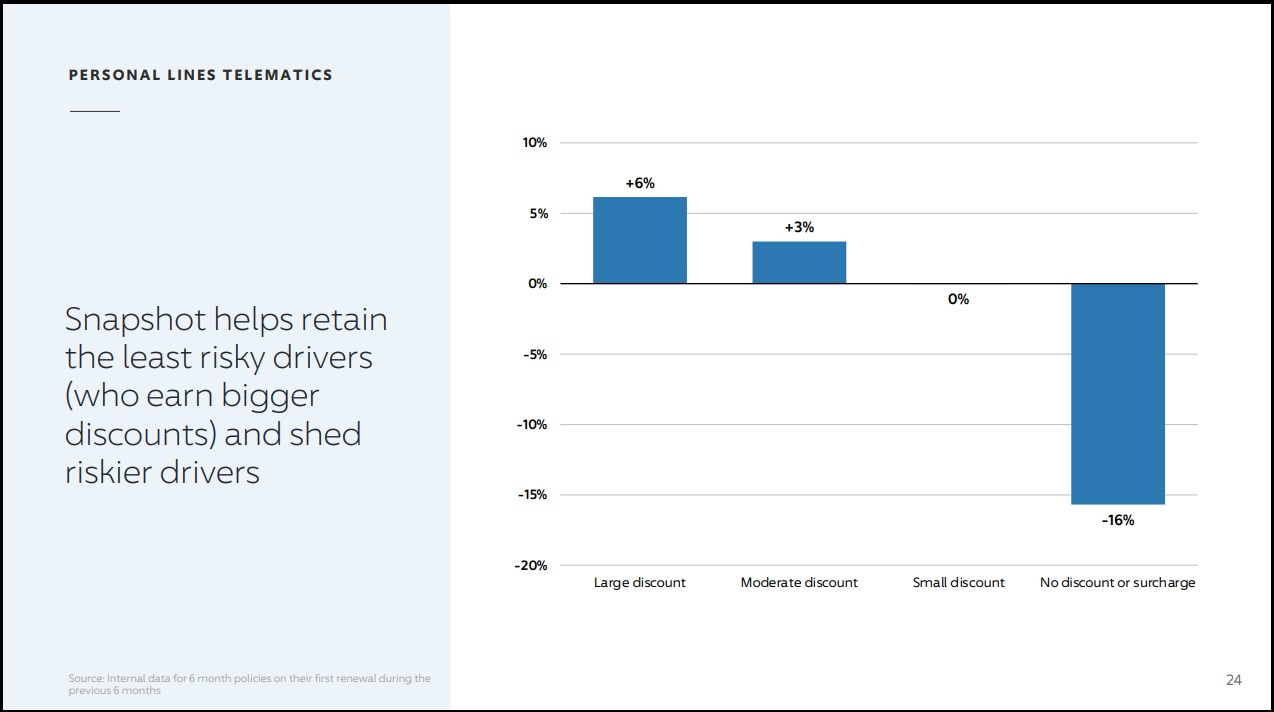

While GEICO was dithering throughout the 2010’s, Progressive was continuously refining Snapshot to match rate to risk. For the past 5+ years, that has included the possibility of a surcharge based on the customer’s driving (today, the maximum potential discount is 45%, while the maximum potential surcharge is 60%). As this quote from Progressive’s Q4 FY22 call highlights, they’ve shed a higher percentage of risky / bad drivers as a result – some of whom likely moved their policy over to GEICO (a customer GEICO may have mispriced the risk on): “Renewal rates for the safest drivers earning the biggest discounts are about 6% higher than average, while they're about 16% lower for the riskiest drivers who aren't receiving a discount… The program systematically helps us retain lower risk drivers and shed higher risk ones.” (This is already a long post, but note that PGR also discussed initiatives underway to use UBI / telematics in pricing new business; if successful, this could be a material tailwind for PIF growth.)

Conclusion

It’s encouraging to hear Berkshire management admit in the past few years that it erred in its assessment on the role of telematics (and has been adjusting accordingly). That said, based on a comparison of their recent results, including a very difficult year for GEICO in 2022, it appears there’s a long way to go before they’ll catch-up with PGR. (“GEICO is severely behind Progressive in using technology in underwriting and claims management.”)

This has been a sobering analysis to work through; Berkshire Hathaway accounts for a large percentage of my investment portfolio, and it’s worrisome to see one of its higher profile businesses performing so poorly (that said, it accounts for a relatively small percentage of the company’s overall earnings power / value). Honestly, I think Buffett should be more forthright in discussing GEICO’s recent struggles; it didn’t receive a single mention in the 2022 shareholder letter, but I suspect shareholders will press him on the topic at the annual meeting. (GEICO CEO Todd Combs: “We are investing in data and technology. We have lots of initiatives going on and they take time.”)

In summary, Progressive took advantage of a strategic misstep by its primary competitor in direct auto insurance; while GEICO still has significant relative competitive advantages in the U.S. auto insurance industry, the company’s performance in recent years shows that even a well-positioned business requires adept managerial decision-making to live up to its full potential.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

Question: I shared your fantastic Markel piece with one person. It occurred to me that I should have contacted you first for permission and/or bought a gift link. In either event, please let me know. Thank you!

I hope that you've shared this with Gregg Warren at Morningstar. GEICO's slow pace of technological adaptation has been one of his publicly stated concerns for years. Your work here is terrific. Full disclosure: Berkshire is by far my largest holding.