A Rebuttal To "Problems At Airbnb"

Note: Today’s post isn’t part of the regular publication schedule.

I’ll be back tomorrow morning with the Tractor Supply deep dive.

On April 6th, The Bear Cave published a research report titled “Problems at Airbnb (ABNB)”. While Edwin Dorsey (the author) makes some reasonable points about the inherent challenges faced in this business, I think his conclusions are misguided. Before jumping in, a quick disclosure: as TSOH Investment Research service subscribers know, I’ve never owned Airbnb. It’s a company I’ve followed for years and would invest in at the right price, but the stars haven’t aligned (yet). With that all out of the way, here’s an overview of The Bear Cave’s thesis (from the introduction of “Problems at Airbnb”):

“An investigation by The Bear Cave has uncovered that amid numerous scandals and horror stories the Airbnb platform has shifted towards professionally managed properties, many of which are now gearing to directly compete against the company. Airbnb’s top professional hosts are building out their own booking platforms and offering cheaper deals to cut out Airbnb, growing their own email lists and distribution, and offering loyalty discounts to book off of Airbnb. In short, Airbnb’s future will look a lot different than its past as the company will now need to compete against its best and largest hosts.”

As it relates to the long-term investment thesis for Airbnb, here are the three arguments made by The Bear Cave that I think deserve further attention:

1) Scandals and horror stories from Airbnb guests / hosts

2) The shift towards professionally managed properties

3) Direct competition from those professional managers

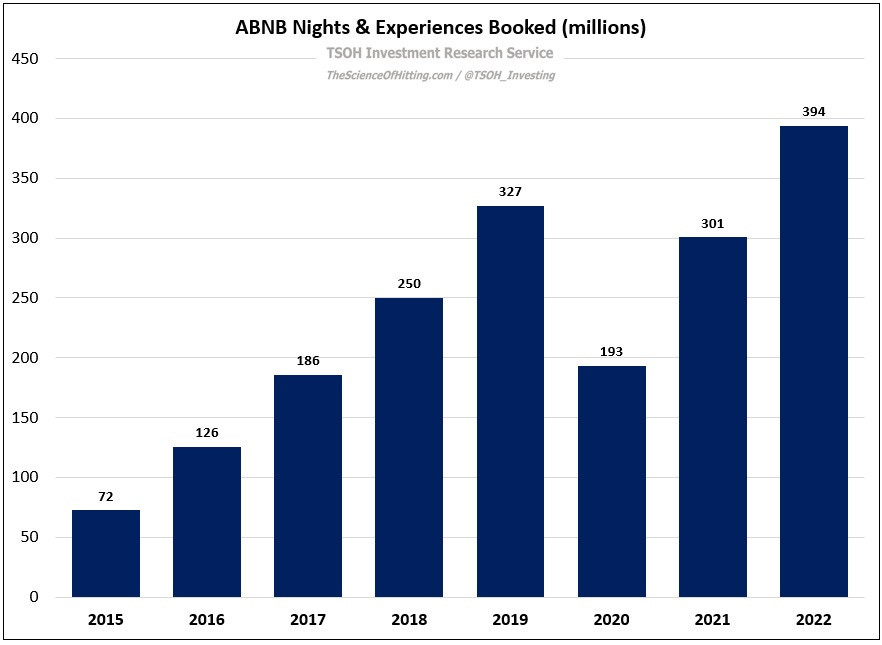

On the first point, there’s no question that Airbnb has dealt with its fair share of “horror stories” over the years. With 394 million nights & experiences booked on the platform in 2022, it’s not surprising that a given percentage of those bookings will be problematic for the guest and / or host. I’m not dismissing these concerns, particularly as it relates to criminal activity - but it is an acknowledgment that this is an inherent risk of this model. That was the case a decade ago (when Airbnb’s booking volumes were significantly lower than current levels), and it will be the case a decade from now. (“We all know you can’t stop everything, it’s all about how you respond; when it happens you have to make it right, and that’s what we try to do each and every time.”)

The scope of that problem is clearly relevant to the discussion. As opposed to relying on anecdotal evidence / news stories, I think it’s more useful to examine the data. As disclosed in Airbnb’s S-1 (filed 11/16/2020), problematic bookings – for the host or the guest – are pretty rare: “For the twelve months ended September 30, 2020, only 0.137% of stays and experiences on Airbnb had a safety-related issue reported by a host or guest. Over that same period, only 0.053% of stays had a significant claim of $500 or higher paid out for property damage under our Host Guarantee.”

The company hasn’t consistently updated these figures over time, but they told Bloomberg in June 2021 that fewer than 0.1% of stays result in a reported safety issue. Unless that has meaningfully changed in the past 22 months, it’s difficult to argue that this problem is becoming more significant (when properly measured relative to Airbnb’s size, not in absolute terms).

Improved outcomes are reinforced by the gamification of the platform (host and guest reviews / ratings, which penalizes bad actors), as well as the operational procedures implemented by Airbnb (identify verification / background checks, fraud and scam prevention services, and the guest refund policy). A notable example of these efforts has been the evolution of AirCover, which was introduced in 2011 as a way to help protect hosts from adverse events - most notably damage to their home (it was introduced in response to a host who had their home trashed by Airbnb guests). Not only has the Host program been improved over time (the original $50,000 damage protection guarantee has been increased to $3 million), but Airbnb has also rolled out a version of AirCover for guests. In summary, I doubt Airbnb would argue with the idea that there’s an inherent risk associated with allowing strangers to share / stay in other people’s homes; over the past 10+ years, they’ve made operational improvements and significant enhancements to its AirCover protections for hosts and guests alike to alleviate those concerns.

The Bear Cave’s second point relates to platform supply mix. Effectively, Edwin argues that the mix of platform volumes has shifted to professional hosts who are keen to take those bookings off platform (to avoid Airbnb’s service fees). Unlike with the safety-related issues, The Bear Cave does quantify the professional host data (citing an April 2022 AirDNA blog post):

“Professional property managers represent 1% of all vacation rental hosts, but manage 23% of available listings which generate 35% of total revenue. The data from AirDNA also shows that professional hosts have been increasing their market share over time.”

As I wrote in my ABNB deep dive (September 2021), individual hosts are very important to the supply equation at Airbnb; it’s the key point of differentiation versus competing alternative accommodations platforms: “Individual host growth is one of my main KPI’s. A large and growing number of individual hosts is what truly makes the platform unique. Notably, the GBV per average listing in 2019 was ~$7,000, which suggests this is a supplemental source of income for many individual hosts. In my mind, that conclusion offers some protection to Airbnb’s unique supply (~70% of listings are only available on Airbnb). Said differently, for the average individual host, as long as they’re seeing activity on Airbnb, it’s not worth the headache to list their properties elsewhere. If that holds, it will be a meaningful long-term competitive advantage for Airbnb. (‘Individual hosts are the core of our community… OTA’s are primarily focused on professional hosts.’)”

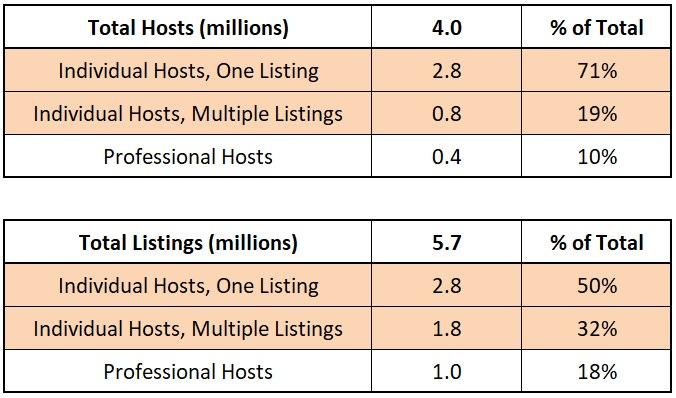

The deep dive included relevant metrics for thinking through this issue (from the S-1: “As of December 31st, 2019, 90% of our hosts were individual hosts, and 79% of those hosts had just a single listing… For individual hosts who had at least one listing in 2019, the average number of listings was 1.3.”). As you can see below, as of yearend 2019, I estimate that professional hosts accounted for ~18% of active listings on Airbnb (~1.0 million listings).

The AirDNA data cited by The Bear Cave suggests that professional hosts now manage ~23% of available listings. On the ~6.6 million active listings reported by Airbnb at yearend 2022, with the total negatively impacted by the decision in May to remove ~150,000 listings in China, that implies individual hosts (the other ~77% of listings) exceed five million listings, up ~10% since yearend 2019. To provide some context for that growth rate, note that the number of total online bookable accommodations available through Vrbo at yearend 2022 – roughly two million – was lower than at yearend 2019.

The large difference in active listings between these two platforms, which has widened further over the past few years, speaks to the challenge for Airbnb’s competitors. There’s value for guests in the long tail, especially depending on where you’re searching geographically and the specific requirements of the property - and Airbnb is the clear leader among this unique supply.

Airbnb has innovated to ensure a smoother onboarding experience for new hosts, and they have the guests (demand) to help new host get their “business” off the ground: as noted at a September 2022 conference, ~50% of new hosts get a booking within three days and ~75% get a booking within eight days (in 2019, those figures were four days and 16 days, respectively).

While professional hosts are an important part of the equation, they are unlikely to be unique / differentiated supply; as The Bear Cave correctly notes, they have good reason to list on other platforms (like Vrbo), in addition to an economic interest in driving guests directly to their own website. That thinking is unlikely to apply to your average individual host, who may make ~$10,000 a year from their Airbnb listing (supplemental income). The task for Airbnb, as has been the case for years, is to be the first destination that new hosts think of when they consider listing their home (and to stay listed there). Given that nearly 40% of new hosts in Q4 FY22 started out as Airbnb guests, this is another example of why Airbnb’s unrivaled scale in alternative accommodations – for guests and hosts alike - is a competitive advantage.

There’s one caveat to this discussion. In The Bear Cave post, Edwin quoted the following from AirDNA: “Professional property managers represent 1% of all vacation rental hosts, but manage 23% of available listings which generate 35% of total revenue.” If you go to the blog post (here), you’ll see that this was pulled from the article summary on the right hand side of the page. By comparison, here’s the quote from the actual article (bold added for emphasis): “Professional property managers only represent 1% of all Airbnb and Vrbo hosts, but they manage 23% of available listings which generate 28% of total revenue.” (I have no idea why AirDNA has two different revenue estimates in the same article). The first quote, from The Bear Cave article, seemed to suggest this was the mix at Airbnb; however, the second quote states that this figure applies to Airbnb and Vrbo. Without getting into assumptions about their respective business mix – which is futile anyways given how little information Expedia has shared about Vrbo’s results over the years - the point is that there’s reason to be a bit skeptical about the claim that ~23% of Airbnb’s listings are from professional hosts. On a related point, you should also note that AirDNA is citing domestic data; Airbnb is a global business, with non-U.S. markets accounting for >50% of its 2022 revenues.

The final argument from The Bear Cave relates to the incentives of professional hosts. The point here is straightforward: if they can convince guests to come to their listings directly, all else equal, they can make more money and / or pass-through savings to guests (to quantity that opportunity, Airbnb’s 2022 revenues were equal to ~13% of gross booking value, or GBV).

We have a clear comp for this competitive dynamic: the major hotel chains and online travel agencies, or OTA’s. The major difference between these two examples is that a handful of hotel chains control a significant share of available U.S. rooms and have well-known brands, large marketing budgets, consumer loyalty programs, etc., while the leading suppliers (property managers) in alternative accommodations hold an infinitesimal share of the market and are unknown brands to the vast majority of customers. (And as AirDNA’s data shows, suppliers with multiple properties / listings have much worse average guest ratings than individual hosts; while The Bear Cave argues professional property managers typically offer “a better guest experience”, that conclusion is not supported by AirDNA’s ratings data.)

That doesn’t invalidate Edwin’s broader point: if you travel to the same place every year and find a property you enjoy staying at, Airbnb has no ability to impede you from booking with that supplier directly. That said, this was true five years ago and will be true five years from now (despite this, as shown earlier, Nights & Experiences booked on Airbnb have increased ~5x since 2015). There will always be a certain percentage of guests who will price shop or book directly when looking at alternative accommodations, just like they do when booking a hotel room or a flight. (As it relates to The Bear Cave’s first point on safety-related issues, these customers will no longer have the protections offered through AirCover; in addition, if a guest books directly with a smaller operator that goes belly up, they will be exposed to counterparty risk.) Based on the company’s financial results over the past 5+ years, I think there’s compelling evidence that a large number of consumers will default to booking their trip through Airbnb; that argument may become even stronger if Airbnb rolls out a loyalty program. (The recent struggles at Vacasa, a leader in vacation rental management, are also noteworthy.)

Conclusion

As with any company, Airbnb is far from perfect. Its current category leadership cannot be taken for granted; defending that position demands constant improvements to the guest and host value proposition on the platform. In my opinion, initiatives like AirCover, Categories, and I’m Flexible are reinforcing Airbnb’s leadership position in the alternative accommodations category (while leveraging its dominant scale in supply and demand).

As noted at the outset, Edwin believes Airbnb’s future will look quite different (worse) than its past. My view, as I’ve told TSOH subscribers since the deep dive was published, is that this is a high-quality business with a bright future (in the interim, it would be hard to argue the financial results have been anything less than stellar). We’ll see how it plays out over the coming years.

Even though I disagree with his conclusions, I want to thank Edwin for sharing his research; I spoke with him before writing this, and he was happy to hear an alternative perspective (and to have it shared publicly). I respect his willingness to remain open-minded to views that differ from his own.

NOTE - This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved. The TSOH Investment Research Service is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.